ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to acknowledge the help and inspiration of those who made this book possible. First, I am indebted to all the writers and cooks whose works brought me closer to the culture and cooking of Asia. This endeavor would not have been possible without the knowledge and understanding that I gained from reading their writings.

I would also like to give special thanks to those individuals who generously gave of their time to help me with some of the chapters. Their opinions and knowledge were invaluable: Zhang Yaqi, formerly an exchange teacher from Hunan Teachers University, for the chapter on China; Prasad Vasireddi, for India and Pakistan, who generously shared with me his lively interest and study of the culture of his country India and its neighbor; Jan Vanlent, who lived and worked in Indonesia for more than thirty years; Grace Kobayashi, for her expert help and enthusiasm regarding Japan; and Clare You, who besides being a wonderful Korean cook, teaches Korean at the University of California, Berkeley, and writes about Korean language and linguistics. Thanks also to Helen Black, R.D., for her professional opinions on diet and cooking technique, and to Lynda Robinson for her help in making some difficult decisions. Last but not least, my debt to Sara Sclarenco, for her encouragement when my energies flagged. I am deeply grateful to all.

Thanks also to The Centrea meeting place for families from all over the world who are visiting the United States as students and scholarsat the University of California, Berkeley. They have enriched our lives by generously sharing their foods and customs.

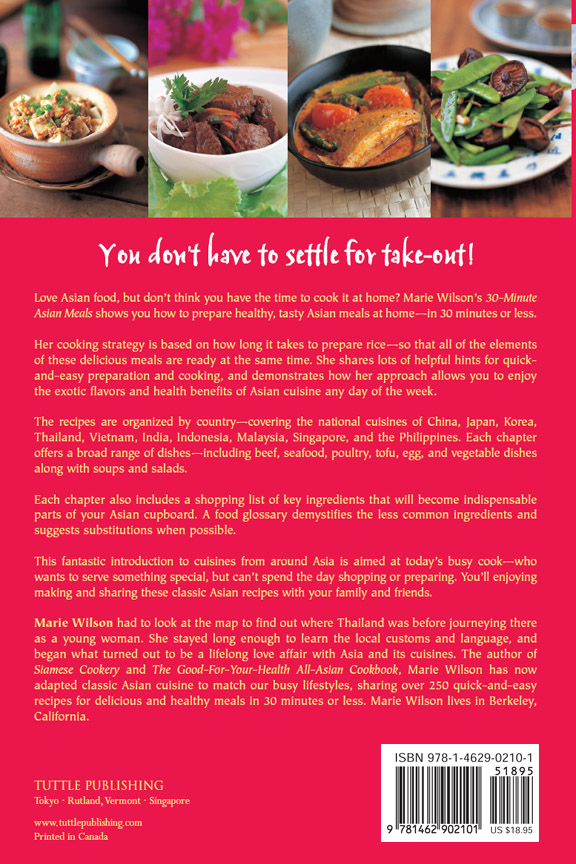

C hina's cuisine, with a recorded history that spans more than 3,000 years, is the most complex and sophisticated in the world. From earliest times, respect, even reverence, for food has permeated all levels of society, from the peasant working his tiny plot of land for his family's survival, to the scholars, princes, and emperors who placed gastronomy alongside philosophy, literature, and the fine arts. Some even wrote treatises and lyrical poems on the subject. During the Ching Dynasty (1644-1912) when the imperial court indulged in an elaborate style of luxurious living and dining, Chinese cuisine reached a peak that may never be surpassed. The closest western equivalent in technique and philosophy is French haute cuisine and the 1825 book, The Physiology of Taste, by Brillat-Savarin.

What characterizes Chinese cuisine is its inventive and adventurous use of so many uncommon ingredients. Every possible taste sensation is relished, from the humble cabbage to the improbable bird's nest. Poetry and whimsy also inform the names of some Chinese dishes. There are squirrelfish, drunken chicken, Peking dust, and monkey head (made of mushrooms).

