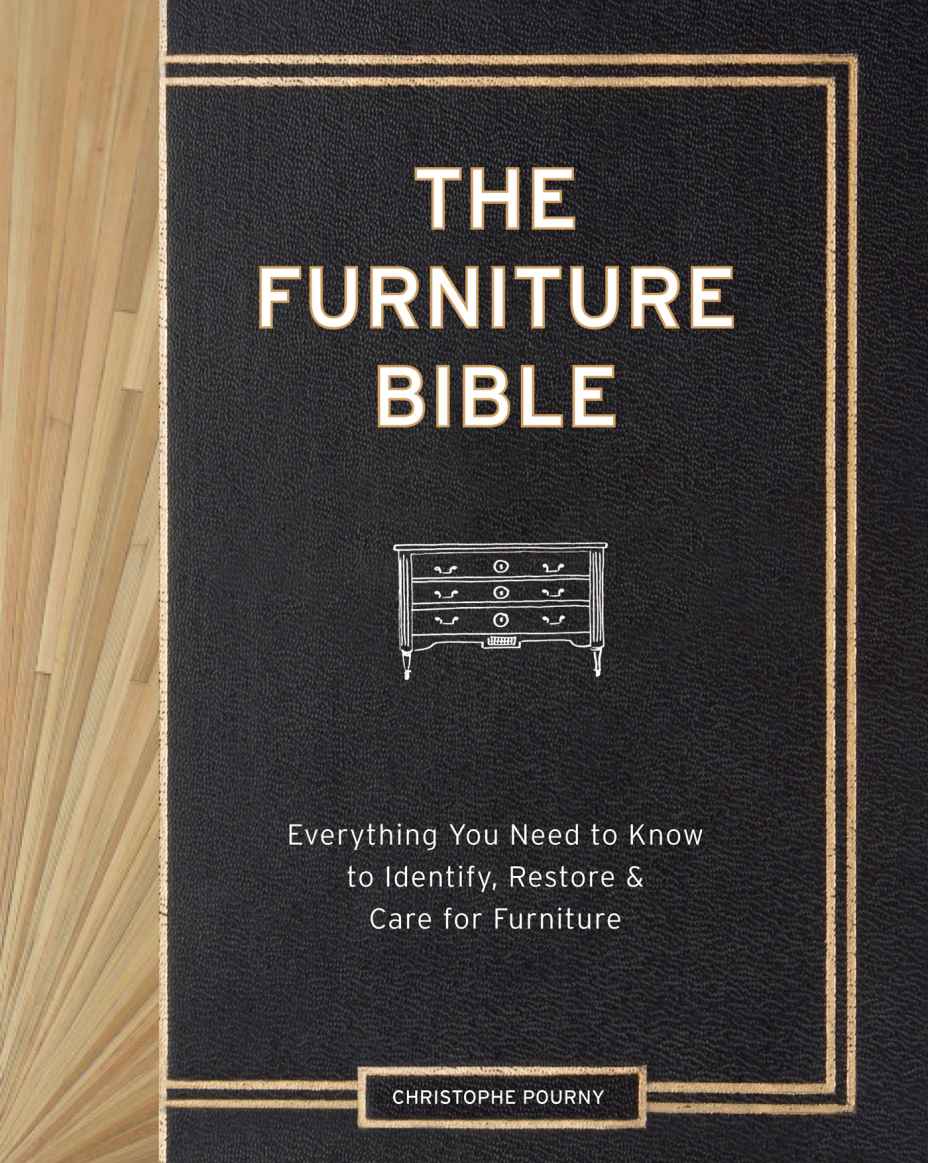

The Furniture Bible

Christophe Pourny

with Jen Renzi

foreword by Martha Stewart

photographs by James Wade

illustrations by Christophe Pourny

To my mother, Arlette Pourny

Contents

Foreword

Christophe Pourny restores, transforms, fixes, preserves, and teaches in this, his first book, The Furniture Bible. He also encourages us, the homeowner, the decorator, the collector, the furniture buyer, to appreciate, to discriminate, to determine, and to choose furniture that might have a place in our life, a spot in our home, a future as a collectible or as an investment.

This is a very useful and important book for anyone who owns furnitureantique, modern, or newor anyone who plans to fix or restore it. It is encyclopedic in its scope, and unusual in its clear, straightforward, and understandable approach to all aspects of a very large subject matter. Christophe is extremely knowledgeable, and with extreme clarity he has demystified a subject heretofore covered only in part in many instructional manuals or much simpler DIY books. I, personally, welcome this book into my library, and I know it will be used not only by me, but by anyone who dusts and polishes, repairs, or restores.

