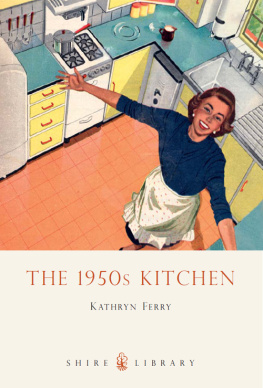

THE 1950s KITCHEN

Kathryn Ferry

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

HEART OF THE HOME

An archetypal vision of the 1950s family. Father arrives home to find the mother of his two children cooking dinner in their bright, labour-saving kitchen.

T HE MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY witnessed an historic change in kitchen design. Within the space of a single lifetime the functional back-stairs area of the house underwent a butterfly-like transformation into the colourful heart of the home. In a special fourteen-page kitchen supplement published in February 1953, Picture Post marvelled at how

[t]he modern housewifes kitchen would have astonished her grandmother. Instead of the dark, ill-ventilated cave which she knew, the kitchen of today is light, airy, and highly equipped. Its separate components are carefully planned to make a complete, working unit. It is gracious, comfortable and efficient. Or it should be!

Gone was the Victorian model of a room inhabited by paid staff and set apart from family life. Social changes contingent upon two world wars and rapid technological advance had fundamentally changed expectations of who used the kitchen and what activities took place there.

By the end of the Second World War servants had virtually disappeared. The great pool of cheap female labour that had sustained the British tradition of domestic service, allowing even lower-middle-class households to employ a maid in 1900, had dried up in the face of more attractive employment opportunities. Girls who emerged from munitions factories after the First World War did so with a growing sense of their own capabilities. That they favoured the relative freedom of factory, clerical or shop work meant the Servant Problem became a much-debated issue of the 1920s and 1930s. Upper- and middle-class wives who had not foreseen themselves entering the kitchen other than to give instructions now learnt how inefficient they had allowed their domestic arrangements to become and the notion of labour-saving aids began to gain popular currency. In the wake of the Second World War the impetus to improve kitchens was greater still as full employment and rising living standards contributed to a major social levelling. A steadily increasing proportion of married women opted to stay in paid employment alongside their unmarried sisters and although an outside job did not negate the rigid assumption of kitchen as feminine space it did supply money to pay for gadgets and appliances that could ease the burden of work.

The women who returned to family life post-war or started out as housewives for the first time, whether middle or working class, now shared the common status of home labourer. Society encouraged them to take satisfaction in perfecting their domestic skills despite the potentially endless routine that came from combining the roles of cook, dishwasher, laundress, cleaner, nurse and hostess. As a result, when prosperity returned to Britain in the 1950s, the kitchen assumed greater prominence in household purchasing decisions. A 1950 editorial in Womans Own proclaimed,

This is the room more than any other you love to keep shining and bright A womans place? Yes, it is! For it is the heart and centre of the meaning of home. The place where, day after day, you make with your hands the gifts of love.

The 1952 kitchen-dining room of a house at Chipping Field, the first estate built at Harlow New Town, Essex. The simple white wooden cupboards of post-war local authority housing were practical but lacked the streamlined glamour of later fitted units.

It was an attractive vision after the disruption of wartime separations and as the housewife took up residence in the kitchen her husband, children and guests joined her there.

The post-war era generally saw a move towards greater informality in household arrangements and the severe housing shortage offered a unique opportunity for architectural design to reflect this social change. Enemy air raids had punctured the streets of British towns and cities 475,000 homes were left destroyed or uninhabitable; a greater number again suffered significant damage while the wartime surge in marriages ensured that this drastic reduction in supply was combined with an unprecedented increase in demand. As part of the governments recovery agenda local authorities embarked on ambitious building programmes, beginning with estates of temporary prefab dwellings and including the creation, from 1946, of fourteen New Towns. Smaller houses became the norm, both because there was intense pressure on land, labour and building materials and because they were easier for the modern nuclear family to heat and manage. The function of rooms also came under scrutiny as planners sought to maximise the limited space available.

Working-class women had long experience of combined kitchen-living rooms but, higher up the social scale, the implication of not being able to afford separate spaces generated snobbery against eating food in the same place as it was prepared. This stigma disappeared after the war. Multi-purpose rooms were now deemed to be fashionably modern and open planning became a statement of contemporary architecture, most influentially promoted in the Californian Case Study Houses designed by the likes of Charles and Ray Eames and Pierre Koenig. Although their radical vision of free-flowing space in sophisticated glass boxes was too advanced for most British families, steps were taken to assimilate the kitchen better into the rest of the post-war house. In the Homes and Gardens Pavilion at the 1951 Festival of Britain a series of architect-designed kitchen-dining rooms suggested ways to achieve this using movable screens and folding walls. A more widely endorsed solution was the dining recess or breakfast nook divided from the cooking area by an open sideboard or shelf unit. Where the kitchen and dining room remained as distinct entities a serving hatch was a highly coveted innovation. Mrs Martha Long watched the construction of her future home in a Hackney tower block and later recalled that, alongside the balcony, the serving hatch was the flats chief attraction. Introduced during the 1920s to assist butlers in the easy service of meals and the rapid return of dirty dishes to the kitchen, by the 1950s serving hatches were in everyday family use, found in both private and council housing.

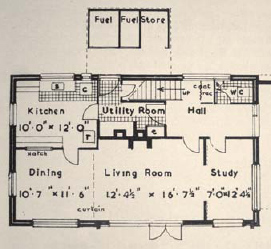

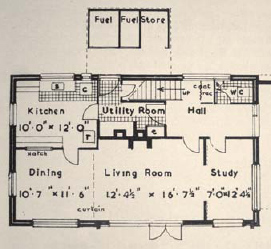

The ground floor of an architect-designed house in Kent (Daily Mail Book of House Plans, 1955). A serving hatch connects the kitchen with the dining-living room and a utility room replaces the old-fashioned scullery.