Text copyright 2014 by Hiro Sone and Lissa Doumani.

Photographs copyright 2014 by Antonis Achilleos.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4521-3039-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 978-1-4521-0710-3 (hc)

Designed by Vanessa Dina

Prop styling by Christine Wolheim

Food styling by Hiro Sone and Lissa Doumani

Typesetting by DC Type

The authors wish to thank Susan Naderi Johnston for her help with the What to Drink with Sushi text.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Acknowledgments

Having grown up on a small rice farm, I appreciate the hard work that goes into growing rice. Long and backbreaking hours are spent planting the rice, harvesting it, and hoping the weather does not destroy the crop. Without rice farmers we would not have this critical ingredient in sushi-making.

Hiro

We would like to first thank the fishermen who go out each and every daytirelesslyto bring back the bounty of the sea that allows us to make such beautiful sushi. Theirs is a hard life with limited rewards for them but boundless rewards for all of us who consume their fish. We hope that by working together we can keep their profession viable for them and for the oceans they draw from.

A big thank you to Tom Worthington of Monterey Fish, who kept us on track with information and tirelessly answered all of our questionsand there are so many factors to consider when writing about fish, from availability to nomenclature! He has been providing us with the highest quality fish since we opened our first restaurant, Terra.

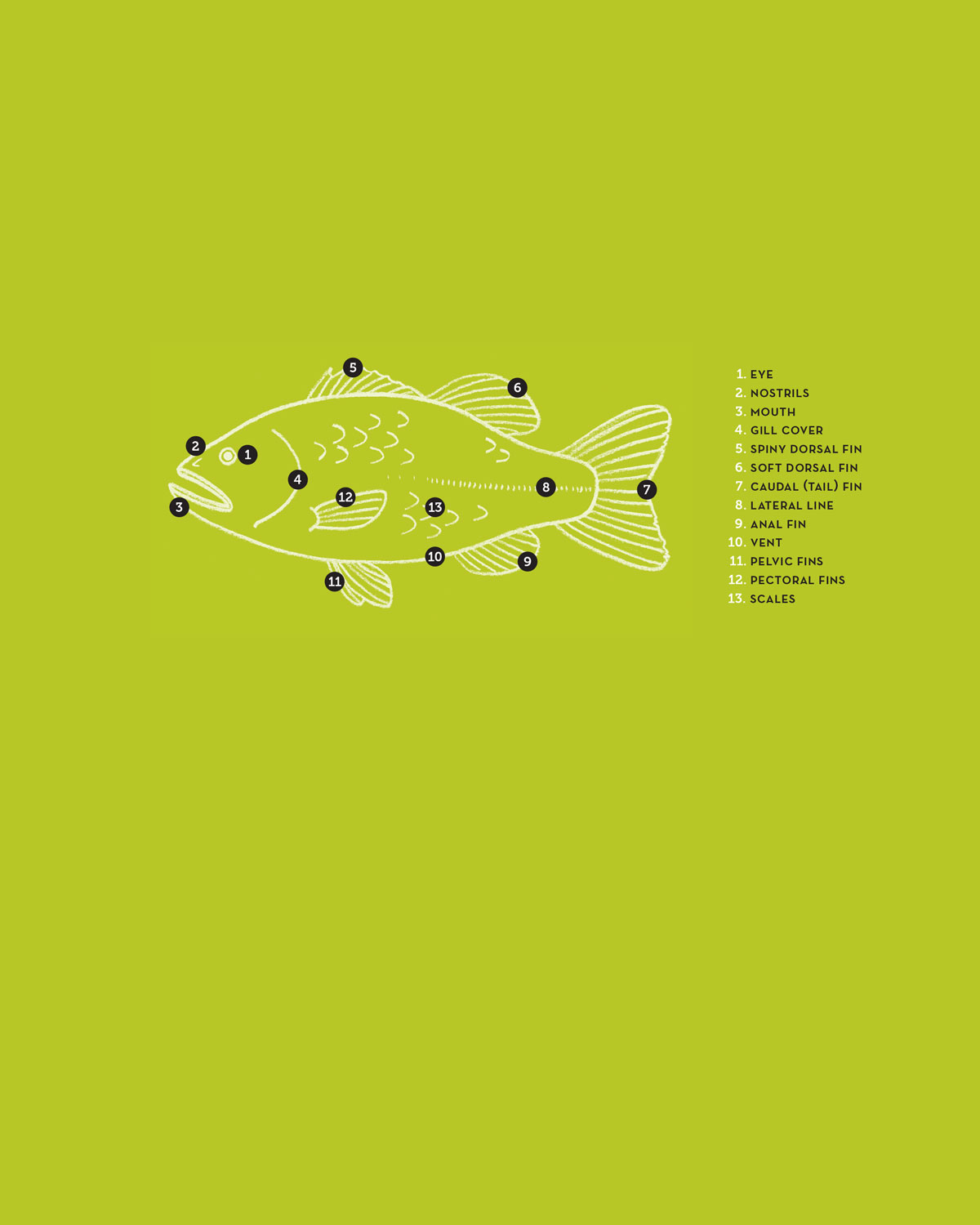

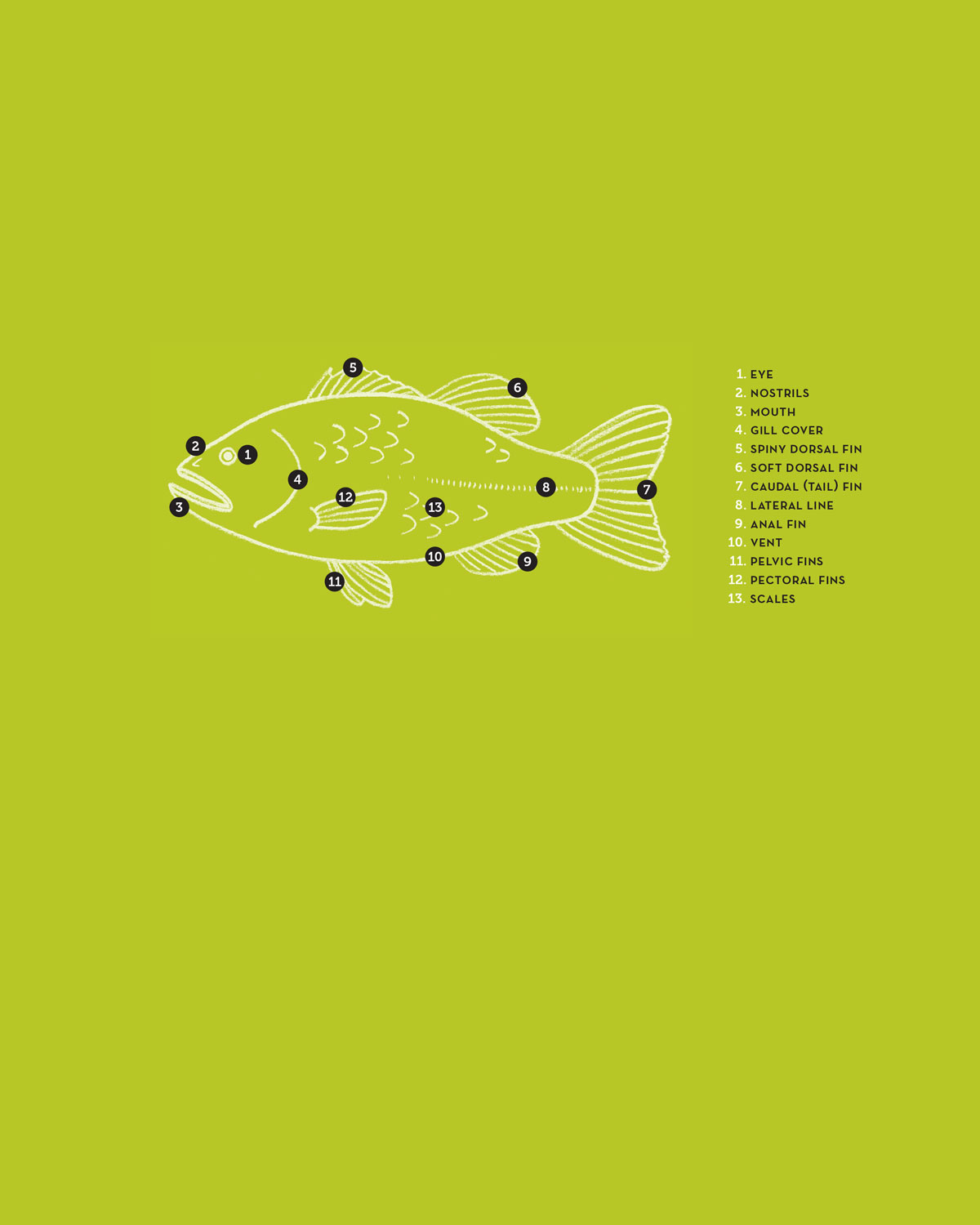

Thank you to Lorena Jones, who had the crazy notion to ask a couple of nonsushi chefs to create a book that could be understood by cooks of all levels, and for the patience she showed when we went so deeply into understanding the anatomy of fish and how to break them down.

