Search Patterns

Peter Morville

Jeffery Callender

Copyright 2010 Peter Morville and Jeff Callender

O'Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (.

Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O'Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O'Reilly Media, Inc. Search Patterns , the image of a white-barred charaxes, and related trade dress are trademarks of O'Reilly Media, Inc.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O'Reilly Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps.

While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and authors assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

O'Reilly Media

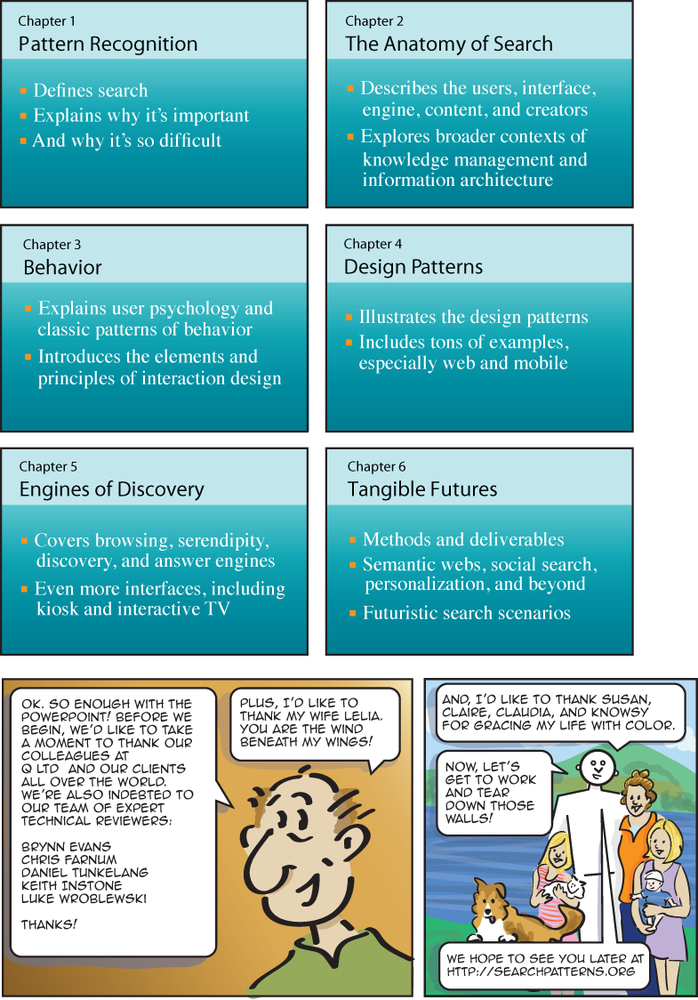

Chapter 1. Pattern Recognition

" The future isn't just unwrittenit's unsearched ".

Bruce Sterling

In astronomy, averted vision is the art of seeing distant objects by looking to their periphery. It works by shifting responsibility from cones, which sense color and fine detail, to rods, which detect motion and help us to juggle, play chess, and see in the dark. This form of peripheral vision can be practiced. Observers often report a gain of three to four magnitudes. It's a powerful reminder that sometimes we must look away to see.

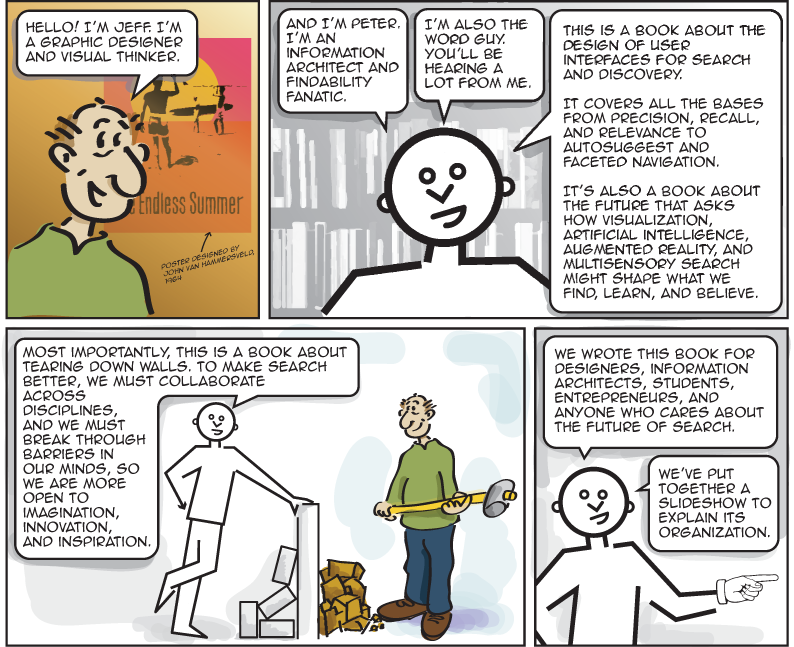

This book will test our ability to juggle multiple visions of search and discovery. We will look to the center by describing a pattern language for search that explains user psychology and behavior, embraces emerging technologies and rich interaction models, and illustrates repeatable solutions to common problems. We will explore the edges by studying cool tools that help users ask, browse, learn, share, visualize, and understand.

