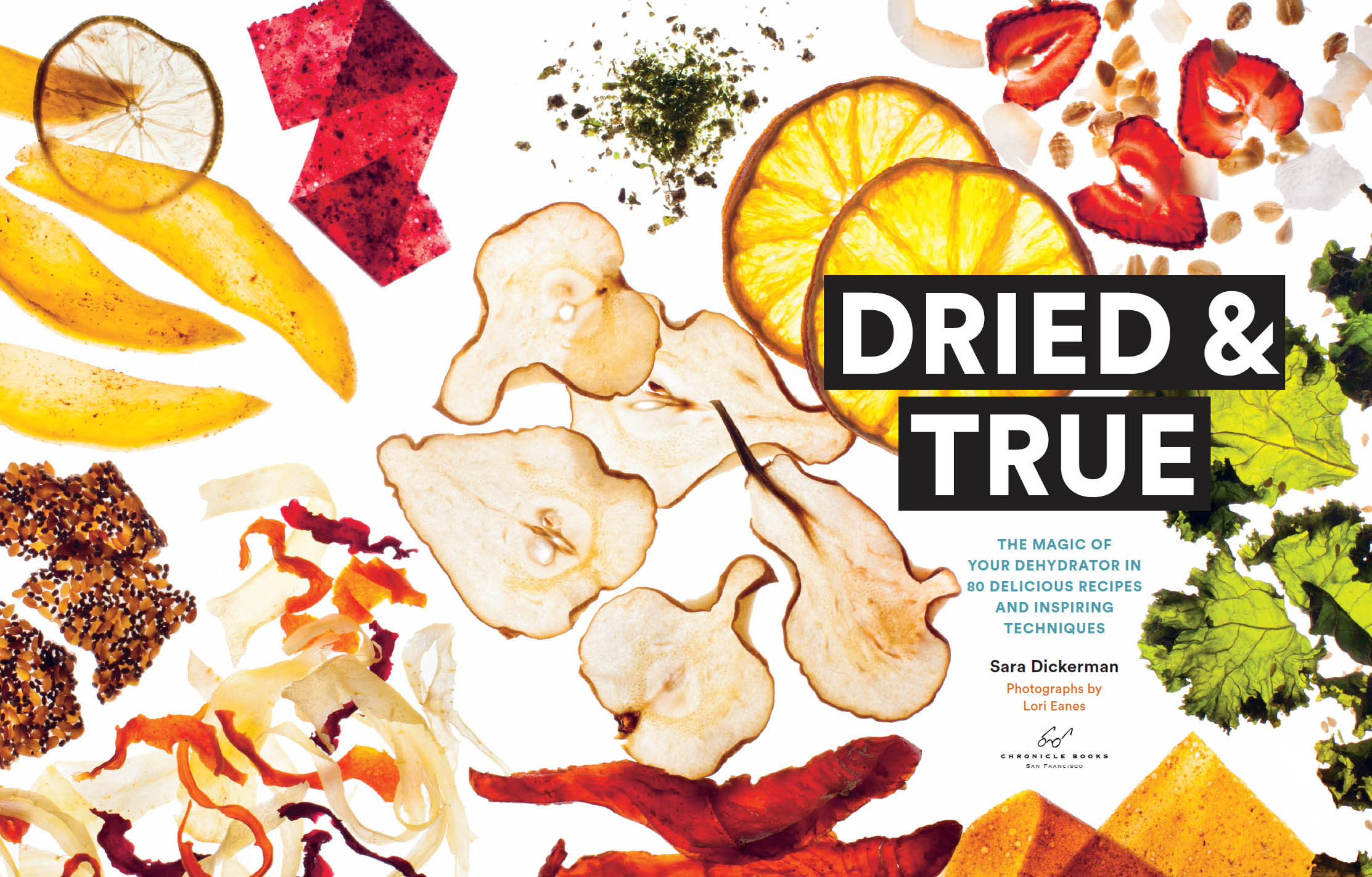

Text copyright 2016 by Sara Dickerman.

Photographs copyright 2016 by Chronicle Books LLC.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 9781452148700 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Names: Dickerman, Sara 1971- author.

Title: Dried & true : 80 big-flavored dehydrator projects for fruits,

vegetables, powders, jerky, and more / Sara Dickerman.

Other titles: Dried and true

Description: San Francisco : Chronicle Books, [2016] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015039650 | ISBN 9781452138497 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking (Dried foods) | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX826.5 .D53 2016 | DDC 641.6/14--dc23 LC record

available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015039650

Designed by Alice Chau

Photographs by Lori Eanes

Food styling by Randy Mon

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

INTRODUCTION

This book is a guide to using a home dehydrator creatively. I had long been a fan of dried fruit and beef jerky, but I purchased them from grocery and specialty stores. Eventually I began to see ambitious chefs incorporating dried elements into their work, from flavorful powders to little nuggets of chewy fruits and vegetables. I got curious and proposed an article on the subject to my editor at Slate, and acquired my first food dehydrator. I played around with drying strawberries, cherries, and even watermelon. I continued to experiment with drying herbs, meats, fish, vegetables, fruits, and even flowers, and I shared ideas with friends for how to best use their dehydrators.

