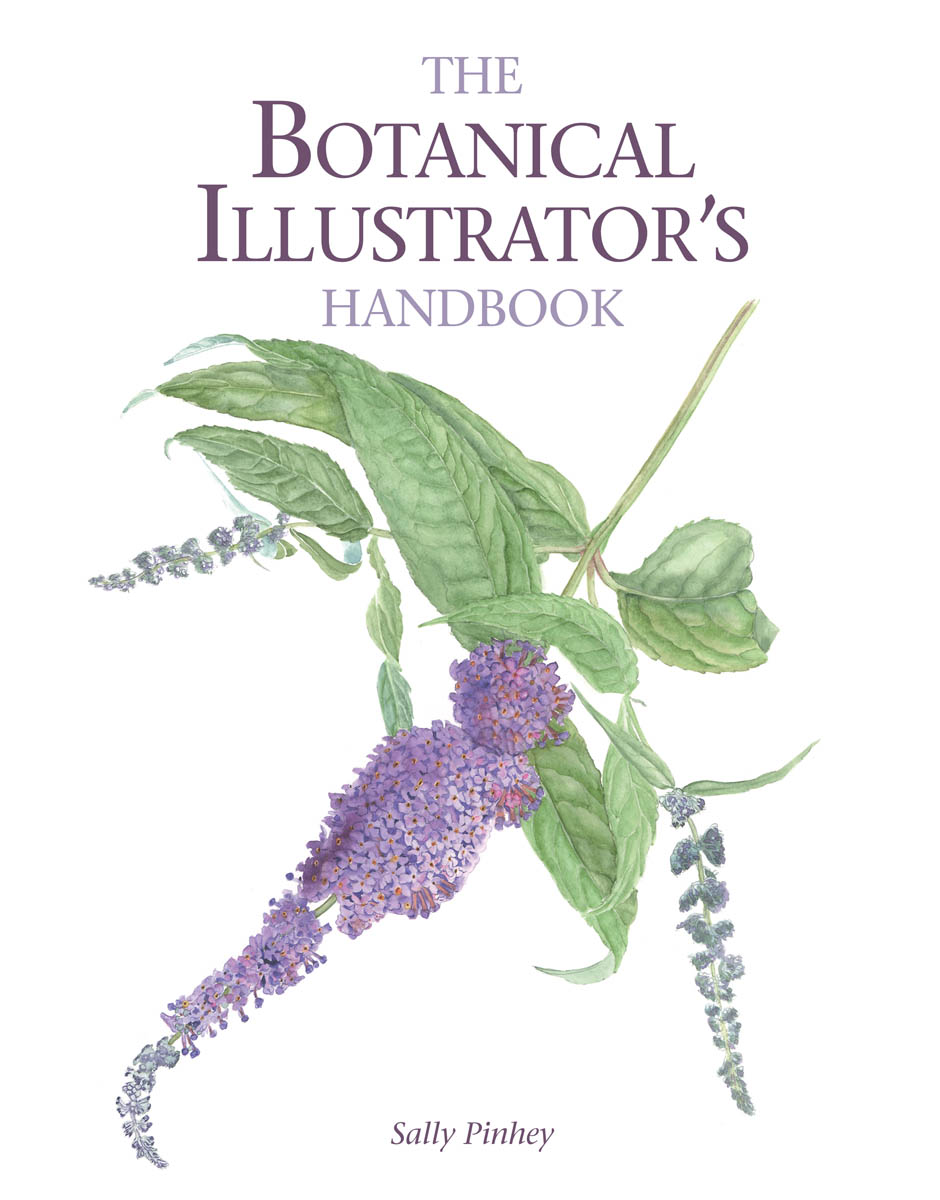

THE

B OTANICAL

I LLUSTRATORS

HANDBOOK

Sally Pinhey

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

Sally Pinhey 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 718 2

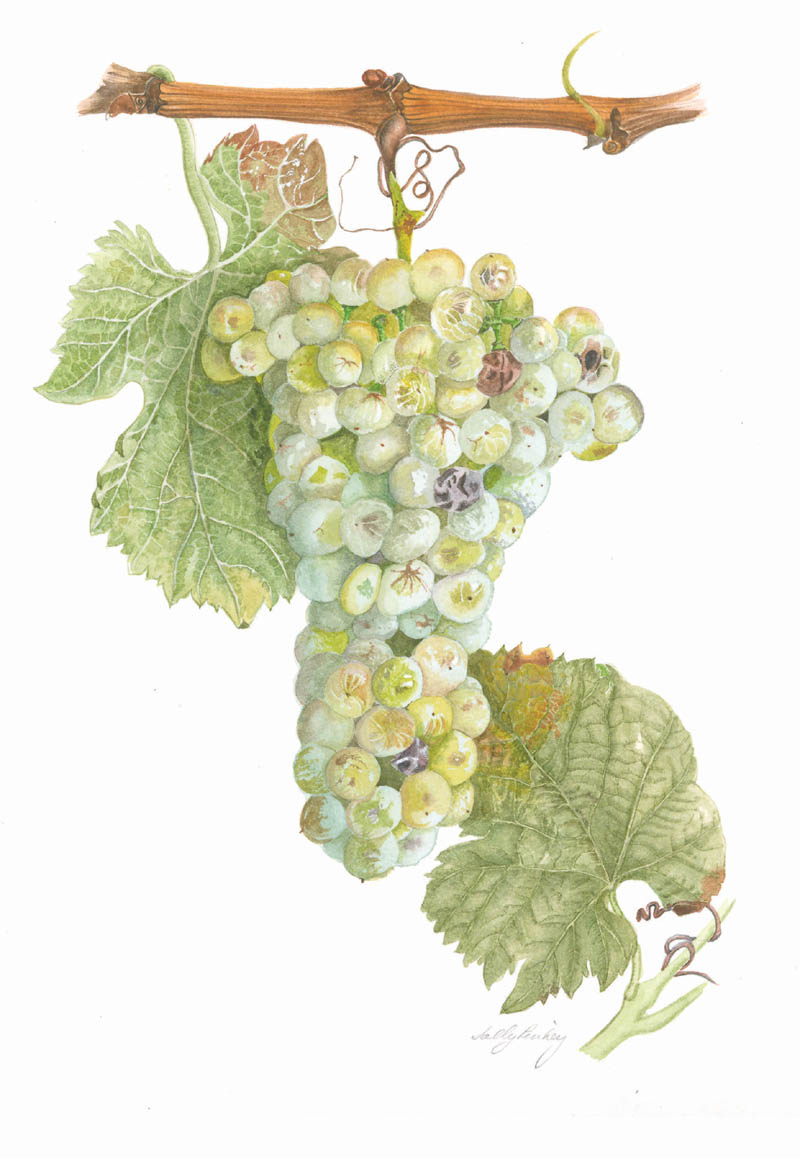

Frontispiece: Semillon grape.

Contents page: Parochetus communis.

Dedication

To all my students past and present who asked the questions.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the following people who have helped in producing this book. My husband Roger Pinhey for domestic forbearance, proof-reading and support; Dr Tom Cope, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, for checking the Latin; Simon Champion for technical advice and support; Paul Lunberg for computer help; Margaret Tebbs for her advice and support; Peter Berry for information on the Grenfell Medal; Rosemary Thompson of Rosemarys Brushes for information on brushes; Jim Patterson of 2 Rivers Paper for information on paper; Maggy Clarke, Nigel Hewish.

CONTENTS

Lychees.

INTRODUCTION

I dont know why you bother. I could do that in a hundredth of a second with my camera and You have wasted your paper are among the most deflating remarks that can be made to a botanical artist. Yet we do bother more and more. It is true that photography is a quicker and therefore much cheaper means of illustration. Cameras and digital enhancement also improve so fast that every year it is possible to achieve more with them. Yet the artists eye sees in a different way to the camera; the artist can analyse and isolate and show flower parts more clearly and with greater charm. The artist can also show stages of development and different seasons in one illustration so that it contains a more useful body of plant information.

While photography may have robbed botanical illustrators of some of their markets, it has also contributed to some of their techniques, helping to capture fleeting information on fragile structures. In the same way that improvements in optical instruments since the eighteenth century promoted botanical interest and discovery, so time-lapse photography has aided plant understanding for both scientists and illustrators. Where a painting has invested a flower with a glacial china-like stillness, however, I tend to think that the source photograph for it might have served equally well.

Go to any specialist botanical art exhibition in a city or country area and you will see a breath-taking selection of meticulously-painted flowers and plants. The strength and depth of botanical art skill in many countries are a source of wonder and delight. These artists have practised for years and reached the point where work of a high quality can be shown. For someone who teaches the subject, as I do, the popularity of this art form is most gratifying. The work on show gives little hint of any underlying weaknesses. Yet talk to the artists and ask why they chose that particular subject to paint and another view of the range of skills may emerge.

