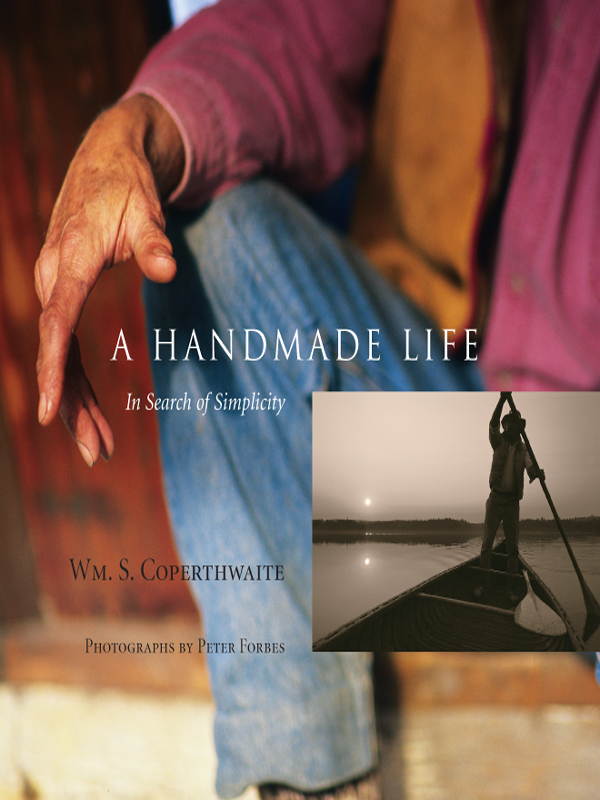

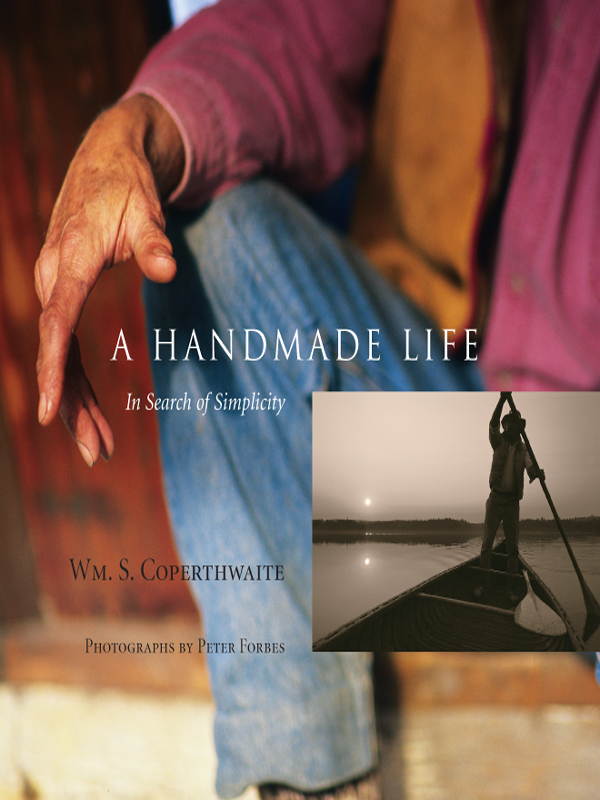

A HANDMADE LIFE

IN SEARCH OF SIMPLICITY  WM. COPERTHWAITE

WM. COPERTHWAITE

Photographs by Peter Forbes

CHELSEA GREEN PUBLISHING COMPANY  WHITE RIVER JUNCTION, VERMONT

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION, VERMONT

CONTENTS

IT WAS JUST PAST MIDNIGHT when I slipped my canoe into the water at Duck Cove and headed due east, exactly as the instructions said, to the point of shore where he would meet me. A green light clung to each of my paddle strokes. The bay was stunningly calm, and so silent that I could hear a pair of raccoons breaking open mussels on the distant shore. Our two canoes met and neither of us spoke a word, sensing that it was better to let the night speak for us. The moonlight cast long shadows on the spruce-lined shores and the channel narrowed, bringing us eventually to the powerful tiderip through which we passed to enter Bills home. That evening, the tide was going our way and I rode the current, pulled deeper into a place that would change my life.

The rushing tide empties into a calm and large expanse of shallow water called Mill Pond, the heartbeat of Bills homestead. Pulled by Earths relationship to the moon, the pond fills and empties again twice a day, living a dramatic life of tides: waves of green water, mudflats, mussel beds, eagle, osprey, and heron. Ive been coming here for ten years now and its this ever-changing pond, the ebb and flow of seawater, that tells me Ive arrived.

