DEDICATION

To DeVeau, whose name should be next to mine on the cover of this book,

and Harlo, who keeps my head in the right place. Love you both.

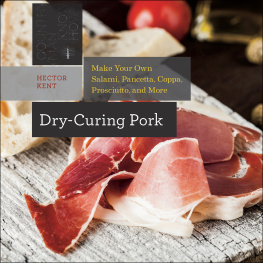

My wife and I were lucky to be raised in families that valued growing or sourcing food locally. After we moved away from these homes, we were always happy to purchase the wares of local growers and producers near our home in Oregon. As teachers, we prioritized the ability to start our summer adventures on the first day of vacation over growing all our own provisions. On one of our shopping trips into Portland to a favorite butcher, we noticed as we purchased a piece of beef that everything in the display case was locally produced, except the salami. This was in the days before Olympic Provisions and Chop Butchery began selling their products, and as we drove home we expressed our surprise that the only available salami, while tasty, was coming from a major producer from over 500 miles away. Even more concerning, we had no idea where the pork had originated.

Our home at the time was on the desert end of the Columbia River Gorge. We looked out on the barges, trains, and windsurfers while enjoying the plentiful sunshine and poison oak that eluded the western half of the state. We spent hundreds of hours roaming the hills above the river walking through the wildflowers, windblown oak groves, and rolling hills of yellow grass that surrounded our home. One day, as we looked around at the blanket of acorns around us, we thought: Why not raise our own pigs? Why not make our own salami?

We continued the conversation, and over the next few months we came to realize that many people were thinking the same thingincluding our favorite butchers. But it was our friends down the street, Quin and Dave, who get the credit for getting us started on this dry-cured adventure. Several weeks after mentioning our interest in pork one night over dinner, we returned from an early-summer adventure to discover that they had purchased two piglets for our families to share. The animals were now happily roaming their yard and fattening up on acorns.

Acorn-fed pork is legendary, argued to be the best in the world, so as we cut into our first dry-cured ham, we had thoughts of a delicate prosciutto on the brain. We quickly became aware of the hard, salty reality. Dry-curing is an art and a science, and we knew we needed guidancethe random recipe off the Internet didnt do a pig justice. I turned to the small number of resources responsible for introducing thousands of people to dry-curingCharcuterie by Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn, and Cooking by Hand by Paul Bertolli. I read them cover-to-cover, learning everything I could, and we started practicingjust a shoulder now and then. It was a couple years before we took on a whole pig again.

Through this learning process, I assumed I could find the necessary teaching materials to continue progressing. I had started homebrewing a few years earlier, and there were countless books and Internet resources availablenot to mention the whole craft-brewing culture springing up around the developments of homebrewers. I assumed things would be similar in the world of dry-curing, but I quickly realized that the same resources didnt exist. While I could find the occasional step-by-step instructions for making a specific product based in vaguely Italian traditions, there was no consistency. This was adequate at first, but Im a biology teacher, and I wanted the actual science. I wanted to know which variables I should be paying attention to, and how these variables could be adjusted and manipulated to perfect my final product.

At the same time, like many people who enter the world of dry-curing, I wanted to create authentic Italian dry-cured meats. As I pursued this goal, I realized that imitation of Italian products and methods is a great teaching tool, but imitation doesnt lead to authenticity. Every region of Italy, not to mention every region of the Mediterranean in general, has its own dry-curing style. The magnitude of the diversity was deeply confusing. What Ive come to realize is that since people embraced the flavors and conditions of their homes in creating their dry cures, imitation wasnt actually a priority.

Theres nothing more authentic than buying a pig from the woman down the street, cutting it up on a folding table in your yard, flavoring it with dried herbs from your garden, and hanging the cuts in your shed. The trick was finding the background knowledge that would allow me to perfect the combination of my ingredients as opposed to copying a technique used on another continent. This search for knowledge introduced me to the research of legendary Spanish meat scientist Fidel Toldra. I realized the information I sought did exist, but it would require a journey into the world of European meat science.

Fast-forward a few years, and the result is what you have in your hands. Ive filtered through thousands of pages of research and data on dry-cured meats and pieced together the critical aspects in the pages of this book.

At its core, this is meant to be a book that teaches you so that at some point you wont need it anymore. In it, I present a basic process you can follow step-by-step, but also give you the science behind the process, so you can dry-cure anything, Italian or not. If you dont have access to an Italian butcher, it doesnt matteryou can dry-cure any meat, whether or not its exactly how the Italians do it. True authenticity will be attained by perfecting the process of bringing together all your own variables, in a way I cant show you, because those variables are unique to your place.

Finally, I never set out for dry-curing to become a major part of our lives. Weve now left Oregon for Vermont, and unexpectedly every autumn, as the last leaves fall off the maples, our extended family gathers and we begin the process of paying our respects to the recently killed pigs. We do this not with band saws to cut pork chops destined to become lost in the depths of the freezer, but by carefully segmenting whole pieces of beautifully marbled, dark-red muscles into their natural forms. We continue the ode to pork by salting, drying, and finally thinly slicing meat onto a plate with a little cracked pepper and lemon.

You will find an unexpected and welcome revival of old methodsand I dont mean old methods for our family, because we dont come from a tradition of dry-curing. What started as we walked through the oaks and wildflowers has developed into a celebration of family and food. The grill is hot so we can snack on the bones, a keg of homebrewed fresh-hop beer is on tap, and we know that in a few months we will cut into a coppa that has never traveled more than 500 feet from the grove of trees where the pig spent his days. If Im lucky, Ill get a taste of the flavors of summertime and home.

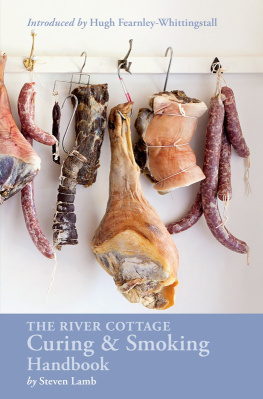

The term cured meat primarily refers to meats that have been modified through the application of either salt, sugar, or smoke.

Next page