Copyright

Copyright 2010 by Bookmagic, LLC.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except of brief quotations in critical reviews and articles.

Home Production of Quality Meats and Sausages

Stanley Marianski, Adam Marianski

ISBN: 978-0-9836973-6-7

Bookmagic, LLC.

www.bookmagic.com

Introduction

Books about making sausages can be divided into two groups. Books that are written by professional sausage makers and books that are written by cooking enthusiasts or restaurant chefs. The second group deals mainly with fresh sausages which are embarrassingly simple to make. They are loaded with recipes but do not explain the rules for making successful products. Those are basically cookbooks where a sausage becomes an ingredient of the meal.

There are just a few books that cover not only the subject of making fresh sausages, but add information on making smoked products, blood sausages, head cheeses, liver sausages and even fermented sausages. Not surprisingly, these books are written by the professional sausage makers or advanced hobbyists who possess a vast amount of knowledge not only about making sausages, but about meat science as well.

The purpose of this work is to build the bridge between meat science and a typical hobbyist. To make those technical terms simple and easy to follow and to build a solid foundation for making different meat products. Many traditional recipes are listed but we want the reader to think of them as educational material to study.

Although recipes play an important role in these products, it is the process that ultimately affects the sausage quality. Not knowing the basic rules for making liver sausages makes the reader totally dependent on a particular recipe which in many cases is of unknown value. This leaves him with little understanding of the underlying process and in most cases he will be afraid to experiment and improvise making sausages by introducing his own ideas. He should also realize that as long as he follows a few basic rules he can come up with dozens of his own recipes and his sausages will be not only professionally made, but also custom tailored to his own preferences. Information in the book is based on American standards for making safe products and they are cited where applicable.

There is a collection of 172 recipes from all over the world which were chosen for their originality and historical value. They carry an enormous value as a study material and as a valuable resource on making meat products and sausages. It should be stressed here that we dont want the reader to copy the recipes only. We want him to understand the sausage making process and we want him to create his own recipes. We want him to be the sausage maker.

Stanley Marianski

Chapter 1 - Principles of Meat Science

Meat is composed of:

- water - 75%

- protein - 20%

- fat (varies greatly) - 3%

- sugar (glycogen, glucose) - 1%

- vitamins and minerals - 1%

Different animals or even meat cuts from the same animal exhibit different proportions of above components and this depends on the animals physical activity and type of diet. Those factors not only affect animal meats components, but the color of the meat as well.

Meat contains about 75% of water but fat contains only 10-15%. This implies that a fatty meat will lose moisture faster as it has less moisture to begin with, the fact which is important when making air dried or slow fermented products. As the animal matures, it usually increases in fatness, which causes a proportional loss of water.

