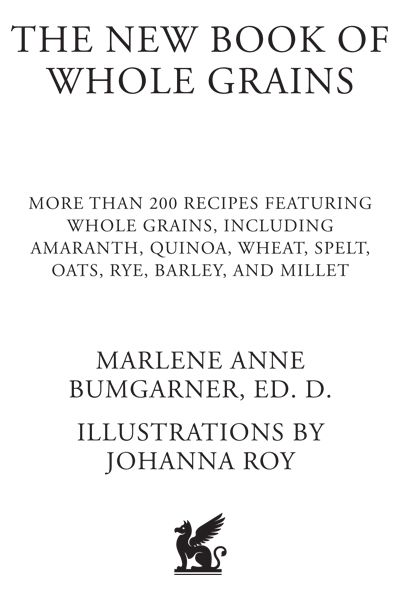

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

For Doa, John, Jamie, and Deborah

Many thanks to Boyd Foster, Al Guisto,

and all the recipe testers

When I began writing the first edition of The Book of Whole Grains I was raising my family in a rural setting; tending goats, rabbits, chickens, and ducks; harvesting vegetables from an extensive kitchen garden; and baking bread daily. We had no electricity or running water. I cooked on a woodburning stove, and typed the manuscript on a manual typewriter. When we could forget the Vietnam War, the early seventies were a romantic time for those of us who chose to move back to the land. Many young parents learned, as I did, the challenges and rewards of cooking whole and natural foods for their families.

Following the publication of the book in 1976, however, our familys life began to change. First, I was asked to write a column for the local newspaper. Then, responding to demands for a local source of whole grains, I opened a natural foods store. A second book followed, in which I tried to answer the questions asked by readers of the column and my customers. Soon, I was teaching cooking classes at the local community college.

One thing leads to another, if you allow it, and two decades later I am a tenured college instructor, teaching not only cooking, but also child development and psychology. A single parent, I no longer live on a farm, but in a centrally located townhouse. College tuitions are a very real part of my life, as are high school dances and junior high soccer games. Time to spend cooking is far more scarce than it was twenty years ago. My manuscripts are now typed on a computer, and my grown-up children send e-mail when they want to communicate.

These changes are not necessarily bad, but they have required some adjustments in the way in which I nourish my family and myself. I still enjoy baking bread, but I do it less often, and sometimes use a bread machine. Soups and stews take precious time, so they are usually accomplished on early Sunday mornings, when it is quiet and I can linger over the newspaper between stirs and sniffs. I use the freezer more, and our microwave oven has become my friend. Times change, but our bodys need for healthful food does not. The time each of us spends preparing food for others is a gift, and I share that gift with my children by encouraging them to participate.

In The New Book of Whole Grains I have tried to be conscious of the changes in the lives of modern families, and of the scarcity of time and energy people have to prepare food, or to do anything for that matter. But I have also tried to keep in the front of my mind the undeniable reality that our loved ones, and their health, are still our responsibility.