This juggling act is necessary if we are to pursue both incremental improvement and radical innovation. In today's world of intense competition and rapid change, both are essential. Search applications demand an obsessive attention to detail. Simple, fast, and relevant don't come easy. Success requires extraordinary focus in research, design, and engineering, yet you can't test and tweak your way from Google to Twitter. Time and again, the future of search is invented beyond the borders of its category.

And, search has a future. Search is not a solved problem. Indeed, search is a wicked problem of terrific consequence. As the choice of first resort for many users and tasks, search is a defining element of the user experience. It changes the way we find everything from answers, articles, and advertising to products, people, and places. It shapes how we learn and what we believe. It informs and influences our decisions, and it flows into every nook and cranny. Search thrives within and across myriad contexts and channels. Web, e-commerce, enterprise, desktop, mobile, social, and real time are just a few of its classifications. Search is among the biggest, baddest, most disruptive innovations around. It's a source of entrepreneurial insight, competitive advantage, and impossible wealth.

Unfortunately, it's also the source of endless frustration. Search is the worst usability problem on the Web. It's held that title for many years. We find too many results or too few, and most regular folks don't know where to search, or how. From enterprise to e-commerce, user needs and business goals are obstructed by failures in findability. And the news doesn't improve when you change the channel. Mobile search is a mess, kiosks are worse, and interactive television remains the lonely domain of the early adopter. Your average couch potato isn't quite ready to trade his remote control for a search box.

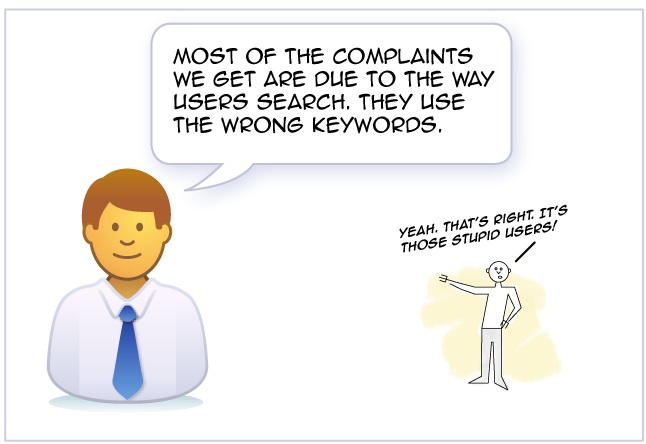

Figure 1-1. A manager explains why search stinks

Of course, pundits claim we'll solve search soon with artificial intelligence, information visualization, personalization, and the Semantic Web, but this fabled future never arrives. Search remains as noisy and irregular as language and communication. Vendors hawk their wares to IT executives who understand business and technology but turn a blind eye to user experience. Content stakeholders perfect their publishing workflow only to bury their crown jewels behind firewalls and within tightly controlled information silos. Design teams work hard to make search simple, but lack the skills and tools to ensure relevance and speed. Once in a while, the stars do align and real solutions emerge, but in most organizations and applications today, bad search remains an inconvenient truth.

And even when search works well, it can always be improved. Even Google is only good enough until something better comes along. In search, innovation is a forced move. It's not easy, but it's not impossible. It is important. And that is the reason for this book. We want to make search better. Or, to be more precise, we want to inspire you to make search better. But first, we had better define what it is that we seek to improve.

Understanding Search

The way we define a problem or frame a question shapes how we and our colleagues understand, answer, and act. An overly narrow formulation leads to tunnel vision, and we're oblivious to all but the obvious. But stray too far from the center, and we lose our focus while trying to boil the ocean. The best strategy is to avert and revert, juggling ideas, patterns, gaps, and oddballs in the periphery without losing sight of the goal.

The Box

In search, the first ball in the air is a box. It's the iconic symbol of search and a great place to start. Enter a keyword or two, and you're good to go.

Figure 1-2. The iconic search box

The box comes in all colors, shapes, and sizes. It sports a variety of buttons and labels. It appears as a feature of sites, browsers, applications, and operating systems, and it's found across channels and within all forms of interactive media. The box has grown so familiar it now lives in our heads like Plato's perfect circle. We recognize it as a box, even when it's not.

Figure 1-3. When is a box not a box?

Of course, each box has its secrets. How can I search? What's being searched? Its affordance tells us little about language and scope. Are we querying the text of Twitter or the metadata of music? And can we simply enter keywords or must we speak Boolean? The answers are revealed by context and experience. On Flickr, we know we seek images, but we must learn how and why to query by tag and filter by interestingness.