The fish faces scared me. I was a five-year-old straight out of the supermarket suburbs of Tennessee, where all the seafood remained faceless fillets behind thick sanitized glass. At the bustling outdoor markets of Taipei, not only were the fish laid out in the open, they still had their little features intact. And, I could swear, those glassy eyeballs were looking at me.

Thats probably my earliest food-related memory of Taiwan. I have since come to love the vibrant food markets that line alleys and streets throughout the country. Theyre noisy, messy, cramped, lush, colorful, and everything wonderful all at once. Just like Taiwan.

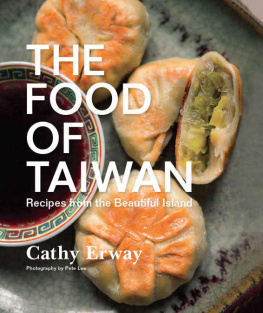

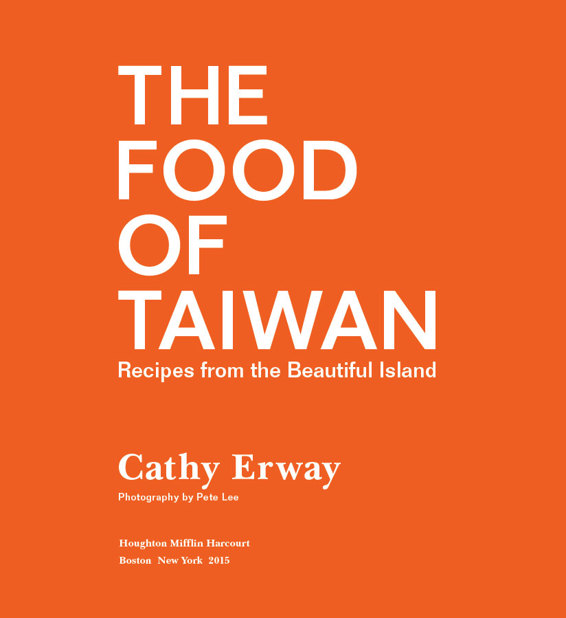

With this book, Cathy brings into sharp focus the wild array of flavors that define Taiwan. She explains how the countrys cuisine has been shaped by its people and the history of the region. Perhaps most importantly, The Food of Taiwan has made all of that available and understandable to those who might be confined to shopping in the aisles of American supermarkets. Taiwanese cuisine has plenty to offerfrom savory oyster omelets to delicate cake-like pineapple tartsand this book helps ensure that all that bounty isnt confined to one small island.

Cathy took on a formidable task by writing this book. After all, Taiwanese people are obsessed with food. I realize thats an assertion that could be made about people from any number of countries, so let me offer up some solid evidence.

In the National Palace Museum outside of downtown Taipei, you can find two of the nations treasures: One is a seven-inch tall piece of jade thats been carved into the shape of bok choy cabbage. The color of the stone perfectly mimics the white and green of real bok choy. Nearby, youll find a brown rock set behind security glass. Why do the Taiwanese love this small, ugly stone? Because it looks like an incredibly lifelike piece of pork fat thats been cooked in soy sauce.

Even describing these artifacts as Taiwanese is complicated, though. The pieces were brought to the country from China by Chiang Kai-Shek in 1947, when his Kuomingtang troops were driven to Taiwan by Mao Zedongs communist party. So while theyre beloved treasures revered by Taiwanese people, theyre not exactly Taiwanese.

The issue of national identity in Taiwan is oftentimes fraught with caveats. When people ask about my East Asian background, the shortest, most accurate answer I can give is, My parents are from Taiwan.

My father is Taiwanese. My mother was born in Taiwan, but her parents were from Fujian. That means Im not exactly Taiwanese or Chinese. These are distinctions that people from Taiwan continue to make to this day. While explaining all of that is cumbersome, the awareness of those caveats means that for many, even those of us who never grew up in the country, history is always close at hand.

Through her familys story and the sections on the politics and history of Taiwan, Cathy thoughtfully and skillfully captures that complex national identity.

In this book, she writes that, as a child, her mother used to chase after a stinky tofu cart like so many American children who have trotted after a tinkling ice cream truck. Many may find it hard to believe that Taiwanese people love this odoriferously offensive food, but its true.

Heres an example from my most recent trip back to Taiwan. While walking down the streets of Taipei with my family, every so often, we would lose my father. Id turn around to see him standing fifty feet back, peering intently down a random alleyway. The guy had literally been stopped in his tracks by the seductive stench of stinky tofu. I kid you not.

In the section on military villages (juan cun), Cathy explains that wheat only became popular after the mainland Chinese moved to Taiwan in the late 1940s. My mother, who was born in 1952 and spent her early childhood in a rural mountain village, even now traces her love for Taiwanese-style soft white bread to the fact that bread was a treat growing up. She only got to have it when she was in the city on special occasions.

When I think about Taiwan, Im flooded with memories of my family that are invariably tied to food. There was always fresh tropical fruit available at my grandparents houselychees, starfruit, papaya, and crisp wax apples (lian wu). On a recent road trip to the hot springs in the north, my cousin stopped at a 7-Eleven for a snack of fish balls marinated in soy sauce, also known as the lu wei that Cathy describes. Steamy, oppressively hot summers in Taiwan meant mountains of shaved ice topped with sweet red beans, grass jelly, and taro root.