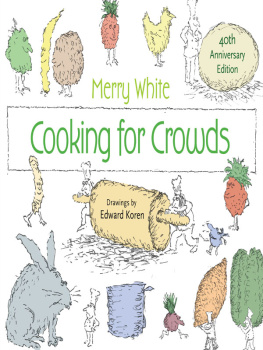

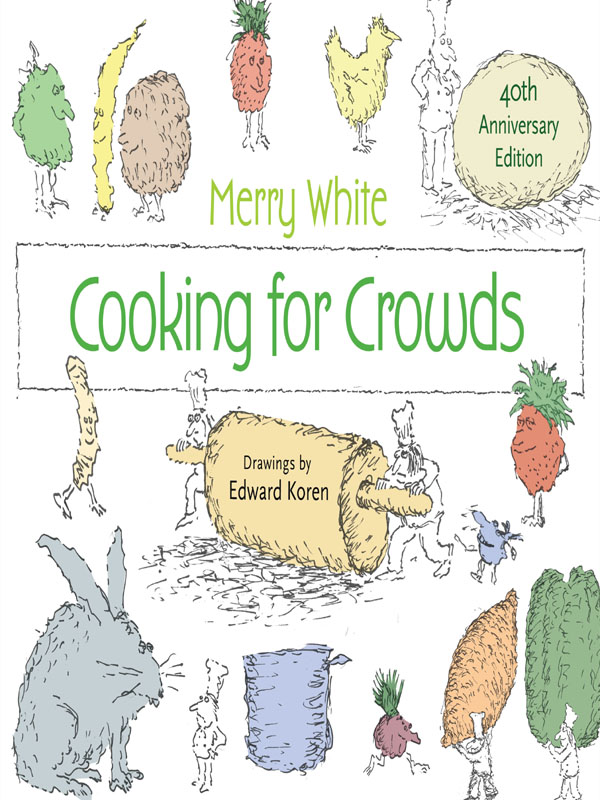

Cooking for Crowds

Merry White

Drawings by

Edward Koren

With a new foreword

by Darra Goldstein

and a new introduction

by the author

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustrations Edward Koren. Jacket design by Leslie Flis.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

White, Merry I., 1941

Cooking for crowds : 40th anniversary edition / Merry E. White ; drawings by Edward Koren ; with a new foreword by Darra Goldstein and a new introduction by the author. 40th anniversary edition.

pages cm

Includes index.

Summary: When Cooking for Crowds was first published in 1974, home cooks in America were just waking up to the great foods the rest of the world was eating, from pesto and curries to Ukrainian pork and baklava. Now Merry Whites indispensable classic is back in print for a new generation of readers to savor, and her international recipes are as crowd-pleasing as everwhether you are hosting a large party numbering in the dozens, or a more intimate gathering of family and friends. In this delightful cookbook, White shares all the ingenious tricks she learned as a young Harvard graduate student earning her way through school as a caterer to European scholars, heads of state, and cosmopolitans like Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. With the help of her friend Julia Child, the cook just down the block in Cambridge, White surmounted unforeseen obstacles and epic-sized crises in the kitchen, along the way developing the surefire strategies described here. All of these recipes can be prepared in your kitchen using ordinary pots, pans, and utensils. For each tantalizing recipe, White gives portions for serving groups of six, twelve, twenty, and fifty. Featuring a lively new introduction by White and Edward Korens charming illustrations, Cooking for Crowds offers simple, step-by-step instructions for easy cooking and entertaining on a grand scalefrom hors doeuvres to dessertsProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-691-16036-8 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Quantity cooking. 2. International cooking. I. Title.

TX820.W48 2014

641.57dc23

2013024597

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon, Scala Sans and Hardwood LP Std Display Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Meghan

Contents

Foreword

When Cooking for Crowds first appeared in 1974, its recipes seemed radical for the times. The books author, Merry (Corky) White, was innovative, bold in her palate, and anything but prescriptive in style. As a young caterer, she aimed to turn catering into an art, to go beyond the standard presentation of ho-hum dishes like chicken tetrazzini. She wanted to dazzle her guests, and she insisted that the American palate is far more adventurous than most people make it out to be. Cooking for Crowds propelled readers on an eclectic gastronomic tour of the world, all the while reassuring them that there is no need to be anxious when cooking for a crowd, whether six people or fifty. And no need to be anxious about using unfamiliar ingredients! Corky convinced her readers that they could bake a great cake and enjoy it, too.

To situate Corkys inspiring book, we must travel back in culinary time and recall the American palate of 1974, before any food revolutions had swept the country. French cuisine still held sway in upscale restaurants across the United States, where affuent diners could demonstrate their distinction by ordering foie gras and escargotsthis was la grande cuisine classique, not the nouvelle cuisine just coming into vogue. Nationwide, the landscape was defined largely by French and continental restaurants, or fast-food and family joints. It is hard to imagine that dishes we now take for grantedGreek moussaka, Swiss fondue, Italian pasta primaverawere then considered exotic.

Only after the reforms of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act did hole-in-the-wall ethnic restaurants begin to appear with any frequency. These unprepossessing places promised adventurous eaters an expanded palate, an antidote to the predictable fare of most other restaurants. The general discomfort with foreign foods further eroded when Richard Nixon visited China in 1972. Television networks offered live broadcasts of the banquet Prime Minister Chou En-lai held in Nixons honor, triggering a national desire to eat authentic Chinese food, beyond the chop suey and chow mein of Chinese-American restaurants. Even so, Nixons visible befuddlement at the chopsticks in his hand underlined to viewers how foreign Chinese culinary culture really was.

It took the culinary revolution of the 1970s to definitively change peoples attitudes about foods, both foreign and local. In 1980, the New Yorkers Calvin Trillin declared Henry Chungs San Francisco Hunan Restaurant the best restaurant in the world, while Gilroy, California, held its second annual festival in celebration of the garlic for which it is famed. Hank Rubins Pot Luck restaurant in Berkeley had fomented revolution in the 1960s, followed in 1971 by Alice Waterss Chez Panisse, whose many talented cooks went on to spread the gospel of good food throughout the country. The epicenter of esculent activity was Northern Californiathree thousand miles from the East Coast, where Corky White livedbut the shock waves quickly spread.

Those were heady times, and the social and political activism of the sixties was reflected in the ways people ate. The natural foods movement had brought an awareness of fresh food to the table. Palo Altos newly opened Good Earth restaurant transformed lackluster brown rice into tasty fare, as did the Moosewood Collective in Ithaca, New York. Celestial Seasonings came out with herbal teas that seemed astonishing (Americans apparently had never heard of tisanes). Anna Thomass Vegetarian Epicure lent vegetarianism cachet. But national culinary awareness still lagged, as evidenced by President Gerald Fords gaffe at the Alamo, when he publicly bit into a tamale still wrapped in its cornhusk. Our cultural cluelessness was at least somewhat mitigated by several excellent cookbooks that appeared in the early 1970s, all considered classics today: Paula Wolferts Couscousand Other Good Food from Morocco, Marcella Hazans The Classic Italian Cookbook, and Madhur Jaffreys An Invitation to Indian Cooking.

Corporate America did little to encourage the nations culinary sophistication. Test-kitchen developers focused on convenience instead. More women than ever were joining the workforce, and many were finding it difficult to get a good dinner on the table after a long day at work. The big food companies stepped in to help them, creating new products like Hamburger Helper (introduced in 1970) and Stove Top Stuffing (brought to market in 1972). Meanwhile, Mrs. Fields and Mr. Coffee wooed the American public with name brands of cookies and coffeemakers. Many women felt torn between ease and sophistication.

Next page