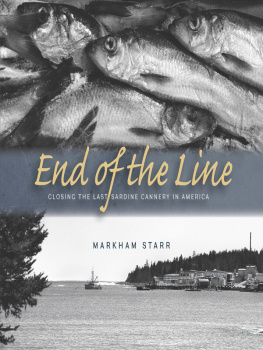

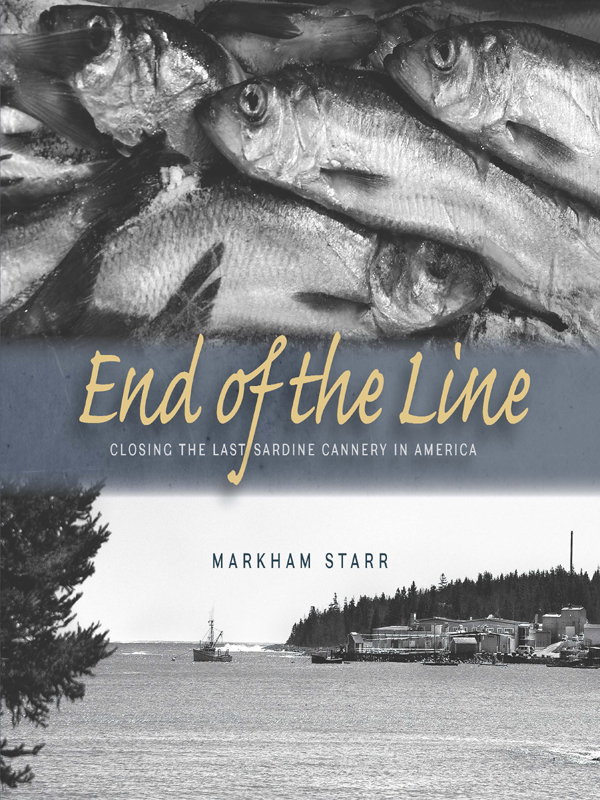

End of the Line

A Driftless Connecticut Series Book

This book is a 2013 selection in the Driftless Connecticut Series, for an outstanding book in any field on a Connecticut topic or written by a Connecticut author.

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Middletown CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2013 Markham Starr

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed and typeset in Ludwig by Eric M. Brooks

The Driftless Connecticut Series is funded by the BEATRICE FOX AUERBACH FOUNDATION FUND at the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving.

Starr, Markham.

End of the line: closing the last sardine cannery in America / Markham Starr.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-8195-7345-2 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8195-7346-9 (ebook)

1. Stinson Seafood History. 2. Fish canneries Maine History. 3. Canned sardines Maine History. 4. Canned fish industry

Maine History. I. Title.

