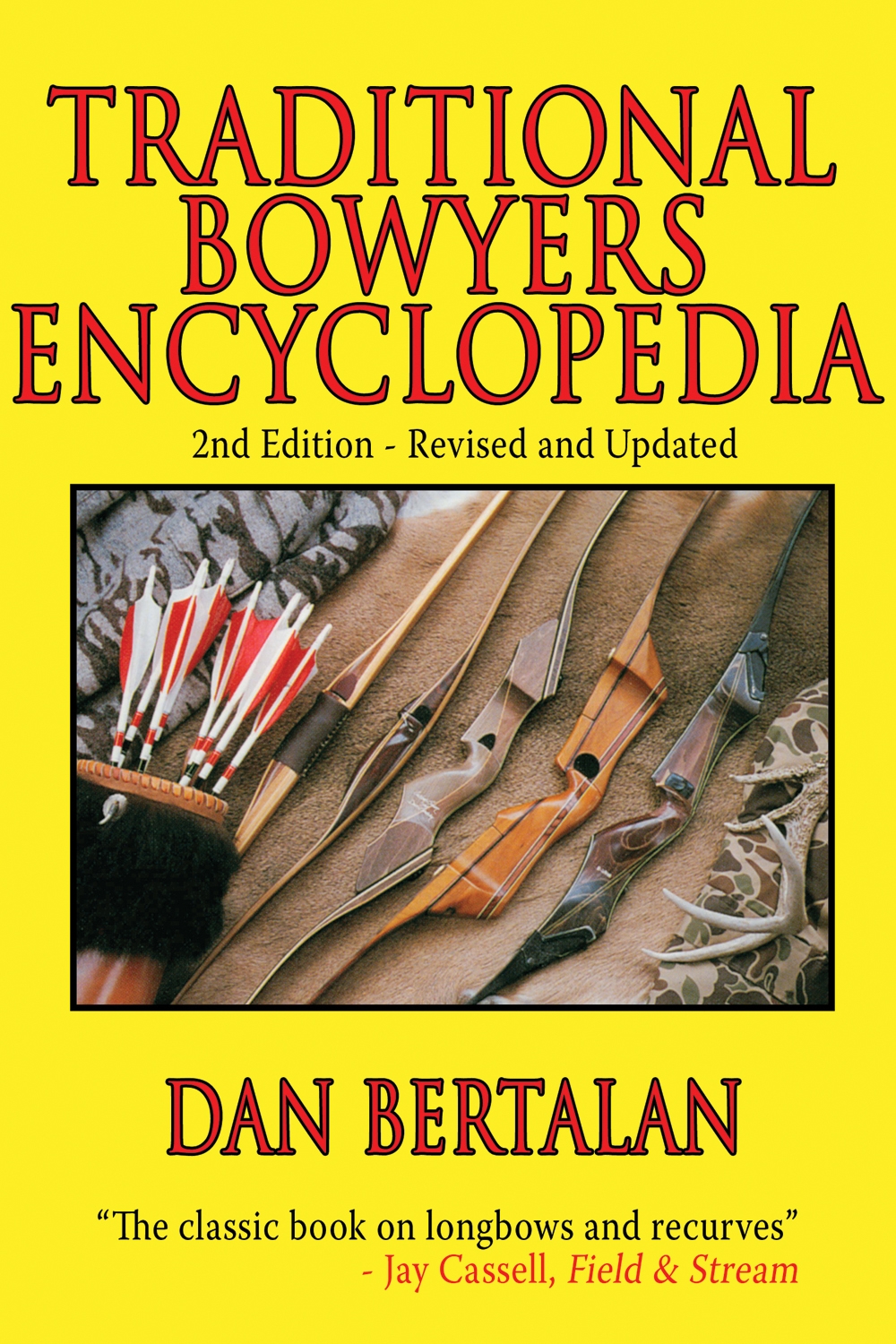

The author gratefully acknowledges the openness and help of the bowyers profiled in the following pages. The author is also grateful to Linda Peckham, Mary Brown, and Mark Woodbury for their encouragement and editorial assistance.

Epilogue

During the peaceful days when the clover blossomed, the two boys lingered near the fireside of Chu-no-wa-yahi, learning the sacred craft of fashioning man-nee. With each passing moon the old bowmaker watched the boys grow too quickly into young men, their visits becoming less frequent as they neared manhood.

Before the annual acorn harvest, the day came when the boys were ceremoniously presented with their tribal bows. The sleek bows were immaculate the ultimate reflection of the old warriors bowmaking skills and his deep love for the boys, now men. He knew their days would now be spent on the trail as hunters and warriors. He also knew his fireside would be hushed with gnawing worry for their safety. Although none would speak of it, a recent hunting party had not returned after venturing into the lowlands near the dreaded white men. Most knew they had probably been slaughtered by Saltu and his fire-spitting sticks that thundered of death.

In the chill of a leafless night, Chu-no-wa-yahi wrestled with the horror of a terrible dream. Tightly clutching his bow, he shuddered, embarking on his final journey to the land of shadows where he would hunt forever with the thousands of warriors silenced before him.

