Great care has been taken to ensure that the places, people, groups, and events in this story are historically accurate. In cases where facts cannot be verified, the author has relied upon the memory of those interviewed.

The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

Some of the names in this book may have been changed to protect the privacy of certain individuals.

Copyright 2009 by Vic Shayne

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Small, Martin, 1916-2008.

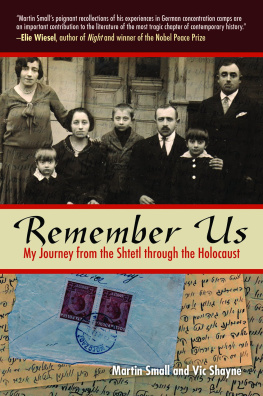

Remember us : my journey from the shtetl through the Holocaust / Martin Small & Vic Shayne.

p. cm.

9781602397231

1. Small, Martin, 1916-2008. 2. Jews--Belarus--Mouchadz--Biography.

3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)--Belarus--Personal narratives.

4. Mauthausen (Concentration camp) 5. Mouchadz (Belarus)--Biography.

6. Baranowicze (Poland)--Biography. I. Shayne,Vic, 1956 II. Title.

DS135.B383S677 2009

940.53 18092--dc22

[B]

2009024775

Printed in the United States of America

To my mother and father,

Esther and Shlomo, and my two little sisters, Elka and Peshia.

May you always be remembered.

Authors Note

When I began writing this book in Martin Smalls name, he was a sprightly eighty-seven-year-old. He was lucid, quick-witted, and light on his feet. He enjoyed a good joke, an occasional shot of his favorite Russian vodka, challenging his rabbi in the middle of Shabbos services, and creating works of art in his basement. He had a wonderful intellectual curiosity, a gift for languages, and a love of music. However, both he and I were somewhat concerned that this bookMartins life storywould not see the light of day until after his passing. For this reason, I worked around the clock and, for nearly four years, spoke with Martin at least once a day. I was in awe of his memory, especially as I checked, to the best of my ability, his recollections against historical facts and events. By the age of ninety-one, after more than eight decades had passed, Martin was still remembering the names of the children in his neighborhood, conversations with his grandfather, and the layout of his shtetl. The summer before Martins ninety-second birthday, the first printing of this book came out. He was thrilled not merely to see his story in print, but to be able to physically hold it in his hands. He realized a life-long dream of memorializing, in permanent form, the family that was taken from him so that he could connect them to the new family that he and his wife, Doris, created here in America. He passed on an invaluable legacy. Shortly after Martin and I celebrated the release of this book, he was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer and passed away in Doriss loving arms in his home on a cold November morning just weeks before his ninety-second birthday. Days before, I visited him on his death bed and he reiterated the solemn words that he had spoken throughout his sojourn during the Holocaust: Jerusalem, if I forget thee, may I lose my right arm. In doing so, he cast his eyes upward and they filled with tears. His love for his people, his religion, and his family were inseparable and forever in his heart. It is my hope that this love shall grant you cause for reflection as you read his story and consider what has forever been lost.

Vic Shayne

Preface

I was twenty-five years old in the beginning of spring, 1942. I stood at the wooden counter in my mothers kitchen looking for something to eat. There was a slight chill in the air. I rubbed my arms with my hands. There was no fire burning anywhere in the house. My entire family was in the living room, along with some guests, huddled together waiting. Once in a while, my father would stand up and look out the window then go back to the sofa beside my mother. It was the middle of the day. Nobody was working. My stomach growled. I was growing hungrier by the moment. What was I looking for in the cupboard? Anything. There was nothing left. I stood staring at an empty plate, my thoughts drifting far away. It was too quiet. I looked out the window. The street was deserted. I turned around and sat down on a chair and crossed my legs. This kitchen that I helped my father build was, for once, quiet. It wasnt natural. My little sisters and my mother werent baking or cooking. It was a foreign feeling. No pots and pans and baking dishes were clanging. The laughter was gone. The stoves were cold to the touch. It was deathly quiet. Then I heard a boom coming from the living room. What was that? It sounded like a log smashing into the front door. It jolted me. Everyone in the living room had jumped from the shock.

Boom, boom, boom! Fists were pounding on the door and a young, familiar voice was shouting. Demanding. Open this door! Open or Ill smash it in. I ran to the door. Everyone was wide-eyed. My father stood with his fists clenched at his sides as I opened our front door. In front of me stood my boyhood friend, Stach Lango. His seething expression, his twisted mouth, and sick gaze belonged to somebody else. What happened to him? He pointed a pistol to my face, grabbed me by the collar, and said, If you fight me, Ill shoot your mother, your father, and your two sisters right in front of you. What was I to do? It was hopeless. Stach pulled me by the shoulder and yanked me out of my house. My family watched helplessly as I was dragged into the empty street and pushed all the way to the police station and into a room with a wooden table in the center and a glowing fireplace by the wall.

A small stack of wood and some iron pokers leaned against the dirty, paint-peeling wall. Once inside, still with a pistol pointed at my head, I was forced to undress. Hurry up, goddammit, Jew! Then Stach tied me to a table in the middle of the room. I couldnt move. My wrists were tearing from the ropes. My eyes followed him as he tucked his gun inside his waistband. He picked up one of the iron pokers and angrily shoved the end of it into the embers. He knew I was watching and relished his power over me.The iron grew hotter and hotter until the tip of it pulsated in red and white. Im going to kill you, Jew, he said. His voice was monstrous. He brought the iron toward me and I could hardly bear the heat even from several inches away. Smoke was rising from the glowing tip.

Im going to kill you slowly. I want to hear you scream. My heart raced and I felt sick. The poker was pushed slowly and torturously toward my face, and all I could think was, God, take me quickly. I called out for GodGod my rescuer and confidant; the God I knew as a Yeshiva student; the God of our Torah. Where was God in all of this? I braced myself for the worst as Stach came toward my eyes with the iron. Then the door flew open and Stach turned to face his friend, who was exhaling puffs of steam and trying to catch his breath. He whispered something in Stach Langos ear. I couldnt hear what was being said, but without a word spoken to me, I was untied and set free. I dont know why. I dont know to this day why they let me go. I ran out the door and ran and ran until I came back to my house in a pool of sweat and called for my mother as I burst through the front door. I saw her face through my tears, and she opened her arms. I held her tightly and felt every fiber of her dress in my hands. I breathed in her hair and laid my head in my own perspiration and in the tears running down her neck, soaking her collar. I couldnt let go, and she held me; I was her baby and she held me. She sat down and held my head on her lap and stroked my face. I sobbed and she tried to console me.