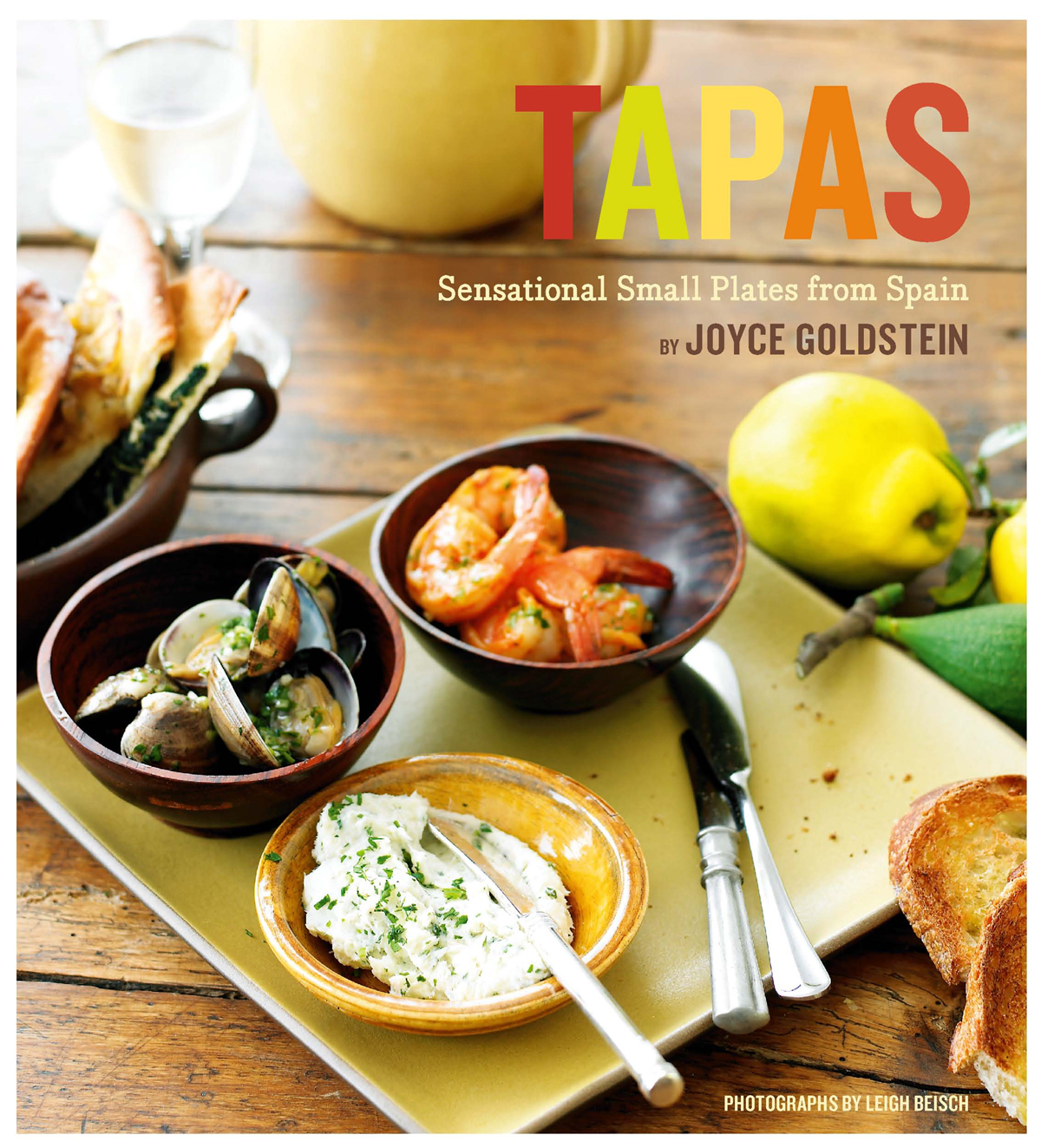

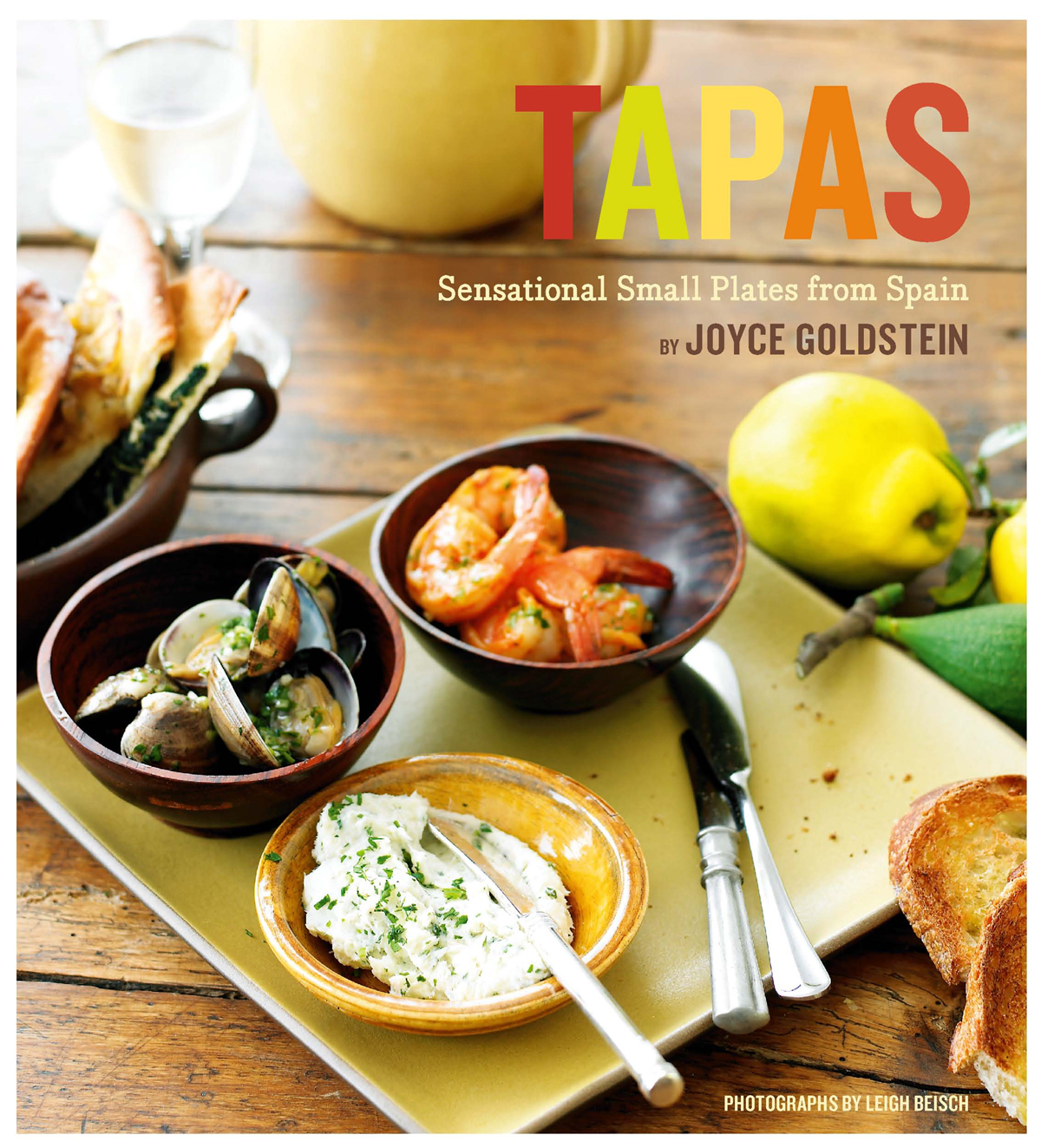

For Adam and Elena, the Tapas kids.

Muchas Gracias to:

BILL LEBLOND , longtime editor and dear friend AMY TREADWELL for her eagle eye and organization skills SHARON SILVA , the goddess of copyediting, at the top of her game, as usual

My son EVAN for his excellent wine notes and love of Spanish wine and food, and for encouraging Adam and Elena to taste endless tapas in Spain and at home

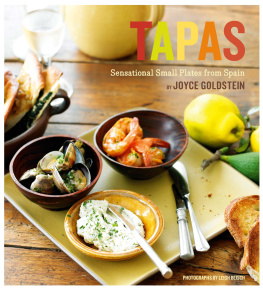

Photographer LEIGH BEISCH for yet another fabulous set of photos to make you hungry

Food stylist SARA SLAVIN for her impeccable eye and taste in props

SANDRA COOK for cooking the food so it looks yummy, and enjoying tasting the results

Designer ALICE CHAU for her very clear and elegant design and graphics

LARS KRONMARK for his passion for tapas and our long conversations about Spanish food plus time spent in the kitchen

GREG DRESCHER for inviting me to participate in the extraordinary CIA Worlds of Flavors conferences

JIM PORIS of Food Arts for assigning me the European Pepper powder piece

FOODS OF SPAIN for sending me to Madrid (Jeffrey Shaw, Mercedes Lamamie, Paz Tintore) and for enthusiastic support

KATRIN NAELAPAA of Wines of Spain for all those wonderful tastings

CLARA MARIA DE AMEZUA for her gracious hospitality CHRIS TRACY of Calphalon for those perfect tapas pans

Ever since my first visit to Spain in 1960, I have been captivated by its cuisine. At the time, the United States had few authentic Spanish restaurants and American cooks had limited access to authentic Spanish food products. I was a lonely culinary cheerleader for the Spanish table, and I struggled to cook its recipes with a combination of traditional and improvised ingredients. In 1984, I opened Square One, a San Francisco restaurant that focused on the foods of the Mediterranean, and I included many Spanish dishes on the menu. Within a year, I was offering a tapas assortment on alternating weekends. These small bites proved a seductive and successful way to introduce new dishes to diners. In my many years as a chef and cooking teacher, I have learned that some cuisines take time to capture the publics imaginationthat patience and persistence are required. Slowly but surely, Spain has simmered its way into our culinary consciousness. Nowadays, it is piping hot.