Chu-no-wa-yahi escaped the suffering his people endured. In the years that followed his passing, the raw wind howled a deathly moan at the base of the great cliff. It mingled with the mournful cries for the ever growing number of Yana killed by the invading whites.

The white men purposefully massacred the Yana of Northern California, reducing the once-proud race from several thousand to less than a dozen. Battered, hunted, and clinging to life, the remnants clamored into the desolate canyons of Deer and Mill Creeks. There, under the cover of the shadowed cliffs and dense brush, the survivors slipped into their secretive existence, disappearing from the white mans conquered world.

People mostly forgot about the staunch survivors until 1908 when a survey party surprised three of the primitives near Deer Creek. After shooting warning arrows at the party, two Indians abandoned an old crippled woman and disappeared into the brush. The survey party approached the trembling old woman, her withered legs wrapped in willow bark. Nearby they discovered two brush huts hidden in dense foliage. In typical white man fashion, they ransacked the huts, confiscating bows, arrows, and primitive utensils, and left. Returning the next day they hoped to find the Indians, but the huts were abandoned. The primitives had disappeared forever. Except for one.

For nearly three years the tales about the wild Indians of Deer Creek lingered until one morning a half-starved, ragged Indian was discovered in the small town of Oroville, over thirty miles from Deer Creek. Brought to bay in a corral by a barking dog, the wild Indian was captured and locked in the local jail for safekeeping.

Hearing of the Indians capture, Professor T.T. Waterman, from the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, visited the jail and established broken communication with the primitive. The Indian was Ishi, lone survivor of the Yana Indians.

Waterman befriended the fearful Indian and took Ishi to San Francisco and to the Museum of Anthropology where he became a subject of study. During his years at the museum, Ishi had little immunity to the white mans infectious world and was often sick. He was treated by Dr. Saxton Pope, instructor of surgery at the University Medical school.

Pope became friends with Ishi and admired him for his kindness, honesty, and high moral standards. In turn, Ishi admired Pope for his ability to learn the Yana tongue and for his deep interest in Ishis most prized possessions his bow and arrows.

Ignoring the barriers of race and culture, Ishi and Pope grew to love each other as brothers and became bonded by their common affection for the bow. Ishi taught Pope how to make, shoot, and hunt with Indian style bows and arrows. The two friends took many outings together, bows in hand, sharing a fragment of Ishis lost world. Ishi showed Pope how to call game and how to understand the language of the birds and animals. He taught Pope how to still hunt for deer, while using the forest sounds, the wind, and the rising sun to the hunters advantage. And when their arrows missed game, Ishi would tell Pope the shot could easily have been made by the great Yana hunter, Chu-no-wa-yahi.

After three years in civilization, Ishi returned with Pope and company to the Yana homeland along Deer Creek. It was a brief and flickering bright spot in a life clouded with so much terror and loneliness. Pope wrote: We swam the streams together, hunted deer and small game, and at night sat under the stars by the campfire, where in a simple way we talked of old heroes, the worlds above us, and his theories of the life to come in the land of plenty, where the bounding deer and the mighty bear met the hunter with his strong bow and swift arrows.

Pope planned a return trip in the fall when he and Ishi could devote more time to hunting deer with their bows and arrows. But circumstance would cheat these brothers of the bow from their autumn hunt.

Ishi fell into ill health and later contracted tuberculosis. He quickly wilted before Popes eyes like a wild flower plucked by the roots. With Pope by his side, Ishi faded from the white mans world in the spring of 1916 when hills along Deer Creek once again bloomed with clover and the creek thundered with the splashes of mighty salmon.

With some acorn meal, dried venison, and his treasured bow and arrows by his side, Ishi was sent on his final long journey to the land of shadows. Pope wrote: His soul was that of a child, his mind that of a philosopher. With him there was no word for good-by. He said: You stay, I go. He has gone, and he hunts with his people. We stay, and he has left us the heritage of the bow.

From the last of the Yana to the unnamed bowmakers of generations to come the heritage lives on.

Bowyers Update

A SNAPSHOT IN TIME TWO DECADES LATER

Obviously, the one constant throughout life is change. Our paths can take some dramatic twists and turns over two decades. We grow wiser, older, lifes priorities shift, some of us move on to other professions, others to different places. A few have found their final place in recorded history.

Its been twenty years now since the traditional bowyers were interviewed in 1987. So it only seems right that the archery world should know in part what theyre up to these days and what changes are noteworthy in their lives.

One thing worth mentioning is a general observation about the traditional bowyers as a group. Studies show that most people change jobs every seven years. In todays volatile job market, it may be shorter. Thats why its a little surprising that so many of these bowyers are still immersed in their craft of turning wood and fiberglass into someone elses traditional archery dreams. Should we be surprised when a few pursue other things in life? Or should we more surprised that so many of them still make bows for a living? No, not if we truly understood what made them do it in the first place.

Like the original chapters in this book, the following updated paragraphs offer but a brief snapshot in time that give us a glimpse of the bowyers today. Unlike the first edition, youll find some Web site addresses here for the bowyers who have them and are still in business. Others have offered phone numbers for new business or contact information for past customers.