Contents

Guide

To my dear husband,

Our life together is my ikigai and will always be an adventure.

Contents

How to use this ebook

Select one of the chapters from the and you will be taken straight to that chapter.

Look out for linked text (which is blue) throughout the ebook that you can select to help you navigate between related sections.

You can double tap images to increase their size. To return to the original view, just tap the cross in the top left-hand corner of the screen.

Introduction: Ikigai

What is ikigai? In more than seven years working as a freelance journalist, this has been the most complex subject I have had to explore to date. Until I was commissioned to write an article on ikigai for the BBC, I took the concept for granted. It is such a common notion and so deeply engraved in the Japanese psyche that I never really stopped and thought about what it means.

The Japanese word ikigai is formed of two Japanese characters, or kanji: iki [], meaning life, and gai [], meaning value or worth. Ikigai, then, is the value of life, or happiness in life. Put simply, its the reason you get up in the morning.

Some recent Western interpretations of ikigai may seem to explore the idea of finding a meaning to your life as a whole, but that is not quite what the word means. The English word life carries the sense of both lifetime and daily life, but in Japanese, we have a separate word for each: the former is expressed by jinsei [], while seikatsu [] denotes everyday life. When I spoke to Akihiro Hasegawa, a clinical psychologist and associate professor at Toyo Eiwa University who has studied the concept of ikigai for years, he made an interesting point. Ikigai translated into English as lifes purpose sounds quite formidable, but ikigai need not be the one overriding purpose of a persons life. In fact, the word life used here aligns more with seikatsu daily life. In other words, ikigai can be about the joy a person finds in living day-to-day, without which their life as a whole would not be a happy one.

The reason the topic of ikigai is a difficult one to tackle even for someone who is Japanese is because, although it is a common concept in Japan, it is not something you learn from a textbook. Growing up and living in Japan for most of my life, I dont recall ever being taught about ikigai in a classroom. Japanese children learn more than 1,000 kanji in elementary (primary) school alone, but ikigai is not one of them. Ikigai is a multifaceted concept that we come to understand as we live life and grow older. What is your ikigai? is not a straightforward question with one right answer but an abstract one, to which an infinite number of responses are possible. Whatever gets you up in the morning is your ikigai and no one can tell you otherwise.

Since there are no ikigai teachers, I undertook my own exploration on the concept, which I share with you in this book. In the coming chapters, we will explore what ikigai means, how to discover your own ikigai, and how doing so can help to bring focus and joy to your life. I am grateful to the experts in different fields who have provided me with their insights, as well as to the people who have shared their ikigai with me (see for some inspiring stories). Everyones ikigai is different, but my hope is that reading about other peoples stories will help you to discover your own.

Life will always come at you with its own set of difficulties and ikigai is by no means a magic formula that makes things perfect. But by having ikigai at each stage in our lives, hopefully we can look back at our life as a whole and feel content. I hope that my search to better grasp the Japanese notion of ikigai will help you not only to understand it, too, but also and more importantly will inspire you to think about your own ikigai. Thank you for joining me on this journey. Whatever ikigai you may find at the end of this book, I say kanpai (cheers) to that!

What is ikigai?

It might be the sound of our alarm clock that forces us awake in the morning, but its the joy we anticipate in the day ahead that gets us up and going. As I explained in the introduction, the word ikigai comes from iki, meaning life, and gai, meaning value. So it can be interpreted as the values in your life that make it worth living.

According to Professor Hasegawa, the word ikigai can be traced back to the Heian period (7941185 CE). Gai comes from the word kai, which means shell, as shells were once regarded as highly valuable. From there, ikigai is derived as a word that means value in living or values in life. There are other Japanese concepts that represent different values, all ending with gai. For example, hatarakigai refers to value in work (hataraki or hataraku means work or to work), while yarigai refers to value in what you are doing (yari or yaru means to do). Ikigai, however, is more of a comprehensive concept.

Because it is related to everyday life, as I explained in the introduction, ikigai tends to be pragmatic rather than simply idealistic. A persons ikigai might be their family, work or hobby, a photography trip they have planned for the weekend, or even something as simple as a cup of morning coffee enjoyed with their spouse, or taking their dog out for a walk.

The Japanese proverb jnin toiro literally means ten people, ten colours: as people are different in their characters, preferences and the way they think, it is only to be expected that ten different people would choose ten different colours when asked which is their favourite. The same is true of ikigai as well. Each persons ikigai is unique because we all find joy in different aspects of life. There is no right or wrong answer.

Work or pleasure?

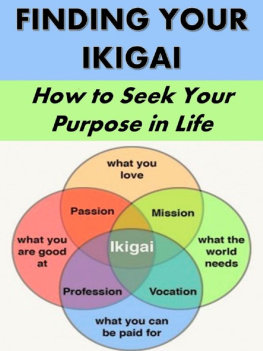

A common Western misconception of ikigai is that it must be related to your career. Those of you familiar with the concept may have seen explanations of ikigai that make use of a Venn diagram consisting of four overlapping circles what you love, what you are good at, what the world needs and what you can be paid for with ikigai at the intersection of all four. I first discovered this definition when I was researching ikigai for my article for the BBC and it took me by surprise.