BUNGALOWS

Kathryn Ferry

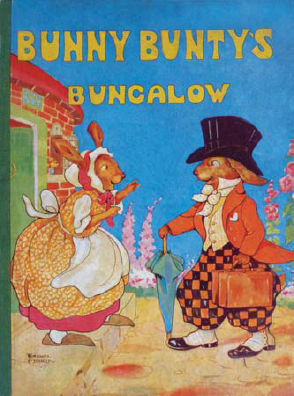

Bunny Buntys bungalow stood in the heart of Woodland. There it was for everyone to gaze at and to envy. The front cover of a 1920s childrens book by Jean Morton.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

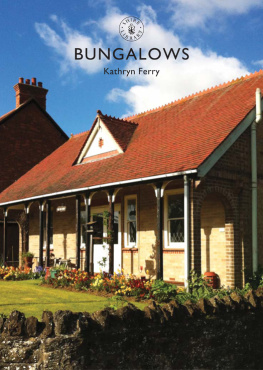

The Bungalow at Bratton in Wiltshire stands pristine in its Edwardian newness. Having rooms in the roof was not considered to be a contradiction until the bungalow settled into its modern definition after the Second World War.

CONTENTS

The Governor Generals budgerow on the Ganges, Brahmaputra Delta by Hubert Cornish (17571823). With thatched roof and verandah, this is the native hut of Bengal adapted for colonial use.

AN ELITE RETREAT

T HE FIRST BOOK specifically dedicated to bungalow design was published in 1891 by the architect Robert Alexander Briggs. Entitled Bungalows and Country Residences, it featured the following definition:

A bungalow in England has come to mean neither the sun-proof squat house of India nor the rough log hut of colder regions. It is not necessarily a one-storied building, nor is it a country cottage. A bungalow essentially is a little nook or retreat. A cottage is a little house in the country, but a bungalow is a little country house a homely, cosy little place, with verandahs and balconies, and the plan so arranged as to ensure complete comfort with a feeling of rusticity and ease.

As conceived by the Victorians, a bungalow was a building concerned with relaxation and recreation. This ensured that the earliest residents were necessarily wealthy, but rapid social change opened up the health benefits and bohemian lifestyle associated with bungalows to a wider population. The late-nineteenth-century invention of the weekend provided more free time; improved transport infrastructure made escape possible; and mass-production of materials, and even of entire structures, enabled bungalows to be built on a budget. By 1910 the word could be applied to dwellings quite different in appearance, but nonetheless united by their usage. During the inter-war building boom the weekend or holiday bungalow began to be superseded by the self-consciously labour-saving suburban bungalow. This book uncovers the bungalows early popularity both as a structure and as an idea.

The story begins on the Indian sub-continent with the Hindi and Mahratti term bangla, meaning of or belonging to Bengal. This was the basis for the words bangalla, bungelo and banggolo, in use by the seventeenth century to describe indigenous bamboo huts with mud walls, thatched roofs and verandahs, built upon raised platforms. When European traders began to settle in India, it was in this type of vernacular building that they lived. Adaption followed adoption and, as commercial interests gave way to increasing colonial control between 1770 and 1830, the Anglo-Indian bungalow emerged as a distinctive dwelling for European officials. Its prototype was clearly revealed in the similarity of design, not to mention its name, but the new purpose-built bungalow also came to be defined by a detached status within its own grounds or compound. After 1815 this type of dwelling was also erected in the newly created colonial hill stations used as temporary refuges from the stifling summer heat. This less formal setting helped lend the bungalow an aura of freedom and relaxation that influenced its future transfer to Britain.

Until the mid-eighteenth century familiarity with the term bunglo was restricted to the European community in India, but knowledge gradually filtered back to Britain. The artists Thomas and William Daniell painted influential views of Indian landscapes and antiquities during the 1780s, and William Hodges published two volumes of drawings upon his return from a six-year residence. In Travels in India, 17803 (1793), Hodges described the large bungelow of a senior East India Company officer at Lucknow, where he stayed in 1781:

Bungalows are ... generally raised on a base of brick, one, two or three feet from the ground, and consist of only one storey; the plan of them usually is a large room in the centre for an eating and sleeping room, and rooms at each corner for sleeping; the whole is covered with one general thatch, which comes low to each side, the spaces between the angle rooms are viranders or open porticos to sit in during the evenings ... Sometimes the center viranders at each end are converted into rooms.

The virander began to appear in British architecture following its inclusion in John Plaws pattern book Sketches for Country Houses, Villas and Rural Dwellings, published in 1800. Many other Indian words and ideas found their way into the everyday discourse of Victorian Britons, especially after the so-called Indian Mutiny of 1857 and the subsequent extension of imperial power. By then the bungalow was not only understood as a concept; it was also emerging as a distinctive new type of building back in Britain.

Early use of the word bungalow can be traced in the pages of The Times newspaper. A digital search returns just five mentions during the 1860s, fifteen in the 1870s, and then a massive leap to ninety-eight in the 1880s. The first time it appeared among the property advertisements was in 1862, when The Priory, near Douglas on the Isle of Man, was listed for sale as a beautiful Residence, built like an Indian bungalow. The rarity of the housing type ensured that references to Indian prototypes or the bungalow style persisted for the next decade, although The Priory itself was constructed as early as 18501. Designed by a local architect, John Robinson, it was built for Elizabeth Stevens, widow of Major Francis John Stevens, perhaps inspired by experience of military service in the East.

The location of this Indian bungalow is unknown but it was clearly judged to be a representative example of its type as its image appeared on mass-produced Edwardian postcards in sepia and colour versions.

Despite The Priorys spacious accommodation a 26- by 18-foot drawing room, a similarly proportioned dining room with conservatory, a library and ten bedrooms (including those for servants) the building did have the hallmarks of a Victorian bungalow. It was a predominantly single-storey detached property in landscaped grounds, with beautiful views from its rustic veranda. Other such residences were rare enough in their own neighbourhoods for the word on its own to be sufficient identification, for example The Bungalow at Torquay, listed in a local directory of 1859. In 18767 The Times carried references to further examples at Burghfield near Reading, Instow in Devon, Maidenhead on the River Thames and Worcester Park in Surrey.