HD9459.S75S73 2013

338.766494 dc23 2012030736

5 4 3 2 1

For all those who once worked at Stinson Seafood

Contents

Preface

ix

END OF THE LINE

A Typical Day at the Plant, As Described by Peter Colson

Final Impressions

Acknowledgments

Preface

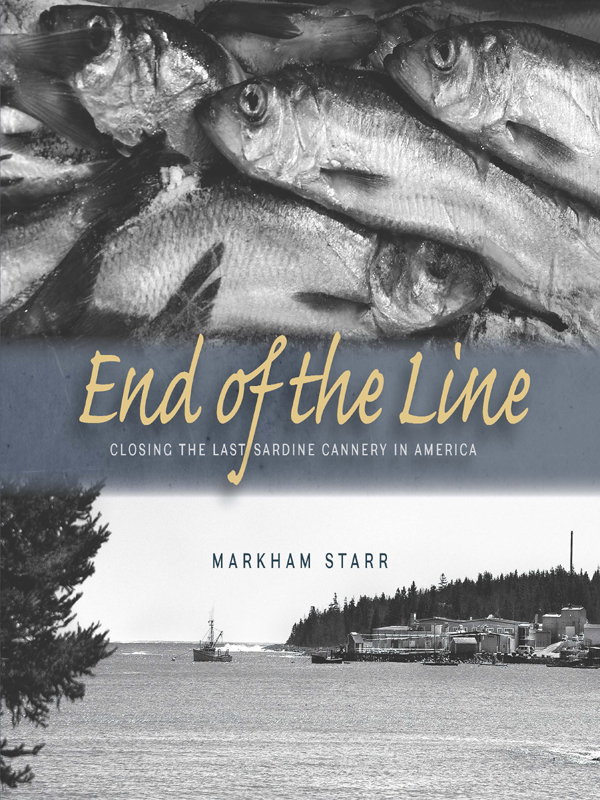

I FIRST HEARD OF STINSON SEAFOOD, in the Maine village of Prospect Harbor, shortly before its closing was announced on my local public radio station. After thinking about the 128 people who would soon lose their jobs in the perpetually depressed economy of Down East Maine, I began to wonder what this particular closing meant to the history of Gouldsboro, the town that had housed this business since its inception nearly 100 years ago. Although the closing of yet another factory has become an all-too-common event in small-town America, it might not have garnered much attention beyond Gouldsboros borders except for one unusual fact: Stinsons was the last sardine cannery operating in the United States. Its passing would represent the final chapter of what had once been a vibrant enterprise along the entire Maine coastline. This was not simply another case of Americas glory now faded, but instead, the complete obliteration of that past. In this particular closing, I couldnt help but see a reflection of the broader situation in our country.

The history of the Stinson Seafood Company parallels the history of American industry. Purchased by Cal Stinson with a partner in 1927, the business prospered and grew for many decades. What many American consumers think of as sardines are really herring, a silvery fish that migrates in huge schools along the Atlantic coast. To minimize the time required to get these tasty fish into cans, Stinson built new plants along their migratory pathway. As the business grew, employing ever-greater numbers of workers, the company also added its own fleet of herring boats to ensure delivery of the basic raw materials. Eventually, even the cans themselves would be manufactured on-site. In the second half of the twentieth century, Stinson embodied the typical American success story. Begun with little more than pluck and a strong work ethic, Stinson now exported their products around the world and employed nearly 1,200 workers. These employees were as devoted to the company as the company was to them, many remaining for years at the same plant. All of this, however, would soon change.

A new concept would alter the American workplace forever: globalization. By the 1990s, the world had begun to shrink at an ever-increasing pace with a corresponding reduction in the loyalty shown by major corporations to the workers who built them. If new workers could be found elsewhere people who would work for lower wages a company could simply move the factory to them, leaving an entire community behind. Fueled by corporate takeovers that emphasized profitability, industrial plants around the country fell prey to this trend. Factories were often stripped of their most valuable assets before the remains were moved offshore. Over the last ten years of the twentieth century, more than 40,000 factories closed in the United States. Iconic American products such as Converse sneakers, Rawlings baseballs, and Levis jeans which, like Stinsons sardines, had been manufactured in this country for many decades suddenly became imports. Ironically, even the quintessentially American board game Monopoly is no longer made in the United States. The real face behind this new American economy greed was briefly revealed during the collapse of 2008. However, once the initial hand-wringing ended, little changed, either in government regulation or corporate culture. Business continues as usual.

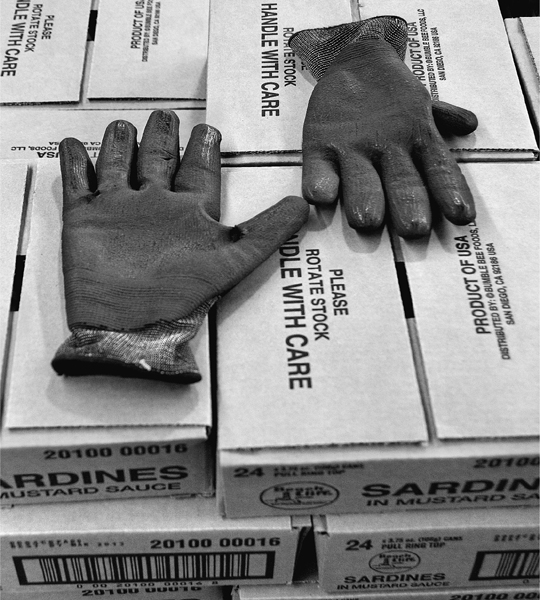

Family ownership of Stinson ended in 1990, signaling, perhaps, the beginning of the end. Over sixty years of ties between company owners and local families vanished. Individual canneries along the Maine coastline began to disappear, one after another, as larger corporations bought, stripped, and closed them to reduce competition. Stinson Seafood changed hands several times before eventually being bought by Bumble Bee Foods. In 2004, Bumble Bee and Connors Brothers of Canada signed an agreement to combine. As Connors controls the largest share of the canned sardine industry, it was but a matter of time before the Prospect Harbor plant also would shut down; it was simply good business. A month after the closing, the cannerys equipment would be sent to New Brunswick. An era would end. The American tale of rags to riches now ends with a modern twist: from rags to riches to another country.

