Thanks to: Barbara Austin, my first reader, for her encouragement, and huge amounts of work on the original manuscript; Anna Rogers, for her clever and charming editing; Sam Elworthy and all the staff at Auckland University Press for their advice and support; Katie Brockie, John Webster, Robin Skinner, Rachel Dodd and Jean and Prue Treadwell for their generosity in sharing cookbooks; all the people who at conferences, at work, at parties and elsewhere have answered my interminable questions about how they cook, eat and shop; and to my family, who have had to eat some unusual meals during this project.

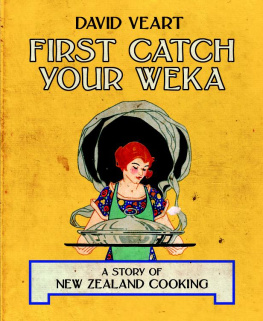

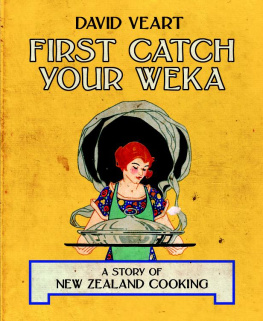

In 1842 Charles Heaphy, explorer, artist and war hero, produced one of Pakeha New Zealands first recipes.

And the weka, uncared for in settlements? Catch it, as Mrs Glass [sic] would say, at Rotoiti or Cape Foulwind; stuff it with sage and onion (for even these condiments accompany the epicurean traveller) roast it on a stick, watch it for half an hour at daybreak, splattering and hissing between you as you make damper or pancake and then serve it upon a saucepan lid no Christmas dinner ever gave more satisfaction.

Using one of cookerys oldest jokes, Heaphy and his weka provide a metaphor for the development of the recipe in New Zealand. Hannah Glasse, the eighteenth-century author of The Art of Cookery, is one of a number of women cookbook writers credited with beginning a recipe, First catch your hare. One explanation for this is that catching may be a corruption of cacheing or casing, which means to take off the fur, but it seems more likely that it was simply a Victorian gentlemans idea of a joke at the cooks expense. Rather more interesting is the culinary conjunction that Heaphys story provides: English cookery meets New Zealand wildlife. Heaphy even anticipated New Zealands later love affair with baking by adding a damper or pancake to the meal. After Heaphy and his weka, recipes would appear in a relentless progression and from our cookbooks we can learn almost as much about New Zealand society as we can about what we have been eating.

I have been accumulating cookbooks since I first became responsible for feeding myself sometime in the early 1970s and left home with the compulsory Edmonds given to me by my mother. It occurred to me some time ago that many old cookbooks were being thrown out so I started to gather them up from op shops, school fairs and from friends and relatives who knew of my increasing obsession. Soon after my cookbook obsession began, I tried mapping out a science fiction novel heavily influenced by Jorge Luis Borges in which the main character, a future PhD student, attempted in his thesis to reconstruct New Zealand history using as his only source a complete set of the Edmonds Cookery Book. The novel vanished without trace; this is my attempt at the thesis a story of New Zealand cooking as it is recorded in our cookbooks and our recipes.

In writing this book I have followed two parallel streams in generally alternating chapters. The main structure progresses chronologically, decade by decade, from Colonial Goose to the Bill Rowling cake, from Mrs Beeton to Julie Biuso, from hangi to the Shacklock range and from Four Square to food festivals. But some aspects of our cookbook history were so overwhelming that a thematic approach was required to tell the story. Why, for example, do we return again and again to the heavy boiled Christmas pudding in midsummer and yet have neglected to invent a satisfactory midwinter festival of our own? Why were New Zealand cookbooks filled with recipes for confectionery? Why were the early European settlers obsessed with baking bread and why do these old bread recipes live on in the Maori world? By examining the recipes we have cooked over the last 150 years, I hoped to get some sense of who we are.

