New York

To our customers and friends, past, present, and future.

Contents

Foreword

by Annaliese Griffin, editor in chief, Brooklyn Based

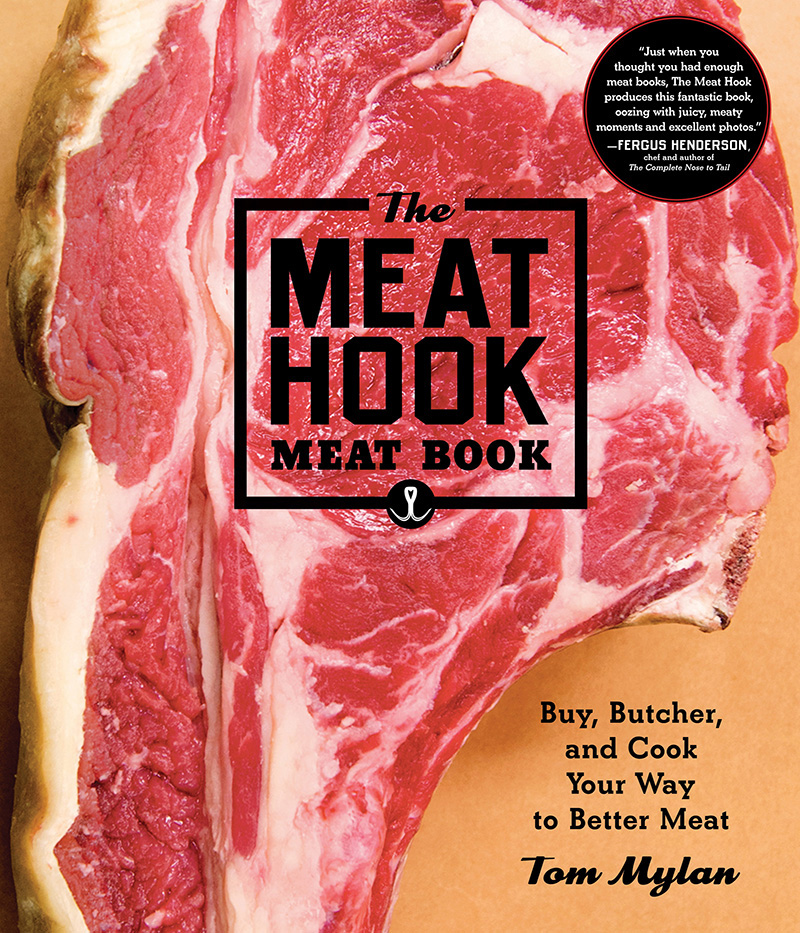

When I met Tom in 2003, he was fond of saying that he had moved to New York City to watch the world burn down. In actuality, he started rebuilding even before the flames went out. When The Meat Hook opened in the fall of 2009, just six weeks after we got married, the expertise and relationships that it took to turn a cavernous bowling-alley-supply shop with filthy carpet and drop ceilings into a living, breathing butcher shop had been years in the making. You cant understand The Meat Hook without understanding the backstory and the gang of weirdos who continue to make Brooklyn the most exciting place in the country to live, work, and eat.

The Meat Hook and The Brooklyn Kitchen, a kitchen-supply shop, cooking school, and food-nerd power center, are two separate businesses housed in the same huge building in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. They opened together on a shoestring budget that was cobbled together with incredible resourcefulness during the depths of the recession posthousing bubble burst. The fact that they didnt just survive but have actually flourished isnt simply a matter of luckits evidence of a fundamental shift in the way we eat, and in what we think businesses can and should do for the communities they serve.

Though Brooklyn is full of young businesses, very few of the people behind them started out with entrepreneurial ambitions. Many of us grew up in the nineties, when selling out was the worst sin you could commit and no one wanted to be The Man. We all wanted to be artists and musicians and writers. So how do you get from the cavalier nihilism of watching the world burn down to owning a business that is based on the earnest concept that supporting local farmers is better for the animals, the farmers, the customers, and the world? If theres one person who promoted the idea that owning a business could be a creative pursuit and a positive force in the world, its cheesemaker Mateo Kehler. In fact, its fair to place a certain amount of blame for the rise of jam operations, pickle concerns, and $9 candy bars squarely on his shouldersthats what an inspiring motherfucker he is.

