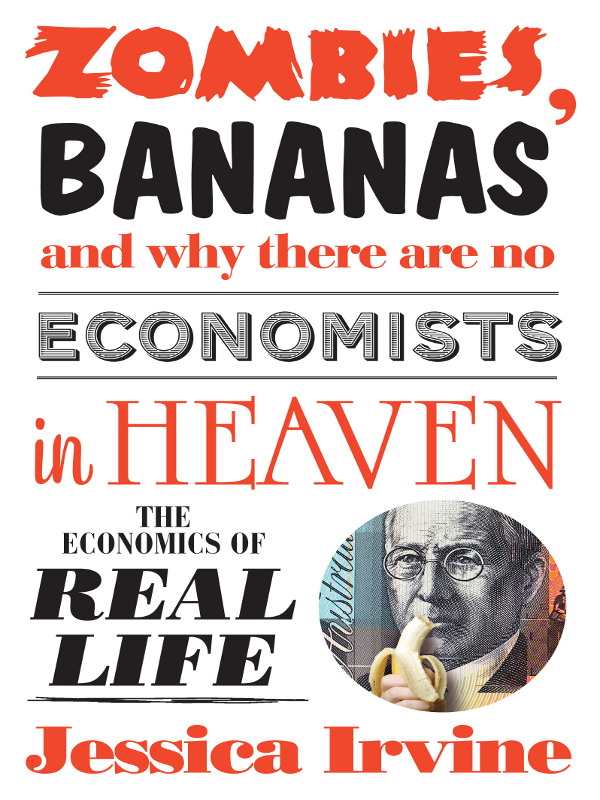

First published in 2012

Copyright Jessica Irvine 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Fairfax Books, an imprint of

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 997 5

Internal design by Design by Committee

Set in 10.75/16.5 Electra by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Ashley

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Why there are no economists in heaven

CHAPTER 1

Yes, we have no bananas

CHAPTER 2

A few home truths

CHAPTER 3

Can economics make you skinny?

CHAPTER 4

The economics of love

Why economists make miserable Christmas

gift givers

CHAPTER 5

Yours irrationally

CHAPTER 6

A helping hand for the invisible hand

CHAPTER 7

Bottom lines and other taxing matters

CHAPTER 8

Political tantrums and tiaras

CHAPTER 9

Zombies, NINJAs and the GFC

CHAPTER 10

The Aussie economy

What follows is a curated collection of some of my Irvine Index columns from the Saturday News Review section of the Sydney Morning Herald. The numbers that appear with each column were the most up to date available at the time of original publication. I did think about trying to update them all for this book, but many come from Australian Bureau of Statistics surveys that are updated every month or quarter. And you know what? Life is short. More on that later...

Each column has a sources list with concise details about which websites, publications or reports the numbers are drawn from. If youre searching for a specific figure and you cant find it, email me at jirvine@smh.com.au or tweet @Jess_Irvine and Ill try to help out. You can also get in touch through my personal blog, econogirl.com.au.

Enjoy.

Why there are

no economists

in heaven

All we have to decide is what to dowith the time that is given to us.

The wizard Gandalf, The Lord of the Rings:The Fellowship of the Ring, 2001

We are all going to die. Not todayfingers crossedand probably not tomorrow either. But soon, sooner than you think, we are going to die. Sorry to be so melodramatic about it, but its kind of important. I admit I have an ulterior motive in mentioning this fact just now: I seek to ward off in you that powerful feeling of sleepiness that usually accompanies the act of picking up a book about economics. I know that deep down you know that economics is importantthats why you bought this book. But its true, economics can come across as pretty boring. It is a singular achievement of the economics profession that it has managed to make the study of our daily lives and interactions about as exciting as a maths quiz.

Which is probably unfair on a lot of economists. There has been something of a renaissance in economic writing lately; econo-curious types can access an entirely new industry of economic books and websites, the fundamental premise of which seems to be that if you add the suffix onomics, you can make anything interesting. Witness Freakonomics, Parentonomics, Spousonomics, Newsonomics, Boganomics and, I kid you not, Beeronomics (which is presumably a subset of Boganomics). And as a marketing trick, it works. Why? Because the stuff that economists have to say is interesting. It goes to the heart of who we are and why we do the things we do. Stripped of all the boring equations, hideously complex graphs and other hieroglyphics economists use to communicate, obfuscate and generally big-note themselves, economics is about one thing and one thing only: maximising societys total stock of wellbeing, and well, what could be more important than that?

Ive been writing about economics for the Sydney MorningHerald for the better part of a decade and have come to regard the job of economics journalist as similar to that of a foreign correspondent. Okay, the most exciting posting youre ever likely to get is to Canberra (been there, done that). And instead of enjoying lavish dinners at ambassadors residences you get party pies in the federal budget lock-up (for a full menu, turn to Chapter 7 and The inside scoop on the budget lock-up). And despite the foreign language spoken by many of your economist contacts (NAIRU or GDP deflator, anyone?) you get no budget to hire a translator. The skill of the economics journalist lies in letting yourself go native for a while, learning the language and cultural norms of your subjects, and then translating it all back into English for an interested public. If economists ever learn to speak plain English, Ill be out of a job. But its not a prospect I lie awake at night worrying about.

So, what was I talking about? Oh yeah, death. There are very few things that matter more to an economist than the idea of scarcity, both of timedid I mention we are all going to die?and of resources, including land, physical capital and labour. When it comes down to it, economists owe their entire existence to the presence of scarcity.

To see why, try to imagine a world without scarcitya world where time, money and all things exist in never-ending abundance. Everything would be free. We wouldnt need jobs because we wouldnt need income. Fancy spending the entire day in your undies, slumped on the couch watching The Bold and the Beautiful? No worries, time is endless, so you may as well. Rather spend the day picking diamonds off that diamond tree in your backyard? Go for it. But then again, why bother? Diamonds are free and youre dripping in them. In this world of limitless resources, if you want for anythinga coffee, a book, a microwave, a boatyou can simply press a button and that object will magically appear in your living room. All you have to do is relax in your waterfront mansion and enjoy the view, because, of course, someone has invented a space compressor that means you can open any door in your house and be where you want to be; open any window and see what you want.

No time. No space. No money. You want for nothing. You never die. Youre never lonely, because no one you have ever loved has ever died. You can do whatever you want, whenever you want, without any regard for your mortality. The need to settle down, have kids, get a job, get a mortgage? Gone. We could be young forever. To me, it sounds pretty much like every vision of heaven ever dreamed up by any religion. Endless. Abundant. Free.

Next page