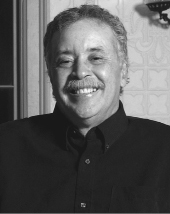

B ryan Prince is a much-respected historical researcher with a particular interest in the Underground Railroad, slavery, and abolition. The author of two bestselling books, I Came as a Stranger and A Shadow on the Household , he is much in demand as a presenter throughout Canada and the United States. Prince and his wife, Shannon, were awarded the 2011 prize for the Advancement of Knowledge by the Underground Railroad Free Press . They live in North Buxton, Ontario.

Acknowledgement

Acknowlegements, Notes on Sources, and the Case of The Two Isaac Browns

M y interest in Isaac Brown was first kindled in January 1977. As did millions of others, I sat in front of a television set for eight consecutive nights, mesmerized by the dramatization of Alex Haleys book Roots. Although fascinated with history from an early age, and despite growing up in Buxton, which was once a haven for fugitive slaves and was then (as now) a place that had a museum that celebrated the stories of those remarkable people, I had never taken the time to find out about my own ancestors. Watching that miniseries irrevocably changed that.

The first steps were to grill parents, grandfather, great aunts, and more distant cousins. Sadly, they knew but little of our family history in the days before emancipation, a fact that I came to learn was not uncommon among people of African descent. Visits to both nearby and more distant museums, libraries, and historians gradually revealed tiny bits of the fragmented recorded individual stories. The generous-hearted members of the Kent Branch Genealogical Society, particularly Helen Blackburn, Wendy Barry, and Joan Griffin, although strangers to me at the time, were helpful beyond belief in supplying information and guiding me to the records that might reveal some small detail that would add some flesh to the bones of long-deceased relatives.

I first learned of my great-great-great-grandfather, Isaac Brown, thanks to the late Arlie Robbinss pioneering research on early enslaved families who fled to Canada in the mid-nineteenth century. Arlies voluminous notes and family trees, deposited in the museum that she helped found in 1967 (then known as The Raleigh Township Centennial Museum now rechristened The Buxton National Historic Site & Museum) included mention of Isaac Brown and his family, all of whom were among the earliest residents of The Elgin Settlement and Buxton Mission, Canadas largest planned settlement for fugitive slaves.

Months of research added pieces to the puzzle that was Isaac Brown. The search for early tangible details on all of the family members was difficult since the 1851 census for Raleigh Township is lost. Thankfully, the Chatham Kent Registry Office has microfilmed copies of the land transactions, which revealed that on September 3, 1851, Isaac Brown, yeoman, bought one acre on the military road that was at the very heart Buxton, comprised of the northern half of Lot 9, Concession 12 in Raleigh Township. He paid Joshua and Elizabeth Shepley two hundred pounds of lawful money of Canada. The deed contains a heart-wrenching clause. Although the Shepleys were willing to sell their farm, they could not bear to lose title to a tiny sacred portion, and included the phrase: excepting a small part of the said half lot containing the graves of three children of said grantor and extending one foot each way beyond the said graves.

The annual tax records, now housed at the Buxton Museum, thanks to the generous donation of the late Clarence and Cookie Pratt, reveal ever-evolving personal and property information. In 1852, Isaac Brown is listed as fifty-six years old. In addition to his land, he owned two horses worth $20.00 and two cows worth $4.00. By the next year he has acquired an additional fifty acres, across the road from his original purchase.

According to a printed copy of the proceedings, which are held in Cornell Universitys amazing Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection (much of which is available online), Isaac represented Buxton at a General Convention for the Improvement of the Colored Inhabitants of Canada held at the First Baptist Church in Amherstburg on June 16 and 17, 1853. The list of delegates was a whos who of black community leaders from Amherstburg, Anderdon, Buxton, Colchester, Dresden, and Chatham, all in the southern part of Canada West; as well as from Detroit, Michigan, Madison, Indiana, and from Cleveland, Oberlin, and Urbana, Ohio, in the United States.

Isaacs status is confirmed by his appointment by his peers to be a member of the Business Committee. After thoughtful deliberation, this committee made recommendations on the subjects of emigration, agriculture, temperance, education, statistics, finances, and a constitution for a Provincial League. The members vilified the United States government for its inhumanity, but praised Queen Victoria and Canada for offering an asylum, and vowed to defend the country whenever called upon. They thanked Harriet Beecher Stowe for her monumental work Uncle Toms Cabin , which exposed slavery in a light not previously shown . Showing that they had not forgotten their own past, they agreed to offer a letter of support for a fundraising effort to purchase and free the sister of a Canadian minister who was to be sold from Virginia to the Deep South. They also denounced the system of begging that brought shame to the former slaves who wanted to remove any question as to their ambition and independence. Isaac Brown was one of five men appointed to an executive committee to ensure that the recommendations of the conference were carried out and that arrangements be made for a like meeting the following year. These men were also charged with the daunting task to supervise the general interest of the colored people of Canada.

By 1854 the Raleigh tax assessor noted that Isaac had two dogs one of those small details that helps paint a picture of a familial scene. The total property was valued at $325, and, based on that, Isaac was assessed to perform seven days statute labour, which was the obligation of each male citizen to perform public work, such as building roads or drainage ditches. According to Raleigh Township published records held by the Buxton Museum, as well as some in my personal collection, on January 29, 1855, the Township Council recognized Isaac for the respect he had earned when they appointed him Fence Viewer, to settle property line disputes, oversee proper dimensions of fences, and other such responsibilities. This was an extremely important position at the time as farms were being surveyed out of virgin forest and lot lines were inexactly delineated by an axes notch on a tree.

That same year, Isaac and his wife Mary Jane, along with the founder of the Buxton Settlement and their neighbour Reverend William King and his wife Jemima, each mortgaged one of their farms by jointly borrowing four hundred pounds from the Commercial Building and Investment Society of Toronto. On that document, Isaac signed his name rather than making his mark with an X as he had done on his original deed. Also interesting from a human standpoint, the farm that Isaac and Mary Jane mortgaged was now one hundred acres minus an area containing six graves. Perhaps Isaac himself was soon to enlarge that area. The year 1855 is the final time that he, at age fifty-eight, was listed in the tax records. Beginning in 1856, his home farm is listed under his widow Mary Jane Brown and his second farm under his son-in-law Edward Prince, who had married the Browns daughter, Eliza.