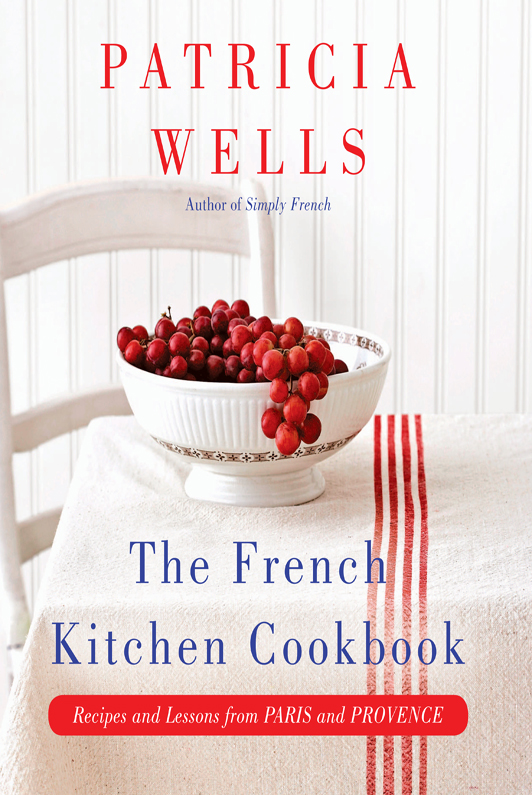

THE FRENCH KITCHEN COOKBOOK

As many times before, this book is for Walter.

For his incredible patience, his appetite for all the good

things in life, his support, companionship, fidelity,

friendship. The best husband a woman could have!

When restoring my Paris studio in 1995, I found these 1890s oak and beveled glass doors from a Paris caf, with much of the lettering still intact.

My cooking school, At Home with Patricia Wells, came about like this: As we sat around the dinner table with family and friends in Paris and Provence, guests would constantly quiz me. Tell me about sea salt, one guest would begin. Another would beg me to explain the cycle of the olive and the process of making of olive oil. Some wanted to know why a Chteauneuf-du-Pape wine rated higher than a Gigondas. And then there were market questions: How do you know when an eggplant, a tomato, a zucchini, is at its peak of ripeness?

I would then give a brief but hopefully informative response, but I soon began to think about expanding what was already a pretty full career in food. As restaurant critic for the International Herald Tribune and author of several guidebooks and many cookbooks, I already had plenty on my plate. But our haven in Provencethe eighteenth-century farmhouse known as Chanteducbegged to be shared. It also begged to hear even more sounds of laughter, friendship, and good times in the kitchen and garden and around the table.

So in 1995 we were ready to test the idea of a cooking school, one much like the memorable weeklong classes I had attended years before with Marcella Hazan and other illustrious teachers. But I did wonder: Would anyone come? Would we even enjoy doing it? We began with just two weeklong classes that September, and since then we have never looked back.

If I made a list of our hundred closest friends, a good number of them would have started out as studentsstrangers before they found their way up the hill to our ancient Provenal mas, or into the courtyard and up the stairs to my cooking studio in Paris. Soon we began to realize that we must be doing something right, for students came back again and again, as many as six or seven times. Over the years, we expanded and contracted, adding Paris classes in my cooking studio on Rue Jacob in the 6th arrondissement, conducting special weeks to study truffles, wine, fish, and shellfish, and to balance food and fitness. We even took the school off campus several times, conducting weeklong classes in Florence, Venice, Verona, and Vietnam.

This book is a compilation and reflection on what weve learned, the students and I, as we have prepared meals together. What joys people experience as they accomplish something they never imagined they would: the overwhelming feeling of satisfaction from the preparation of a perfect fruit tart; the pleasure of extracting a warm, fragrant, golden brioche from the oven; the giddiness of sharing a meal with a group of former strangers who quickly become lifelong friends.

This is a cookbook, of course, but it is just as much about my life in cooking, the way I instruct, the way I organize, the way I anticipate, the way I direct, the way I collect, the way I constantly test and retest and experiment. It is about simplicity, it is about complexity. But all in all, it is about a way of life and a lifestyle of food and entertaining.

There are days when we want a challenge in cooking as well as the exhilaration of making a truly memorable wintry beef daube, a stunning tomato tatin that captures wows from the guests at the table, gorgeous puff pastry cheese wands that could grace the window of Pariss finest pastry shop. We are willing to devote the time and effort in exchange for the anticipated reward.

Then there are days when we just want to get dinner on the table in a matter of minutes, turning to a quick sirloin carpaccio or a salmon sashimi, an instant thin-crust pizza that can be made in less than thirty minutes start to finish, a sorbet that takes seconds to make and comes to a rich and delicate life of its own as we sit down at the table.

In my classes, I like to offer students both choices, as I offer them myself daily. Many days, nothing gives me greater pleasure than to rise early, go through my routine of hiking, running, treadmill, or whatever it is that day, then spend the day in the kitchen. Testing, retesting, creating, inventing. And then there are days when I dont have a second to think about cooking: Maybe its a day of errands, appointments, and so on, and when dinnertime comes, I really havent a clue. Thats when I turn to the instant-pleasure recipes that are included here.

Over the years, I have watched as total novices in the kitchen are transformed into confident cooks, and beam as they and their fellow students put together a veritable seasonal feast. Almost all my students are eager amateurs willing to learn any truc that will lead to greater success and satisfaction in the kitchen.

I dont lecture, but I do make it clear that certain rules should be followed in the kitchen. Here are a few of the most important:

LEARNING TO COOK: Over the years, novices have asked me quite simply, But how do I learn to cook? I tell them to sit down and make a list of the ten things they most love to eat. It may be French fries or a lemon tart. A perfect puff pastry or chocolate cake. I suggest the list be varied (not all desserts, please). Then, as though you are a pianist learning to play a piece of music, you cook, cook, cook! Practice that first recipe until you feel you have mastered it, or at least have made it taste as good as you think you can at this point. Then move on to the second recipe on the list, and so on. By the time you have reached the tenth recipe, you will have a basic repertoire. Then, of course, make another list of ten and continue the process.

READ THE RECIPE: Most mistakes are made by not reading the recipe carefully or visualizing the final product. I take great care in recipe writing (and constant rewriting) to make every step as clear as possible, making it easier on everyone, giving us all a chance of success in the end.

MISE EN PLACE: meaning everything in place. In my cooking school as well as when I am cooking by myself, recipes are enclosed in a small plastic folder, and all ingredients are measured and set out neatly on a tray. This way, if I use up the last egg or drop of vanilla extract, those ingredients are instantly written out on the shopping list hanging in the kitchen. Mise en place means the cook has not only weighed, measured, washed, and chopped, but has checked the recipe for any missing ingredients, lined up equipment such as spatulas and blenders, and preheated the oven if necessary. Mise en place also makes for a neater kitchen, and I find that when the kitchen is neat, there is less chance for disaster or hysteria. (Theres another advantage to all that pre-measuring and collecting of ingredients: If you put something in the oven and turn around to find youve forgotten an important ingredient, you can most likely go back to the drawing board and repair any potential mistakes.)

Next page