Thanks also to Sarah Billingsley, who edited a book that was so very technical on a subject that was not familiar to her. She showed angelic patience when we came back time and time again to correct the small details that mean so much to us. Many times we all ended up laughing at where things got crossed up.

Vanessa Dina was able to interpret our vision so beautifully; her patience and gentle guidance has brought together a stunning book. Thank you also to the rest of the team at Chronicle Books.

To the sushi lovers: Yes, you. We are one with you and love the passion and exuberance you have for sushi. You have helped sushi become one of the most important cuisines in the world. To feed our passion, lets think about sustainability and respect the land and the oceans we are a part of.

Lissa and Hiro

CONTENTS

Introduction

Sushi. When you hear that word, be honest; dont you immediately ask yourself, Where can I go to eat sushi right now? Fortunately, sushi is widely available these days, especially in larger cities. But even in smaller towns, you are likely to find at least a few Japanese restaurants, and most of them will have a couple of sushi items on the menu.

This is a dramatic change from just thirty years ago when sushi was popular only among travelers and cooks and diners interested in ethnic cuisines. Now, you can find sushi in your local grocery store, something that you dont even see in small markets in Japan. In bigger U.S. cities, you can usually find a Japanese restaurant within a square block or two of any commercial district. Upscale Western-style eateries have started to put sashimi on their menus, though most of them are not yet ready to add rice to the mix by trying to serve sushi. At Ame, we fall into this category. One section of our menu is devoted to sashimi, though it is not at all traditionally prepared but instead influenced by the worlds cuisines.

We go out for sushi and sashimi at least once a week but usually twice. It is what we crave and what leaves us feeling well afterward. We are traditionalists, preferring pristine fish and a small accompaniment when appropriate, though we do enjoy watching the twists that sushi chefs have been putting on traditional sushi varieties. These culinary masters have a natural curiosity that makes them want to grow and create. Some new ideas work; other times, too many ingredients are used and the fish gets lost. Not surprisingly, this happens most frequently with sushi rolls.

Although, nowadays, diners in the United States can choose from many Japanese restaurants, big and small, plain and fancy, such abundance is relatively recent. In the years preceding World War II, Japanese eating establishments were primarily simple spots located in Japanese American neighborhoods in towns in Hawaii and on the West Coast. In the 1930s, New York boasted a handful of restaurants that catered to cosmopolitan diners who enjoyed tempura, teriyaki, and other unchallenging fare, but not sushi or sashimi. It was only after the war that Japanese restaurants began appearing in greater numbers, and it was not until the late 1950s that sushi was on the menu.

Originally, only a handful of rolls (maki-zushi) were served: tuna, cucumber, marinated kampy (dried gourd strips), and futomaki (a thicker roll usually without raw fish). Back then (and still at some places today), sushi was served on a large wooden boat. It is not clear why a boat was used, unless it was to telegraph subconsciously that the fish was fresh from the sea. The now-famous California roll was invented in the 1960s at Tokyo Kaikan, a Japanese restaurant in downtown Los Angeles. The chef was trying to create sushi like he had made in Japan but using ingredients available in his new home. Crab was plentiful but it needed something rich to complement it, so he tried avocado. The California roll was not an instant success, but it eventually developed a following, and it illustrates how sushi chefs worked with what was available.

California rolls did not make it to Japan until the 1980s, and even then they appeared at only a few restaurants. Sushi chefs at some establishments in the United States are purists and still refuse to make them. But most people in America enjoy a balance between traditional and contemporary sushi, and even the rolls that we consider over the top with ingredients have their own following.

Almost all cultures include raw fish at their table. For example, the Italians have pesce crudo, the French poisson cru, and the Peruvians ceviche. During our travels outside of the United States, we have seen many versions of sushi. At a popular sushi bar in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, the offerings maintain a strong Japanese tradition but include traditional Mexican flavors such as chiles and occasionally an accompanying salsa.

In San Sebastin, Spain, a chef served us Spanish molecular cuisineinfluenced sushi, marking the first time we experienced soy sauce foam.

Peru already had a long history of eating raw fish when Japanese immigrants began arriving at the beginning of the twentieth century, so today Peruvian cuisine carries a prominent Japanese culinary mark, and local menus often describe dishes as being

Next page