Meat Aging

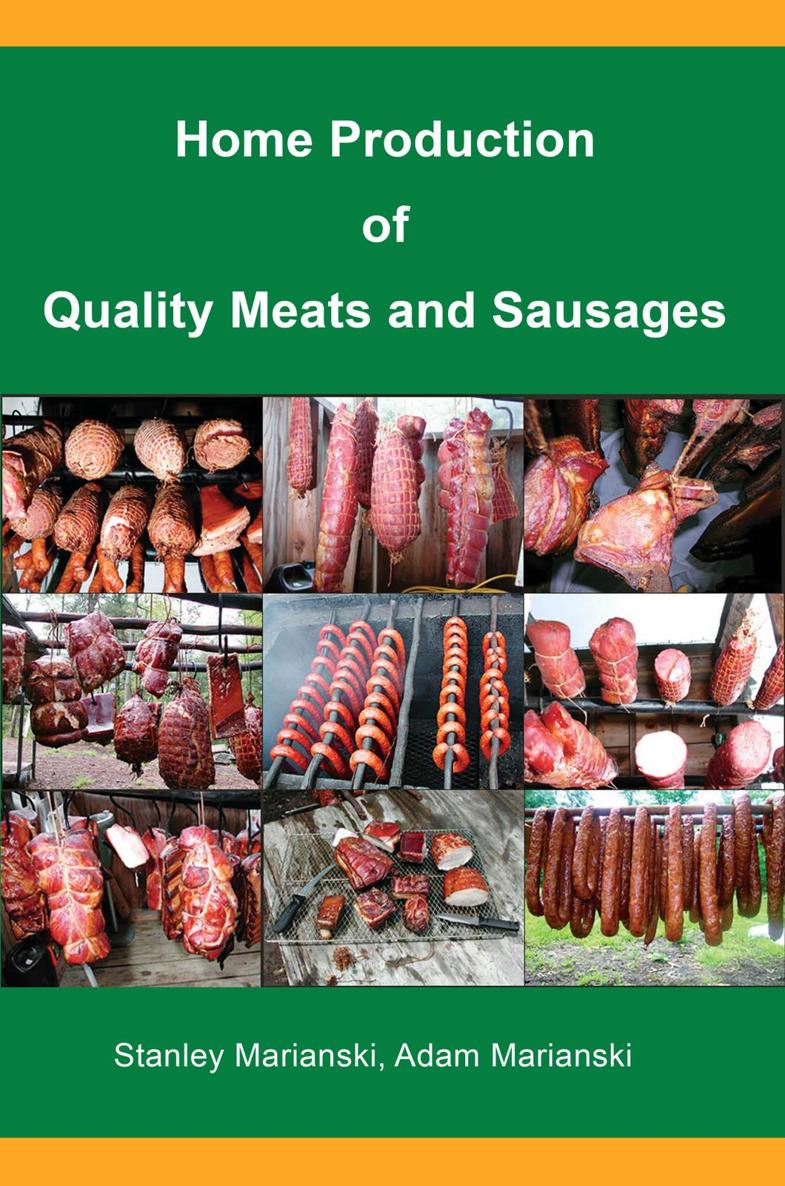

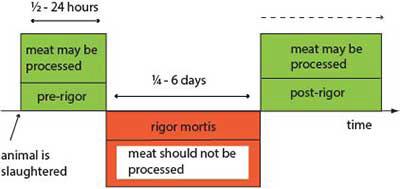

When an animal dies, the oxygen stops flowing and many reactions take place inside. For a few hours the meat remains relaxed and may still be processed or cooked. Then muscles contract and the meat stiffens which is known as the rigor mortis stage. During that stage, which lasts differently for different animals, the meat should not be processed or cooked as the resulting product will be tough. Meat stock prepared from meats still in the rigor mortis stage is cloudy and has poor flavor. When this stage ends, the meat enters rigor stage and is kept in a cooler. In time it becomes tender again and is ready for processing. It is widely accepted that this happens due to the changes in the protein structure. The length of rigor mortis or rigor stage directly depends on temperature. The higher the temperature, the shorter the stages and vice versa. Make note that aging meat at high temperature will help bacteria to grow and will adversely affect meats shelf keeping qualities.

Fig. 1.1. Effect of rigor mortis.

Times for onset and resolution of rigor |

Time to onset of rigor | Time for resolution of rigor |

Cattle | 12 - 24 hours | 2 - 10 days |

Pigs | 6 - 12 hours | 1 - 2 days |

Lamb | 7 - 8 hours | 1 day |

Turkey | - 2 hours | 6 - 24 hours |

Chicken | - 1 hour | 4 - 6 hours |

Rabbit | 12 - 20 hours | 2 - 7 days |

Venison | 24 - 36 hours | 6 - 14 days |

Looking at the above data, it becomes conclusive that the aging process is more important for animals which are older at the slaughter time (cattle, venison). Warm meat of a freshly slaughtered animal exhibits the highest quality and juiciness. Unfortunately there is a very narrow window of opportunity for processing it. The slaughter house and the meat plant must be located within the same building to be effective. Meat that we buy in a supermarket has already been aged by a packing house. If an animal carcass is cooled too rapidly (below 50 F, 10 C) before the onset of the rigor (within 10 hours), the muscles may contract which results in tough meat when cooked. This is known as cold shortening. To prevent this the carcass is kept at room temperature for some hours to accelerate rigor and then aged at between 30-41 F, (-1 - 5 C).

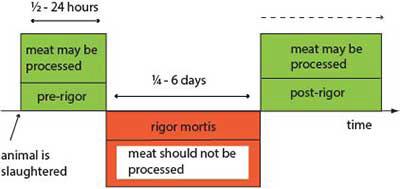

pH of the meat

When an animal is alive the pH (acidity) value of its meat is around 7.0 (neutral point). After the slaughter and bleeding, the oxygen supply is interrupted and enzymes start converting glycogen (meat sugar) into lactic acid. This lowers the pH (increases acidity) of the meat and the process is known as glycolysis. This drop is as follows:

- Beef - pH of 5.4 to 5.7 at 18-24 hours after slaughter.

- Pork - pH of 5.4 to 5.8 at 6-10 hours after slaughter.

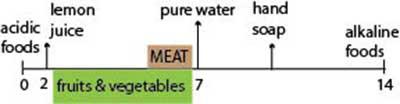

The concept of pH is also covered in Chapter 20 - Fermented Sausages. Understanding pH of meat is quite important as it allows us to classify meats by the pH and to predict how much water a particular type can hold. If you drink lemon juice or vinegar you know the acidic taste of it. Gentle foods such as milk will be found on the opposite end of the scale.

Fig. 1.2 General pH scale.

How fast and low pH drops depends on the conditions that the animal was submitted to during transport and before slaughter. The factors that affect meat pH are genetics, pre-slaughter stress and post-slaughter handling.

Next page