www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2016 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2016

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

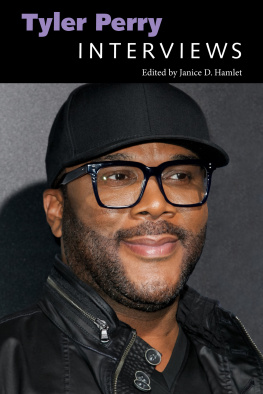

Names: Russworm, TreaAndrea M., editor. | Sheppard, Samantha N., editor. | Bowdre, Karen M., editor.

Title: From Madea to media mogul : theorizing Tyler Perry / edited by TreaAndrea M. Russworm, Samantha N. Sheppard, and Karen M. Bowdre ; foreword by Eric Pierson.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2016. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015048409 (print) | LCCN 2015049985 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496807045 (hardback) | ISBN 9781496807052 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496807069 (epub institutional) | ISBN 9781496807076 (pdf single) | ISBN 9781496807083 (pdf institutional)

Subjects: LCSH: Perry, TylerCriticism and interpretation. | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Media Studies. | PERFORMING ARTS / Film & Video / History & Criticism. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / African American Studies.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.P4575 F86 2016 (print) | LCC PN1998.3.P4575 (ebook) | DDC 791.4302/8092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015048409

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Foreword

We all have a Madea in our families. She is sometimes the crazy aunt with no filter who often says the first thing that comes into her head. She is the loudest and most uninhibited person in the room. A matriarch, Madea is an important element of Black life. With his plays, films, and television shows, Tyler Perry has taken what for some is a sacred cultural figure and shared it with mainstream America. In many ways, Perrys popular, politically incorrect character is viewed as all that is wrong with Black women in America. Loud, opinionated, and unapologetic about her behavior, Madea can all too easily be viewed as a stereotype. Because Hollywood films offer so very few alternatives to representation of Black women and Black life on screen, Perrys Madea and the films she appears in are often discussed without much context.

This collection will help provide readers with a rich context through which they can engage Madea and the other characters in Perrys world. The editors of this collection have done a significant service to the scholarly community in pulling together these multiple perspectives on the work and impact of Perry. The collection is not just a reflection on the significance of Perry; it is also a reflection of the complexity of questions regarding the experiences of Black folks in a world that has become increasingly influenced, manufactured, and marketed by and through the media. Normally, these essays would be spread across a series of journals and conference presentations, their relevance and importance limited to those venues.

Perrys cultural productions allow scholars from a range of disciplines and theoretical models to offer valuable contributions. Cultural Studies, Critical Race Theory, Political Economy, Film Theory, Ideological Criticism, and Rhetoric are among the available mechanisms and methods for engaging his work. Through the process of engaging Perry, these scholars have created a critical framework for examining the past and the future of racial discourse in American national and popular culture. Significantly, the analyses shared here are not just about Perry, though he is a worthy figure of critique in and of himself. The essays are also about the relationship between Black people and the social and cultural institutions that manufacture and circulate images of blackness.

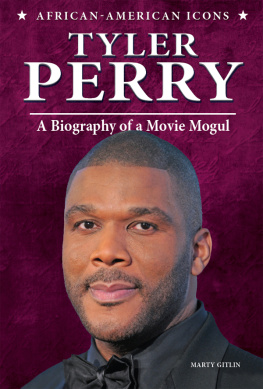

I have often questioned how I could possibly take the creator of Madea as a serious voice in the media industry. Prior to his work as executive producer of Precious (Lee Daniels, 2009), Perry had only come on my radar when the latest iteration of Madea Goes... would hit the theatre. I treated his Madea films much like I treated the Ernest Goes... comedies: as a cinematic waste of time. With the release of Precious, however, I began to take a more serious look at the work of Perry and began to consider some of the problems and possibilities of his media empire. What became clear to me then, and has crystallized since 2009, is that Perry is a media force who is worthy of critical engagement because of his polarizing productions.

Perrys influence on Black film and media has not always been so visible, though he has clearly labored over the years to solidify his place within the media industry. For the last decade, Perry has been the dominant manufacturer of popular Black images. As America consumes these, at times, troubling images, Perry remains unapologetic to those who have issues with his offerings. In this regard, the control of the images of Black experiences have been contested spaces beginning with D. W. Griffiths The Birth of a Nation (1915), through the debates centering on the television version of Amos n Andy (CBS, 195153) in the 1950s, then moving though the era of Blaxploitation in the 1970s, and now through the work of Perry. However, what makes the work of Perry different than the others mentioned is that he is African American and there are different expectations in this era. When whites get the Black experience wrong, we can see the ways in which roles are played by the economics and lack of cultural understandings. Perry, rightly or wrongly, will be and is held to a different set of standards. Is Perry the voice of the Black experience or is he just a businessman trafficking in the experience for profit?

In attempting to answer questions like these, it is important that we understand Perrys transition from theatre writer/actor/producer to that of multimedia mogul. During his time in the Black theatre, Perry not only honed his craft but also created a foundational relationship with his target Black audience, which became the base for his future success. Perrys theatre experience reminds us of the vitality of the Black theatrical experience. While so much of the power of Black theatre has been absorbed into the mainstream marketplace, it is easy to forget the power of theatre as a transmitter of Black culture. Importantly, the space of the Black theatre was also apart from the critique of the mainstream. In that space, Perry was free to have conversations regarding the ways in which race, class, and gender impact the Black experience with an audience that was almost always exclusively Black. These dialogues allowed for frank discussion in a safe space, analogous to the sanctuary of the Black church.

It is Perrys use of the Black church as both a setting and as a cinematic trope that causes me the greatest concern and is one of the other major problems with his representations. The Black church has always been an important and significant institution to the Black community. The power of the Black church was truly on display during the civil rights movement; it became the place where many of the leaders of the period began their sphere of influence. It has been one of the few historical places were Blacks have felt that they were safe and that they could truly express themselves. It was a site of refuge, a place where Blacks could often meet and share their most intimate feelings and fears. In much of his work, Perry has opened up the church so that others can look inside. The outing of Black folks and a cherished institution in the name of commerce is one reason so many seem to resist and resent Perrys work.