Jim Tolpin's Guide to Becoming a

Professional

Cabinetmaker

Jim Tolpin's Guide to Becoming a Professional Cabinetmaker. Copyright 2005 by Jim Tolpin. Printed and bound in China. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published by Popular Woodworking Books, an imprint of F+W Publications, Inc., 4700 East Galbraith Road, Cincinnati, Ohio 45236. First edition.

Distributed in Canada by Fraser Direct

100 Armstrong Avenue

Georgetown, Ontario L7G 5S4

Canada

Distributed in the U.K. and Europe by David & Charles

Brunel House

Newton Abbot

Devon TQ12 4PU

England

Tel: (+44) 1626 323200

Fax: (+44) 1626 323319

E-mail: mail@davidandcharles.co.uk

Distributed in Australia by Capricorn Link

P.O. Box 704

Windsor, NSW 2756

Australia

Visit our Web site at www.popularwoodworking.com for information on more resources for woodworkers.

Other fine Popular Woodworking Books are available from your local book-store or direct from the publisher.

09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tolpin, Jim, 1947

Jim Tolpin's guide to becoming a professional cabinetmaker/ Jim Tolpin.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 1-55870-753-0 (pbk: alk. paper)

eISBN 13: 978-1-4403-1614-2

1. Workshops. 2. Cabinetwork. 3. Cabinetmakers. I. Title: Guide to becoming a professional cabinetmaker. II. Title.

TT152.T65 2005

684.1'.04 dc22 2005003054

ACQUISITIONS EDITOR: Jim Stack

EDITOR: Amy Hattersley

DESIGNER: Brian Roeth

ILLUSTRATOR: Len Churchill

LAYOUT ARTIST: Kathy Gardner

COVER PHOTOGRAPHER: Tim Grondin

PRODUCTION COORDINATOR: Jennifer Wagner

Read This Important Safety Notice

To prevent accidents, keep safety in mind while you work. Use the safety guards installed on power equipment; they are for your protection. When working on power equipment, keep fingers away from saw blades, wear safety goggles to prevent injuries from flying wood chips and sawdust and wear headphones to protect your hearing. Consider installing a dust vacuum to reduce the amount of airborne sawdust in your woodshop. Don't wear loose clothing, such as neckties or loose-sleeved shirts, or jewelry, such as rings, necklaces or bracelets, when working on power equipment. Tie back long hair to prevent it from getting caught in your equipment. People who are sensitive to certain chemicals should check the chemical content of any product before using it. The authors and editors who compiled this book have tried to make the contents as accurate and correct as possible. Plans, illustrations, photographs and text have been carefully checked. All instructions, plans and projects should be carefully read, studied and understood before beginning construction. In some photos, power tool guards have been removed to more clearly show the operation being demonstrated. Always use all safety guards and attachments that come with your power tools. Due to the variability of local conditions, construction materials, skill levels, etc., neither the author nor Popular Woodworking Books assumes any responsibility for any accidents, injuries, damages or other losses incurred resulting from the material presented in this book. Prices listed for supplies and equipment were current at the time of publication and are subject to change. Glass shelving should have all edges polished and must be tempered. Untempered glass shelves may shatter and can cause serious bodily injury. Tempered shelves are very strong; if they break they will just crumble, minimizing personal injury.

I dedicate this book to Alysha Waters, who rode life's other merry-go-round as we both reached for the golden ring.

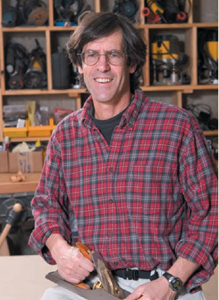

About the Author

Jim Tolpin has operated a finish carpentry and custom cabinetmaking business since 1969. He has written numerous books on the woodworking trade including Measure Twice, Cut Once; Building Traditional Kitchen Cabinets; Jim Tolpin's Table Saw Magic; and Jim Tolpin's Woodworking Wit & Wisdom.

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the following good people, who, sometimes unwittingly, taught me something I needed to know: Sam Rosoff, Irving Pregozen, Jay Leech, Ludwig Furtner, Warren Wilson, John Muxie, Steven Souder, Johnny Coyne, Frank Whittemore, David Sawyer, Doug Fowle, Dan Valenza, Bud McIntosh, Diane Gusset, Ken Kellman, Daniel Neville, John Ewald, Chris Marrs, Charles Landau, John Maurer and Walter and Susan Melton. If not for them, I'd still be holding the dumb end of the tape. Special thanks to cabinet-maker John Marckworth for loaning us some tools, his shop and even his person for some of the photography and to Seb Eggert of Maisefield Mantels for loaning us his entire shop for a couple of hours for a photo shoot!

I am especially indebted to Francis Nat Natali, who showed me that learning to write is not unlike learning to ride a bicycle Just keep at it and you'll find that the balance comes of its own and to Laura Tringali, who kicked off the training wheels. At F+W Publications, thanks to Jim Stack, David Lewis and all the others who helped bring this book to market. Finally, I wish to thank photographers Pat Cudahy and Craig Wester for their skills and perseverance.

introduction

IT'S BEEN MORE THAN 30 YEARS SINCE I FIRST started working at woodworking. In the beginning, I worked alone in a one-car garage outfitted with a minimal number of tools. Today I am the sole proprietor of a one-man cabinet shop, and I work out of a two-car garage outfitted with a minimal number of tools.

IT'S BEEN MORE THAN 30 YEARS SINCE I FIRST started working at woodworking. In the beginning, I worked alone in a one-car garage outfitted with a minimal number of tools. Today I am the sole proprietor of a one-man cabinet shop, and I work out of a two-car garage outfitted with a minimal number of tools.

That boy's gone far, I can hear you saying. Now he has room for a second car. There is, however, an even greater difference: This boy can now afford a second car. In my first 10 years of working wood for a living, I could barely provide for myself or the family of four I now support (another difference 30 years can make), let alone a second car. It was not the woodworking itself but the way in which I was working the wood that forestalled my financial success.

During those first 10 years, I often built highly refined pieces of casework that required much hand joinery and tedious fine detailing. I called the results of these efforts kitchen cabinets. With each delivery, I bathed in my clientele's enthusiastic approval of my work. Little did I realize how much of the celebration was due to their joy at obtaining such a piece at such a price at least not until the day I looked up from my work and realized that this was not cabinetmaking. I was going broke like nearly every custom furniture maker I had ever met. It had come time to unplug myself from the shop for a while and try to figure out what I was doing wrong.

Before long, I had three likely answers. First, I did not have the faintest idea about how to build cabinets in fact, I didn't really know what a kitchen cabinet was. Second, my methods and tooling, such as they were, were primitive and counterproductive. Third, I was an abysmally poor businessman. To continue practicing woodworking as a livelihood, I had to understand the market's perspective of a quality piece of cabinetry and learn how to build it as efficiently as possible. I also had to learn how to successfully present myself and my products to the public.

IT'S BEEN MORE THAN 30 YEARS SINCE I FIRST started working at woodworking. In the beginning, I worked alone in a one-car garage outfitted with a minimal number of tools. Today I am the sole proprietor of a one-man cabinet shop, and I work out of a two-car garage outfitted with a minimal number of tools.

IT'S BEEN MORE THAN 30 YEARS SINCE I FIRST started working at woodworking. In the beginning, I worked alone in a one-car garage outfitted with a minimal number of tools. Today I am the sole proprietor of a one-man cabinet shop, and I work out of a two-car garage outfitted with a minimal number of tools.