Chapter by chapter, the history of furnitureits construction, its components, its finishes, and its decorationis written about and illustrated with photographs and charming drawings. The chapter on how furniture is made teaches us how and why certain woods are used for the bottoms of drawers, for the fronts of chests, and for the legs of chairs. The Finishing School chapter is extremely valuable in helping us understand the materials and the methods by which furniture makers have evolved the various surfaces we lay our hands upon or dust with a soft rag. The chapter on techniques is illuminating in its references and step-by-step instructions, not just about the woods employed in a piece of furniture, but also for the metals and other materials used in the beautification of certain pieces, or for practical utilitarian reasons.

Congratulations, Christophe Pourny! You have created for all of us, laymen, artisans, and collectors alike, a compelling reason to look at our own furniture in a new way, to appreciate fine craftsmanship and understand what is good, what is better, and what is best. And, above all, you have given us the impetus to repair, restore, and preserve the legacy of past makers so that those in the future will have great examples with which they can be inspired.

Martha Stewart, 2014

Introduction

Every artisan has in his brush, his pencil, his tool, not only what links his task to his mind but also to his memory. A move that may appear spontaneous is actually ten years in the making, thirty maybe. In art, everything is knowledge, labor, patience and what comes in an instant has taken years to blossom.

French architect Fernand Pouillon (19121986)

Coming from a long line of artisans, I was weaned on the antiques business. When I was five, my parents opened their first antiques store, in the Var region of the South of France. At that time, it was still possible to buy and resell the contents of an entire castle. Growing up in the village of Fayence, my sisters and I performed puppet shows amid the giant carved armoires residing in the courtyard of our fathers atelier. His studio was in an 18th-century stone barn built to house sheep on their annual pilgrimage to higher feeding grounds, up in the Alps. Where livestock once snoozed, furniture pieces of every style and period were piled atop one another, arranged in pyramids of wood, dark and glowing like an amber fire. The interior was very dark, the windows smallnatural protection against the Provenal sunbut the space was also beautiful and magical, perfumed with beeswax and the musk of centuries of use.

I trained under my father from an early age, first fetching tools and stains for his artisans and finally learning to use these items to cut, join, sand, and so on. More than once I swore Id never touch another piece of furniture! (Using slivers of glass to strip off old varnish will do that to a person.) But I eventually succumbed to my fathers love of wood. I discovered how various species responded differently to our care. I learned to evaluate trueness, texture, and grain even as I climbed the olive trees around our house. In a language passed down through the generations, my father taught me that oak was good for certain applications and elm for others, that Cuban mahogany was very rare and French walnut very versatile. I came to understand that wood is the craftsmans medium, like canvas for an artist or paper for a writer, and that one piece can be coaxed into an endless variety of colors, textures, and shapes. Eventually, I discovered how these finishes interacted with the lines of furniture to create beautyand how this beauty informs the way we feel about a table, a room, or even a house.

After university, I moved to Paris to apprentice with my uncle, Pierre Madel, who had a shop on rue Jacob. He was a legend, and his loyal clientele extended from Saint-Tropez to San Francisco. There I met all the artisans and art dealers who made Paris the heart of the antiques world. It was easy to get swept up in the glamour and romance of it all. Nevertheless, I became restless, and I felt New York calling my name. I moved to Manhattan in my late twenties, eventually opening my own studio in Brooklyn. My days are now spent regilding Louis XVI bergres, refreshing the French polish of 18th-century dining tables, or working magic on timeworn straw marquetry surfaces. Restoring rare antiques to their original condition in the same manner that my father instructed me back in Fayence became my life in New York. Just as important, I also transform less distinguished pieces into stunners via a completely new and often unexpected finish. My passion for and deep understanding of historical methods have taught me how to take creative license when a piece merits it.

Sadly, these techniques that are my lifeblood are also a dying art these days, in the era of spray-on one-coat varnishes. What happened to traditional methods of wood finishing, the techniques of my father and grandfather and other highly specialized ateliers? What used to be common knowledge is now the purview of a few aging artisans, surrounded in their studios by bottles labeled with names as exotic as Persian perfumes. Even experienced woodworkers may not know the secret behind the perfect wax finish unless their library is filled with dusty early-19th-century French guides. So little of this old-world knowledge ever crossed the pond in the first place, and scholastic programs that teach refinishing are an endangered breed. One of the last and best, at New Yorks Fashion Institute of Technology, was recently canceled.

Ironically, this body of knowledge is also being threatened by a misguided fetishization of the old at the expense of all else. Cultural phenomena like