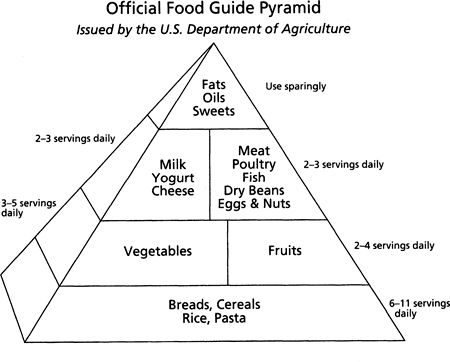

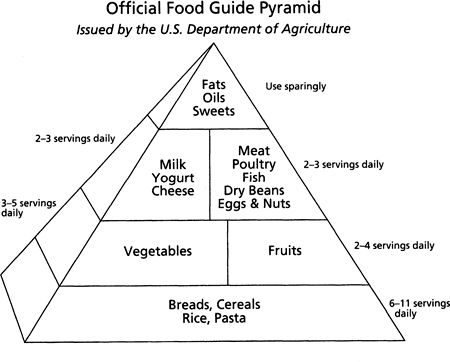

In the last twenty years we have learned much about the relationship between what we eat and how we feel, and the updated and new recipes in this book reflect that knowledge. Less fat, less salt, less meat, but no fewer whole grains; in fact, the USDA Food Guide Pyramid introduced in 1992 simply repackages the wisdom of ancient civilizations. Long before the Four Food Groupsnow discredited as encouraging a meat- and dairy-based diet leading to heart disease and cancermillions of people thrived on diets in which grains, nuts, seeds, legumes, and vegetables provided their major sources of protein as well as carbohydrates. And, contrary to the nutritional dogma of the 1970s, it now appears that as long as adequate calories are eaten from a wide variety of nutritious foods, we can ignore amino acid charts and still obtain adequate protein from plant foods.

So, as I did with my readers in 1976, I invite you to explore the world of whole foods to find the particular recipes and ways of serving them that you and your family enjoy the most, and to incorporate them into your lives permanently. Not only will you be improving your familys health and helping to reduce world food shortages, you may also find, as I have, that working in the kitchen is very satisfying, especially when it results in pleasant fragrances, flavors, and mealtimes.

Marlene Anne Bumgarner

This book is about cereals. Not cereals the way television commercials present themprecooked, prepackaged products which in no way resemble their natural formsbut cereals as the peoples of ancient times knew them: tall grasses rippling across the fields, golden ears of corn adorning graceful green stalks, heads of millet or sorghum drying on rooftops, paddies of rice planted carefully by hand.

A history of cereal grains is the story of our transition from a nomadic life to one of settlement and agriculture. Wild grasses, nuts, and seeds were once gathered by primitive groups of people in all parts of the world, then pounded into flour or roasted and eaten whole. Perhaps, returning to the same fields year after year, someone noticed that grasses badly thinned out would not reseed themselves. Or perhaps some seeds, accidentally scattered, had caused grain to grow where formerly it had not. However it began, eventually men and women who had always wandered in search of food started to plant it instead, and to remain in one place at least long enough to harvest their crop. It is no exaggeration to say that the beginning of agriculture marked the beginning of civilization, for once freed from constant foraging, our ancestors could devote their strength to building cities and the systems necessary for their survival.

Agriculture began at different times in different parts of the world, and which cereal grains were domesticated depended upon soil and climate. Food patterns that developed centuries ago have remained to this day: in Mexico, beans, corn, and rice are the staples, while in Europe, rye bread and cheese predominate. In Africa, grain sorghum and peanuts make up many meals, but Chinese and Indian people usually mix soybeans and rice.

These patterns of eating developed independently in all parts of the world, but displayed a common characteristic: the custom of combining cooked grains with beans or peas, nuts, and dairy products to form complete meals. Researchers are only now learning why these combinations worked so well, and why they endured.

Basically, the reason for such combinations is that each of the major groups of non-meat foods is missing some of the essential amino acids, ingredients necessary for our bodies to be able to make use of the protein contained in any food. If these essential amino acids are not all present simultaneously, the protein in food cannot be converted into usable form by the body, and is wasted. Grains and legumes, for example, are each deficient in some of these amino acids, but in different ones. When grains and legumes are combined in the same meal, the amount of protein which can be used by the body is considerably higher than it would have been if the grains and legumes were eaten separately. The different food groups which can be combined, and the best combinations and proportions, are discussed in Frances Moore Lapps Diet for a Small Planet. Her book is a valuable text for anyone interested in cooking whole grains.

But who wants to cook whole grains? While I was preparing this book some of my closest friends advised me, But no one really cares about using whole grains! Most people are so used to convenience foods that they simply wont bother to try your ideas. I dont believe that. While teaching in a small elementary school near my home, I taught a childrens cooking class on whole grains. Before we had completed our study, requests began coming in from mothers and fathers for recipes that we had used in our class. Conversations with these parents over the months have encouraged me in this venture. More and more, they and people like them want to learn about nutritious and economical ways to change their families diets.

Next page