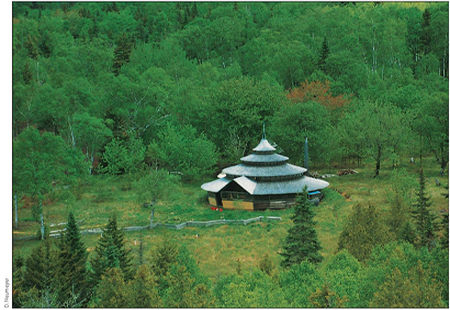

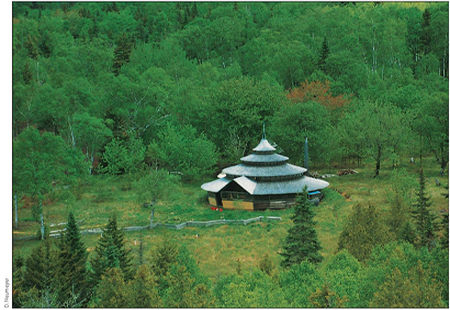

Bill and these four miles of coastline have gently shaped one another in a relationship that has lasted forty years, in which an enduring quality of care and attention has made him and the wilds inseparable. They live together. Hes built osprey nests, gathered his water from hand-dug springs, and harvested mussels. Hes made footpaths through the woods, where after years of pulling fir saplings by hand, he now walks through glades of birch and maple. Hes transplanted the smallest of flowers and the heaviest of stones to make his place complete. He hammered rock to create a landing for his canoes, and hes built a beautiful home by hand from wood and sun.

Bill and I have crossed miles of open water to explore a stretch of beach that might yield rope, or whalebone, or a revealing conversation about abundance and fairness. Bills life has quietly offered me the proof that an individual, in our country and in this age, can still create a unique and authentic life, and that the art of that life is in its wholeness with its place. In watching how Bill carries the land in his heart and mind, I have learned that the essential purpose of saving land is to create the chance that each of us, in our own way, might live in a healthy relationship with the rest of earthly life andin so doingto elevate what it means to be human. We need Bills story to remind us of other ways of living.

I dedicate these images to my colleagues at Maine Coast Heritage Trust and the Trust for Public Land who are endeavoring to keep all life healthy at Dickinsons Reach, and to everyone who seeks a relationship with land in their own journey to lead a unique life.

PETER FORBES

Fayston, Vermont

The main thrust of my work is not simple livingnotyurt design, not social change, although each of these isimportant and receives large blocks of my time. Butthey are not central. My central concern is encouragementencouraging people to seek, to experiment, toplan, to create, and to dream. If enough people do thiswe willfind a better way.

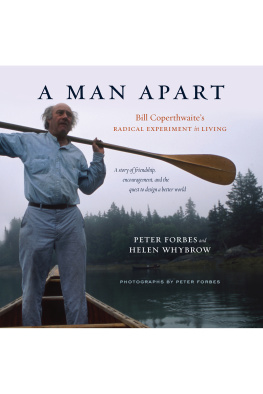

T hese are the words of Bill Coperthwaite. This book is about his lifelong commitment to living in a way that can create a world of justice, beauty, and hope.

Bill Coperthwaite has spent better than forty years on a homestead in the wilds of Maine. He has also traveled the globe in search of cultural skills, practices, and designs that can be blended and enhanced for contemporary use. He builds as much for joy in the process of building as for the beauty of the result. He is as devoted to working with his hands as he is to the highest ideals of democracy. He lives on the furthest margins of the market economy as an experiment in sustainable living.

Several themes anchor his life practices: education, nonviolence, simple living, democracy, and the fallacy of discipleship. Bill has developed his thinking in detail around each of these, yet they are interrelated and mutually reinforcing, and my attempt to give each area separate attention for the sake of clarity must oversimplify.

Bills thoughts and actions have been profoundly shaped by those he describes as people in particular whom I admired for their intellectual acuity, their work with their hands, and their dedication to a better societymen such as Morris Mitchell, Richard Gregg, and Scott Nearing. Each of them influenced Bill in specific ways as he set his own course. He has neither followed nor looked to be followed, yet his way of being in the world embraces the linking of past, present, and future, providing a sense of irrefutable hope and abundant optimism.

EDUCATION

Bills undergraduate years at Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine, proved uninspiring. Real learning took place elsewhere, out of the classroom and away from campus. He read Gandhi on his own. He established connections with the International Student Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, jumping a bus to spend weekends discovering a wider world than the one offered through higher education. A senior semester abroad at the University of Innsbruck stimulated a yearning for culture and perspective; he became an expatriate who reluctantly returned to Bowdoin to complete a degree in art history.

Through connections in Cambridge, he was invited to apply for graduate study by Morris Mitchell, the director of the Putney Graduate School of Teacher Education. Mitchell, renowned for his slow moving, bold thinking presence, had come to Putney with a reputation as a tenacious southern Quaker and visionary organizer of school-based rural cooperatives in Alabama and Georgia. His Quaker faith and experiences as a soldier in World War I had made him a resolute pacifist. As an educator, he embraced experiential education and the application of knowledge for social purposes. In Mitchell, Bill found a mentor who blended cabinet-making and gardening with his leadership of the school. The students at Putney Graduate School were apprentices to a special view of education and the role of the teacher. The life of a teacher, Mitchell instructed, is as important a life as any person may live. Viewed broadly, it is a life of leadership in a world of contradictions and crisis. It is a particularly human life, one of total involvement with human beings as they face human questions.

WM. COPERTHWAITE

WM. COPERTHWAITE