I found that most sources of information on dehydration were less playful than I like to be in the kitchen. I wanted a book full of bold flavors, timely ingredients, and fun ideas for presentation. And so I wrote this book. In these pages, I cover the basics: Preparation, drying, and storage of almost any food you might think of drying. The recipes also invite you to do more, to harness the dehydrator not just as a practical tool but as a means to delightful results. With its help, you can make such items as pesto powder and citrus sugar, elegant vanilla pear slices and kid-pleasing fruit leathers, rustic chipotle jerky and hearty dried mushroom soup for backpacking. Im confident youll discoveras I havethat the food dehydrator can be a winning and versatile kitchen addition.

DRYING FOOD

Is it sunny as you read this? Is there a gentle breeze stirring? If so, you have what it takes to dry food, because Earths atmosphere is the oldest, largest dehydrator there is. Drying food as a means of preservation is older than history, no doubt older than agriculture itself. Somewhere along the way, a Stone Age hunter happened to chew on a leathery strip of old meat, and beef jerky was born. And the first raisins were probably a cluster of shriveled wild grapes that some gatherer picked and stored for future use.

Simple as it was, the calculated drying of food items was a huge development; it was a bet on the future and a premeditated act of planning. Drying made it possible to extend a healthful diet beyond the immediate stages of a fresh kill or a windfall of fresh edible plants. When food is purged of most of its moisture, it no longer provides a good habitat for the rascally strains of bacteria, yeasts, and molds that can ruin it. (Some microbes, however, do help preserve food through the process of fermentation.) Dried food is also lighter and thus more portable than moist food, helping to ensure nutrition even as people traveled and explored new territories.

Drying is still a major means of preserving food. Rice, seafood, pasta, grains, legumes, meats, fruits, spices, and vegetables are all still commonly dried for storage in countries around the world. The majority of the worlds population still survives without a home refrigerator, so without dried food, there would be a constant struggle against spoilage.

Throughout history, drying processes became more complex and efficient. People discovered that fruits and vegetables dried more quickly if elevated off the ground by even a rustic mesh of branches. They learned that dairy could be dried too. In the thirteenth century, Marco Polo observed Tartar armies drying milk in the sun, so they could carry the resulting powder with them on their journeys. People also found that fish and meat dried better and more safely with the addition of salt. And smoke was often used as a part of the drying and preservation process of fish and game.

Today there are several mechanical means of drying food. Industrial techniques like freeze-drying work to very efficiently preserve food. Freeze-drying systems first freeze food, and then warm it gently, under very low air pressure. In this environment, the ice in these foods turns into a gas, skipping the liquid stage. The process leaves behind a crunchy, structurally sound version of the dried foodlike uncannily crisp peas and raspberrieswhich can be simply rehydrated by soaking in water. Unfortunately, such freeze-drying systems arent designed or priced with the home cook in mind; they cost thousands of dollars.

Old processes such as heat (like the sun) and air circulation (like the wind) are still used as well. Commercial facilities have large dryers that pass warm air over apricots and apples or strips of meat en route to jerky. The most straightforward versions of these dryers simply vent damp air away from the drying chamber like a clothes dryer does; others cool and recirculate the air with a heat pump.

Our home food dehydrators are simply more compact versions of the hot-air and venting method. They come in a few shapes and sizes, but all rely on the circulation of warm air to draw moisture away from ingredients to dry them. Because the technology is relatively simple and inexpensive, we are lucky; we can use dehydrators for an expansive variety of at-home food projects. This book will focus on just that, from basics like dried apricots to more involved projects like lamb jerky.

It is ironic, perhaps, that I would be writing a book about dehydration. Rainy Seattle, where I live, isnt a place where you typically think of things drying out. If you take a look at the U.S. governments Mean Annual Relative Humidity map, my home in Seattle sits in the middle of a green splotch, indicating annual humidity average of about 73 percent, about twice that of Phoenix. But I consider my hometowns lack of aridity a good testit means that if I can make amazingly tasty snacks, meals, and edible gifts with my home dehydrator, then you can too. If you happen to live in Phoenix, youll just be able do it more swiftly.

I came to dehydration as a skeptic. Why would I want to dry my own foods when grocery stores all around me sell beef jerky, fruit leathers, and dried fruit galore? There is no driving need for me to dry my own food. Im not a raw foodist, so Im not concerned about the temperature at which my food is prepared. I dont have, say, an apple orchard that would require my saving vast quantities of produce. I dont backpack often enough to require dried meals in great quantities.

In my case, the line between need and pleasure is consistently blurred. And when used with a spirit of curiosity and fun, the food dehydrator delivers big on delight. Working at home, with the best foods I can grow or purchase, I am able to get an incredibly wide range of fresh, intense flavors with my dehydrator. Fresh herbs are transformed into vivid seasoning powders, grass-raised beef and lean buffalo make for the most flavorful jerky Ive ever tasted, and crunchy little seeds can be made into satisfying crackers and granolas (many of which are gluten-free, too!).

Next page

![Tammy - The ultimate dehydrator cookbook : [the complete guide to drying food, plus 398 recipes, including making jerky, fruit leather, and just-add-water meals]](/uploads/posts/book/102970/thumbs/tammy-the-ultimate-dehydrator-cookbook-the.jpg)

![Ferguson September - The ultimate dehydrator cookbook: [the complete guide to drying food, plus 398 recipes, including making jerkey, fruit leathers, and just-add-water meals]](/uploads/posts/book/85869/thumbs/ferguson-september-the-ultimate-dehydrator.jpg)