When I say that he is a cheese wizard, I mean in fact that Mateo actually resembles a wizard. He has these insane eyebrows that sprout out about three inches from his face. Also, his cheese is excellent. In the late 1990s he spent time in South Asia working on economic development projects, and then decided to start Jasper Hill Farm, and eventually The Cellars at Jasper Hill, in Greensboro, Vermont, with his brother, Andy, as a way to use the principles he learned in the Third World to improve the depressed dairy economy there. When he wants to talk to you about economics and liberation and changing the world, it gets real heavy real fast. Tom and I met Mateo not long after we met each other, when we were both working at the cheese counter at Dean & DeLuca. Jasper Hill was just starting to sell cheese in the city, and Mateo called every week to ask us what we thought of their cheeses. As Tom and I moved from job to job and both started writing about food, we stayed in touch with the Kehlers. By that time, Tom was working at Marlow & Sons, a farm-to-table restaurant in Williamsburg that also had a small store where you could get coffee and buy local honey and Toms homemade hot sauce and bitters. It was one of the first spots to truly lose its mind over all things made in Brooklyn, and Tom was the buyer. Journalists from The New York Times and Saveur would call him weekly for the scoop on the new, cool artisan thing. At the same time, he was aging a prosciutto in our apartment. For a year, I would wake up every morning to see the hoof-on hind leg of a pastured hog hanging across our loft apartment in an old sewing factory. Tom always had projects lined up on top of the refrigerator: Green walnut liquor. Hot sauce. Tom started a blog called Grocery Guy and we both wrote for it obsessively, documenting every meal, every project. I had also become an editor and partner at Brooklyn Based, a small media company covering the increasingly insane Brooklyn food scene.

We started organizing a sort of combination artisan showcase, flea market, and party called The UnFancy Food Show once each summer as a way to call attention to all the people we knew in the city and beyond who were growing and making delicious things. At the second UnFancy, in 2008, Mateo spent the entire afternoon proselytizing about his cheese to the customers and about the power of capitalism to the other vendors. Mateos message was this: playing at making something delicious is fine if you want a hobby, but starting a business gives you economic power that can be transformative, and to waste that is, well, fucking stupid.

That was when The Meat Hook became a twinkle in Toms eye. The previous winter, he had become a butcher in the crazy space of just a few months. While organic pickles and local jams and ethically sourced chocolate were all fantastically abundant, it was beginning to seem more and more that what really mattered was meat.

Marlow & Sons and Diner were the first two restaurants in Brooklyn to embrace the idea that buying locally raised animals of known provenance was the most ethical and delicious way of eating meat. The two restaurants, located next door to each other in South Williamsburg, had been the first places to really catch hold in a long-ignored neighborhood. Owners Andrew Tarlow and Mark Firth (Mark has since left the partnership to move to the Berkshires to farm and open his own place) took a real chance opening there, a few doors down from a Hasidic funeral home in the shadow of the Williamsburg Bridge. Andrew and Mark promoted Tom from buyer and manager of their tiny general store at Marlow to butcher in the fall of 2007.

Marlow and Diner had been buying meat from Fleishers Grass-Fed and Organic Meats in Kingston, New York, but Josh and Jessica Applestone, the owners, decided that the economics only worked out for everyone if the restaurants would take whole animals rather than nearly-ready-to-fire cuts. That necessitated having an in-house butcher. Tom became that person, after spending long weeks that fall riding the bus up to Kingston to apprentice at Fleishers.

A year later, in late 2008, Marlow & Daughters, New York Citys first locally sourced butcher shop, opened with Tom at the helm. Inspired by the success of Daughters, and the fact that people really would seek out meat that had been properly raised by local farmers, Tom and the two other butchers at Daughters, Brent Young and Ben Turley, started thinking about opening their own place. Less than a year later, The Meat Hook opened.

In the buildup to the opening of Daughters, Brent and Ben had arrived from Richmond, Virginia, where theyd been working at a butcher shop and in restaurants. Brent had heard through whatever whiskey-saturated grapevine runs between kitchens in Brooklyn and Virginia that Diner and Marlow & Sons were hiring and that they needed someone with experience breaking down whole animals. Pretty soon, Brent was working on the line at Diner and as Toms backstop in the tiny metal boxa walk-in refrigerator, and not a particularly large onethat served as his butcher station. Until Brent came on, Tom had been spending ten hours a day, six days a week, in the box. At minimum.