Both recipes and cookbooks contain vast amounts of information about the society that created them. What was fashionable and who was feeding what to whom can tell us about things as diverse as films, fashion and family size. Why do Victorian recipes always seem to contain the spice mace? Why are early bread recipes for such enormous quantities? Why do women on the covers of 1920s cookbooks tend the stove in hats and gloves? What do Hollywood stars have to do with roughage? There are instructions on etiquette which map changes in table behaviour, and in most cookbooks until the 1960s there were home remedies, nursing instruction and meals for feeding the sick. These allow us to investigate a world without antibiotics, inoculation and decent drainage.

Cookbooks note changes in technology. The New Zealand obsession with baking was difficult to indulge before Henry Shacklock introduced the Orion stove. This new improved oven, together with Thomas Edmonds Sure to Rise baking powder ensured that baking could continue to dominate our cookbooks for 100 years. Gas and then electric ranges were introduced and the cookbooks gave the instructions for using these new fuels. Pyrex and aluminium cooking equipment also appeared initially in conjunction with advertisements for the best coal to fuel the Shacklock Orion range and later to take advantage of the new electric stoves. Radio arrived and suddenly the recipe exchange over the back fence was extended nationwide. Aunt Daisy and the other radio recipe recorders made sure that for three decades we all knew what each other was cooking and shared our kitchen favourites. During the 1960s, television transmission began and with it came an assortment of TV cooks, either dapper and English or flamboyant and boozy. We all watched our single channel and the recipes they taught us were spread far and wide.

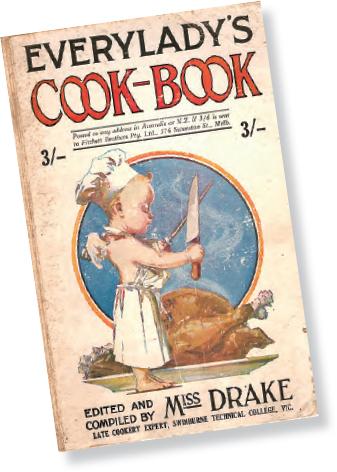

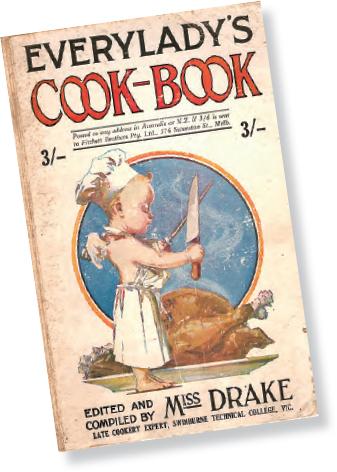

Cooks and cookbooks have travelled back and forth across the Tasman for 200 years. This cookbook, published in Melbourne, was advertised as posted to any address in Australia or N.Z. if 3/6 is sent . LUCY DRAKE, EVERYLADYS COOK-BOOK , FITCHETT BROTHERS PTY LTD, MELBOURNE, 1935, COVER

Cookbooks map the transfer of ideas. At the time New Zealand was settled by Europeans, British food was already a product of empire, in terms of both dishes and ingredients. The English were already eating curries and we in turn wrote recipes for English curry for at least 100 years before we ate anything that originated in India. We have also imported cookbooks throughout our history, another vehicle for the transfer of tastes and fashion, and from the 1900s we watched American films and extended our fascination with this new English-speaking power and the food its inhabitants ate.

One very effective way to exchange ideas is to move large numbers of people about, as happened during the two world wars. The presence of thousands of American servicemen from June 1942 and the arrival of European refugees fleeing from Hitlers terror helped to introduce New Zealanders to instant coffee, Spam and Austrian cakes. The wartime experience of other cultures also emphasised the special characteristics of the New Zealand diet and the increase in new recipes for kai moana and sheep meat after the Second World War grew from this realisation. During the 1960s the cookbooks reflected the increase in overseas travel and the introduction of commercial jet aircraft in the 1970s accelerated this trend.