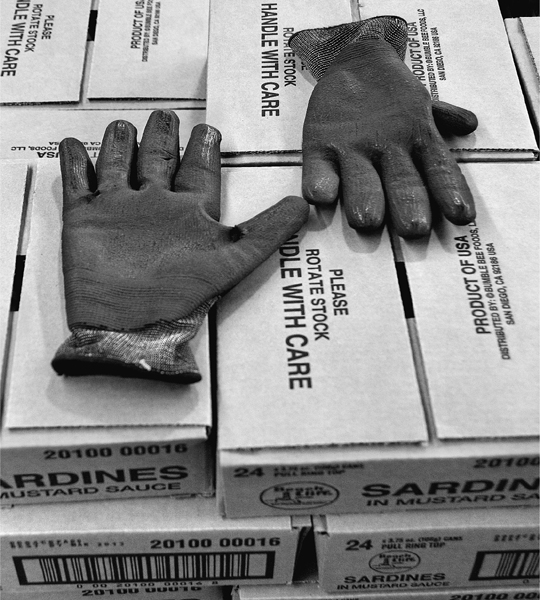

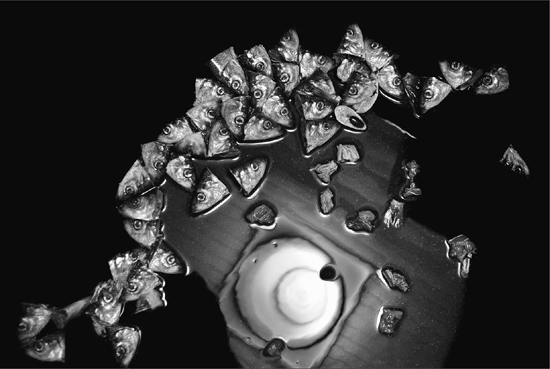

Because I felt that what was happening in Prospect Harbor was a reflection of what was occurring around the country, I approached Bumble Bee to ask if it would be possible to photograph the canning process, as well as the people who were still working at the plant, before the line was shut down forever. It would be the last chance to document an American sardine cannery in operation. Perhaps recognizing the historical importance of this moment, Bumble Bee agreed to allow a few people to record the inner workings of the factory. I traveled to Maine in March 2010, approximately one month before the cannery closed, to photograph it in operation over the course of a day and a half. We were allowed complete access to the plant, but asked not to bother the workers as the company needed to finish canning its stockpile of frozen fish. Those workers, feeling the stress of losing the jobs they had held for so long, did not need the additional burden of having to discuss it with us. These instructions, combined with the seven-hour drive from my home to Prospect Harbor, would prevent me from gathering much personal information about the workers; I had to be satisfied simply with photographing them as much as possible.

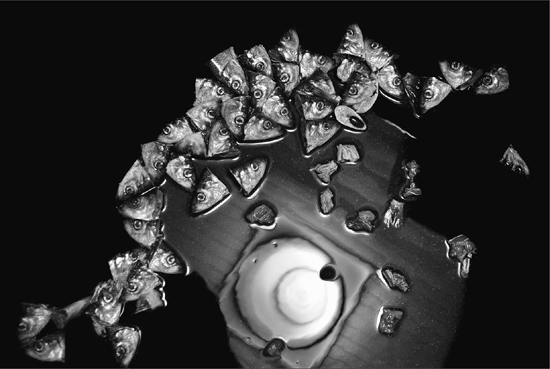

While I was most interested in the people who worked at the factory, my secondary goal was to record the actual industrial process of sardine canning in a highly automated plant. I photographed the process in assembly-line order, from the beginning to the conclusion. As I mentioned earlier, Stinson was using frozen herring. Although fresh fish are handled slightly differently at the beginning of the process than the boxed, frozen fish, most of the steps for turning them into canned sardines remain the same. While I tried to photograph every employee and every process, there are gaps in my collection of images. Not all of the people who worked at Stinson were present during the time I was there and some expressed a desire not to be photographed. One major omission occurred because I forgot to photograph the steam plant, which not only supplied the building with heat but also provided the steam used in the canning process itself, in both the pre-cooking phase and for sterilization in the retorts. Unfortunately, all of that equipment had been removed and shipped (including the chimney!) by the time I returned to Prospect Harbor a month later, and so the opportunity to correct this oversight was lost.

Next page