Naturally artists have their preferred subject matter. This may be influenced by personal attraction to colour or shape, academic interest, what grows in their garden, or by process of elimination what they choose not to paint because it is outside their comfort zone.

How often has an artist longed to paint a flower and found it has wilted before even the first drawing is complete? How many paintings on display show an uncharacteristically reduced amount of foliage? How many flowers are shown only face on or in profile to avoid the difficulty of a three-quarter view?

A love of plants is a given for botanical artists, and a love of colour will draw many to the blowsy garden varieties. Yet most plants are worthy of attention and description, and many are quite challenging in terms of composition and pictorial qualities.

While the botanists description and botanical key will serve to identify a plant, the old adage A picture is worth a thousand words holds true, especially if the picture is accurate. Botanical artists may yet hold the key to public plant awareness and conservation at a time when animals hold centre stage in research funding.

This book aims to deal with the difficulties that limit the choice of the artists subject. It should challenge and extend the perimeters of comfort zones, making the artist confident and versatile so that there is no plant that presents insuperable difficulties for botanical illustrating.

Recurring questions about the labelling and quality of papers, pencils and brushes are answered. |

The use of perspective in flower drawing and composition are addressed, so that the position of the plant on the paper need not be adjusted to cover for lack of foreshortening skills. |

Formulae for tackling complex structures are shown. |

Ideas for coping with short lived (ephemeral) plants are given together with when to use a camera, the purpose of sketches and plant care. |

Painting in the field, and tricky details such as hairs are addressed. |

The use and knowledge of botanical terms and Latin names are also explained, and what we can pick and if we can copy. |

Finally, there is a chapter on self-promotion, copyright care and mounting an exhibition. Some chapters are packed with straight information, others with personal experience and advice. The difference should be clear. |

Bananas.

Much of the technique and comment here applies equally to all media, though the reader will notice the strong bias towards watercolour techniques. The main difference in approach is that watercolour is always painted from light to dark and for other media such as coloured pencil and acrylics the reverse is the case and highlights can be superimposed. I make no apology for thinking mainly in terms of watercolour. It is my speciality. For botanical illustration it is a tried and tested medium with all the versatility and delicacy necessary for our beautiful subjects. Nevertheless many of the concepts in the following chapters are applicable to most media.

Where standard English vocabulary describes a plant part or function perfectly well, it is used. Where special vocabulary is required, it is explained. The glossary covers both botanical terms and Latin names.