Judith MacKenzie

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction: Spinning Rare Fibers

As a civilization, weve been spinning for more than 20,000 years, and during this time weve spun many different fibers. Over thousands and thousands of years, spinners did, and continue to, try everythingwisteria, spiderwebs, kudzu, cedar, raccoon fur, fireweed down, antelope, and many, many other fibers that our curious fingers just cant resist.

Some fibers, such as cotton, flax, wool, and silk, have come forward from antiquity to form the backbone of the modern textile world. Others, such as byssus fiber from sea mussels, nettles, mountain goat, and yucca, could not be domesticated and have faded from use. Some, such as the fibers from woolly mammoths and the tribal wool dogs of the Pacific Coast, vanished from use when the animals themselves became extinct.

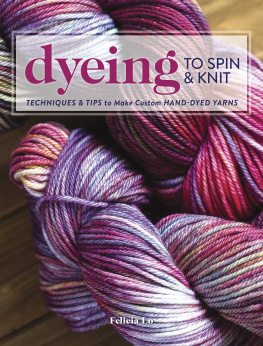

Today, spinners continue to seek out new fibers. In these modern times, science has created two new classes of fibersregenerated cellulosics and synthetics. Made in test tubes and factories, these fibers simply didnt exist until the last century. In the modern textile world, millions of tons of synthetics, reconstructed cellulosics, unending genetically altered cotton, and chemically treated superwash wool flood our throwaway textile world. But Mother Nature has a little backwater or, perhaps more truly, a secret garden of rare and precious fibers. These rare fibers cant be produced in amounts large enough to meet the demands of mainstream production and mass markets, but theyre perfect for artisan fiber processers and handspinners.

In this book, well look at some of these fibers, which I consider gems of the handspinners world. Well learn about the animals that produce these fibers, the cultures that sustain them, and how they can be used to create fabric, whether knitted or woven.

When I first started thinking about a book on rare fibers, I was working away on one of my ongoing textile adventures. I wanted to look at all those mysterious fibers that have been spun throughout historyspiderwebs, hummingbird down, and, for heavens sake, the tiny gold strands of sea mussels that were spun into thread and woven into King Henry VIIIs famous golden shirt.

The question I kept asking myself was not how on earth did spinners manage to spin spider silk to make gossamer or how did they manage to gather the byssus fiber from the sea mussels to make gold thread, curious and interesting as that information might be. Rather, I wanted to know what on earth possessed them to consider trying it in the first place.

Its not that we had a shortage of fibers to spin, even back in the sixteenth century. We were not driven to dig through the sand on our hands and knees to collect tiny fibers less than a third of a human hair in diameter because we were naked and freezing. We had, at the time of Henrys beautiful shirt, ready access to many kinds of wool as well as exquisite flax. We also had silks and cottons of astonishing quality that had begun to make their way to Europe from the Easta positive outcome of the Crusades. What, then, drove us to even consider spinning the anchoring fibers of a rare sea mussel? It definitely wasnt need. Instead, I think it was desirea deep and driving hunger for the rare, the unusual... and the exquisitely beautiful.

For me, this urge is whats often most intriguing about textilesnot just how they were produced, gathered, and spun, but why. What made a medieval spinner look at sea mussel fiber and envision the possibility of extraordinary fabricone that we would wonder and think about nearly 500 years after it was spun and woven?

As I thought about it, I realized it wasnt a question of having to try and enter a medieval spinners mind for insight; I could look a little closer to home. All I had to do was remember walking under a brilliant blue Montana spring sky and seeing it reflected in the water of beaver dams along a creek where trumpeter swans rested on their way home to the far north. There, I found lovely down feathers caught in the wild prairie grasses and tangled in the chokecherries and wild thornapple. I carefully gathered them up, put them in my pocket, and took them home to spin.

When I slip on my little silk-and-swansdown handwarmers (see image in ) for a walk on the wild West Coast where I now live, I recall that other time and place, as if I were there again.

And I remember naturalist John Muirs words: Everyone needs beauty as well as bread.

Judith

CHAPTER ONE

A Rare and Luxurious Excess

Modern spinners live in the best of all possible times. The world of fiber is at our fingertipsstunning wild silks from India, cashmere from the rugged northern mountains of China, camel down from Mongolia, exquisite alpaca and rare vicua from the Andes, yak from Nepal and Tibet, and qiviut from the frozen wilds of the Canadian North. All of these are available for us to spin in a number of enchanting ways.

In addition to this amazing variety of luxurious fibers, we have the rarest luxury of all, the luxury of time. We no longer have to spin our own bedsheets. We now have time to study and practice. We have time to learn about unusual fibers, their properties, and how best to use them. We have time to create objects that will bring pleasure in their use for many years to come, whether its a pair of everyday socks or an exquisite shawl.