NOTE TO THE READER

The Five Pillars of ikigai

T hroughout this book, I refer to the Five Pillars of ikigai. They are:

Pillar 1: Starting small

Pillar 2: Releasing yourself

Pillar 3: Harmony and sustainability

Pillar 4: The joy of small things

Pillar 5: Being in the here and now

These pillars come up frequently, because each one provides the supportive frameworkthe very foundationsthat allows ikigai to flourish. They are not mutually exclusive or exhaustive, nor do they have a particular order or hierarchy. But they are vital to our understanding of ikigai, and will provide guidance as you digest what you read in the forthcoming pages and reflect on your own life. Each time they will come back to you with a renewed and deepened sense of significance.

I hope you enjoy this journey of exploration.

CHAPTER 1

What is ikigai?

W hen President Barack Obama made his official visit to Japan in the spring of 2014, it befell Japanese government officials to choose a venue for the welcome dinner to be hosted by the prime minister of Japan. The occasion was to be a private affair, preceding the state visit that was due to start officially the following day, and which included a ceremonial dinner at the Imperial Palace, with the emperor and empress presiding.

Imagine how much consideration went into the choice of restaurant. When it was finally announced that the venue was to be Sukiyabashi Jiro, arguably one of the worlds most famous and respected sushi restaurants, the decision was met with universal approval. Indeed, you could tell how much President Obama himself enjoyed the experience of dining there from the smile on his face when he stepped out. Reportedly, Obama said it was the best sushi he had ever eaten. That was a huge compliment coming from someone who grew up in Hawaii, with exposure to a strong Japanese influence including sushi, and who, presumably, had had many previous experiences of haute cuisine.

Sukiyabashi Jiro is proudly headed by Jiro Ono, who is, as I write this, the worlds oldest living three-Michelin-star chef, at the age of ninety-two. Sukiyabashi Jiro was already famous among Japanese connoisseurs before the first Michelin Guide for Tokyo in 2012, but that publication definitely put the restaurant on the world gourmet map.

Although the sushi he produces is shrouded in an almost mystic aura, Onos cooking is based on practical and resourceful techniques. For example, he developed a special procedure for providing salmon roe (ikura) in a fresh condition throughout the year. This challenged the long-held professional wisdom followed in the best sushi restaurantsthat ikura should only be served during its prime season, the autumn, when the salmon brave the rivers to lay their eggs. He also invented a special procedure in which a certain type of fish meat is smoked with burned rice straw to produce a special flavor. The timing of the placing of the sushi plates in front of eagerly waiting guests must be precisely calculated, as must the temperature of the fish meat, in order to optimize the sushis taste. (It is assumed that the customer will put the food in his mouth without too much delay.) In fact, dining at Sukiyabashi Jiro is like experiencing an exquisite ballet, choreographed from behind the counter by a dignified and respected master with an austere demeanor (although his face will, by the way, crack into a smile from time to time, if you are lucky).

You can take it that Onos incredible success is due to exceptional talent, sheer determination, and dogged perseverance over years of hard work, as well as a relentless pursuit of culinary techniques and presentation of the highest quality. Needless to say, Ono has achieved all of this.

However, more than that and perhaps above all else, Ono has ikigai. It is no exaggeration to say that he owes his incredibly fabulous success in the professional and private realms of his life to the refinement of this most Japanese ethos.

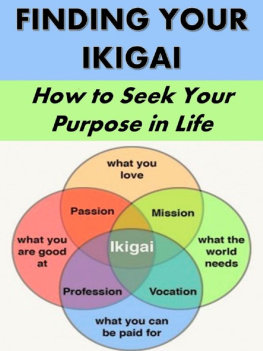

Ikigai is a Japanese word for describing the pleasures and meanings of life. The word literally consists of iki (to live) and gai (reason).

In the Japanese language, ikigai is used in various contexts, and can apply to small everyday things as well as to big goals and achievements. It is such a common word that people use it in daily life quite casually, without being aware of its having any special significance. Most importantly, ikigai is possible without your necessarily being successful in your professional life. In this sense, it is a very democratic concept, steeped in a celebration of the diversity of life. It is true that having ikigai can result in success, but success is not a requisite condition for having ikigai. It is open to every one of us.

For an owner of a successful sushi restaurant such as Jiro Ono, being offered a compliment from the president of the United States is a source of ikigai. To be recognized as the worlds oldest Michelin three-star chef certainly counts as a rather nice piece of ikigai. However, ikigai is not limited to these domains of worldly recognition and acclaim. Ono might find ikigai simply in serving the best tuna to a smiling customer or in feeling the refreshing chill of the early morning air, as he gets up and prepares to go to the Tsukiji fish market. Ono might even find ikigai in the cup of coffee he sips before starting each day, or in a ray of sunshine coming through the leaves of a tree as he walks to his restaurant in central Tokyo.

Ono once mentioned that he wishes to die while making sushi. It clearly gives him a deep sense of ikigai, despite the fact that it requires many small steps that are in themselves monotonous and time-consuming. In order to make the octopus meat soft and tasty, for example, Ono has to massage the cephalopod mollusk for one hour. Preparing Kohada, a small shiny fish considered to be the king of sushi, also needs much attention, involving the removal of the fishs scales and intestines, and a precisely balanced marinade using salt and vinegar. Perhaps my last sushi making would be Kohada, he said.

* * *

Ikigai resides in the realm of small things. The morning air, the cup of coffee, the ray of sunshine, the massaging of octopus meat and the American presidents praise are on equal footing. Only those who can recognize the richness of this whole spectrum really appreciate and enjoy it.

This is an important lesson of ikigai. In a world where our value as people and our own sense of self-worth is determined primarily by our success, many people are under unnecessary pressure. You might feel that any value system you have is only worthy and justified if it translates into concrete achievementsa promotion, for example, or a lucrative investment.

Well, relax! You can have ikigai, a value to live by, without necessarily having to prove yourself in that way. That is not to say that it will come easily. I sometimes have to remind myself of this truth, even though I was born and grew up in a country where ikigai is more or less an assumed knowledge. In a TED talk titled How to live to be 100+, American writer Dan Buettner discussed ikigai specifically as an ethos for good health and longevity. At the time of writing, Buettners talk has been viewed more than three million times. Buettner explains the traits of the life styles of five places in the world where people live longer. Each blue zone, as Buettner terms these areas, has its own culture and traditions that contribute to longevity. The zones are Okinawa in Japan; Sardinia in Italy; Nicoya in Costa Rica; Icaria in Greece; and among the Seventh-day Adventists in Loma Linda, California. Of all these blue zones, the Okinawans enjoy the highest life expectancy.