A humorous legend aptly illustrates this whimsical approach. When a Manchu Dynasty emperor was touring Hangzhou, he stopped at a peasant food stand and asked to be served lunch. The peasant was terrified that he could not produce a dish worthy of the emperor, but he did his best. The emperor was so pleased that he asked the peasant what the dish was called. Not wanting the emperor to know what was really in the dish, he called it "red-beaked green parrot with jade cake." After the emperor had executed several chefs for their inability to reproduce this dish (the emperor's chefs cooked a parrot and served it with a piece of real jade), the peasant was summoned to the palace. He confessed that the dish was actually made of red-rooted green spinach and fried tofu.

Some suggest that the Chinese preoccupation with food is the result of chronic food shortages. With only a small proportion of its total land area suitable for farming, producing an adequate food supply for China's huge population has always been a serious problem. There was not only a scarcity of food but also a scarcity of fuel (which led to the brazier, in which any fuel could be burned), and also to stir-fryingthe quick cooking of small pieces of food in a little oil over very high heat.

But economy was not all. Taste was also important. The Chinese philosophy of taste in food has always emphasized the harmonious blending of flavors, textures and colors. The five tastessalty, sweet, sour, bitter, and spicymust all be paid the proper attention so that they are harmoniously combined, with no one accent dominating a meal. The primary purpose of these tastes is the accentuation, rather than the concealment, of natural flavors. Rich foods must be balanced by blandness, bright colors by subtle ones, smoothness with rougher textures, and hot with cold. Contrast, or dynamic balance, echoes one tenet of Taoism, the religion that held a place among the Chinese as important as Confucianism and Buddhism. Taoism (Way of Nature) sees a duality in the universe, a division in its power, with one half working against the other, not in hostility but for the sake of harmonious existence. These two halves are known as Yin and Yang.

Food shortages are no longer a problem in China, and it appears that the majority of the people are reasonably well fed. Food grains are the principal crops, which include wheat, rice, corn and millet. Rice is the leading food grain, and China is the world's leading rice producer. Although traditionally grown in the warmer lands of central and southern China, rice can now be grown in every province as a result of the development of cold-tolerant hybrids. Further, although fishing is less developed than in Japan, China maintains one of the world's largest fishing industries. Its economic development is aided by abundant coal, petroleum and natural gas reserves. But despite the rapid industrialization of recent yearsChina is now the United States' third largest trading partnerit remains a predominantly agricultural country. In general, throughout China rice or noodles is the foundation of a meal, and vegetables, the main ingredient in any dish, are cooked with only small quantities of meat or fish.

The Styles of chinese Cuisine

Chinese cuisine may be divided roughly into four general cooking styles: the northern school, encompassing the city of Beijing (Peking) and northern provinces such as Shandong, Henan, and Shanxi; the eastern school, centered on the city of Shanghai and Fujian province; the southwest, or inland, school including Sichuan, Hunan, and Yunan; and the southern school of Guangxi and Guangdong, of which Canton is the capital.

The North

In the north where the weather is colder, the conditions are more suitable for growing wheat than for rice paddies. Thus, northerners depend mainly on wheat, from which they make noodles, steamed bread and dumplings. They also grow millet and barley. Until the seventeenth century, Peking (Beijing), as the home of the Imperial Palace, was the gourmet capital of China. The best chefs were recruited by emperors and encouraged to develop new dishes. The feasts and banquets they produced are legendary. Perhaps the most celebrated northern dish known in the West is Peking Duck. Likewise, Henan is famous for a dish known the world over as sweet-and-sour fish, which is made from carp caught in the Yellow River. Monkey Head is another Henan specialty, made from a large, highly prized mushroom. Northern dishes tend to be light and mildly seasoned with garlic, chives, leeks and green onions (scallions). Other influences in this region's cooking come from Mongolia, which borders China on the north. The Mongols, who were Muslim, conquered China and set up a dynasty that ruled from 1279 to 1368. They introduced the Chinese to lamb, which is the basis for Mongolian fire pot and Mongolian barbecue.

The North

The North