There are many reasons for this heightened awareness: the growth of culinary and cultural tourism, the greater availability of Spanish food products and wines, the press coverage of Spains avantgarde celebrity chefs, and the growing popularity of tapas. In fact, Spain is now aggressively marketing its products in the United States, and store shelves and Web sites display everything from Spanish olives, olive oil, rice, tuna, and cheeses to chorizo, serrano ham, boquerones, membrillo, Marcona almonds, and wines. In other words, contemporary American cooks can easily find whatever they need to put together a Spanish meal.

Of course, Spanish food has changed over the years, too. Following the decades-long Franco dictatorship, and the consequent stasis in the Spanish kitchen, a quiet culinary revolution took place. It was as if someone had opened the dark, heavy drapes in a living room to let in the sunlight. In the 1970s, a group of chefs in the Basque city of San Sebastin, led by Juan Mari Arzak and inspired by French nouvelle cuisine, created a new and exciting Basque cuisine that stressed lighter dishes, yet did not discard tradition. Their innovation provided the impetus for other Spanish chefs to experiment, and soon chefs around the country were exploring new ways to present their national cuisine. But news of a growing inventiveness in the Spanish kitchen did not reach far beyond the countrys borders.

That obscurity changed with the rise of Ferran Adri in the mid-1980s. This brilliant Spanish chef, with his foams, geles, and liquid nitrogen; his experimental laboratory in Barcelona; and his deconstruction of recipes into components with unexpected textures and temperatures, captured the imagination of the press, the professional culinary establishment, and the dining public. His El Bulli restaurant in Rosas, open only six months each year and famous for its elaborate multicourse menus, is always fully booked, with a long waiting list. Adri is most often linked to so-called molecular cuisine, a largely chef-centric movement that is impractical for home cooks, and he has inspired many young chefs around the world. Even more important, he has provided Spanish chefs with renewed inspiration to catapult traditional Spanish cooking into the present, with vibrant presentations and fuller, more charismatic flavors.

But after years of waiting in the wings, what finally pushed the Spanish kitchen into the Americas culinary spotlight was one of its traditions: tapas. The recent growth of American wine bars and restaurants offering a small-plate menu owes a big debt to Spanish tapas. It is not that Spain invented informal small-plate dining. Indeed, countries all around the Mediterranean are known for their rich assortments of small plates, from Italian antipasti and French hors doeuvres to Greek and North African mezes. These new American small-plate restaurants typically reflect that diversity, putting dishes from all of those traditionsand moreon the same menu. But they invariably call their offerings tapas. Even when the menu promises Spanish tapas, the plates often fuse recipes from the Iberian kitchen with those of Latin America.

In these pages, you will find only the tapas of Spain, which are abundant, varied, and delightful, with a focus on traditional plates with deep regional roots. But I have also explored how these time-honored dishes have evolved to yield interesting modern interpretations that continue to respect the past.

A National Institution

Most food scholars agree that the tapas tradition originated in the wine-growing regions of Andalusia, eventually spreading throughout the country. The Moors (Muslim Arabs), who dominated Spain from the beginning of the eighth century until the end of the fifteenth century, settled in the same area, and their meze tradition undoubtedly had an influence on the rise of the tapa.

The word itself comes from tapar, to cover, and Spanish folklore offers its own stories of origin. Among the most popular is that a slice of bread was traditionally set atop a glass of sherry or other wine to prevent any dirtor some say fliesfrom tainting the drink. Soon a slice of ham or cheese was added to the bread and the tapa was born. Another tale attributes the birth to a decree by Alfonso X instructing all inns to serve tidbits of food with the wine they poured to ensure against public drunkenness. Regardless of the true origin, the drink accompanied by the snack quickly led to el tapeo, essentially the Spanish version of the English pub crawl.

A look at the Spanish dining timetable will help you to understand how tapas dining has evolved into a national institution. Spaniards eat a series of small meals throughout the day and evening. El desayuno, or breakfast, is just coffee and a roll, quite early; and then a snack at about 11:00; la comida, or the main meal of the day, at 1:30 or 2:00, followed by a siesta; another snack, la merenda, at about 5:00, tapas at around 8:00, and a light dinner,

Next page