INTRODUCTION

Hellboy and the Adventure of Reading

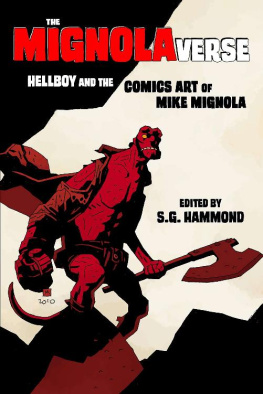

Figure 1. Mike Mignola, Hellboy: The Fury, no. 2, cover. Dave Stewart, color. Dark Horse Comics, 2010.

You are given a book from the school library. In the lower classes, books are simply handed out. Only now and again do you dare express a desire. Often, in envy, you see coveted books pass into other hands. At last, your wish was granted. For a week you were wholly given up to the soft drift of the text, which surrounded you as secretly, densely, and unceasingly as snow. You entered it with limitless trust. The peacefulness of the book that enticed you further and further! Its contents did not much matter. For you were reading at the time when you still made up stories in bed. The child seeks his way along the half-hidden paths. Reading, he covers his ears; the book is on a table that is far too high, and one hand is always on the page. To him, the heros adventures can still be read in the swirling letters like figures and messages in drifting snowflakes. His breath is part of the air of the events narrated, and all the participants breathe it. He mingles with the characters far more closely than grownups do. He is unspeakably touched by the deeds, the words that are exchanged; and, when he gets up, he is covered over and over by the snow of his reading.

Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street

I think that the young Walter Benjamin, the one who wrote so winningly of book collecting and the wonders of childrens books, might well have appreciated what the medium of comics had to offer. And I would go so far as to speculate that there are aspects of Mike Mignolas Hellboy comics that might have resonated particularly well with his bookish sensibility.

For Benjamin, the library was a living thing, and any really worthy book collection would include what he called booklike creations from fringe areas. It hardly requires a stretch to drag comics into this, whether in the ephemeral forms of a periodical comic book or a clipped newspaper strip, or the voluptuous, archival reprint editions that present full-sized facsimiles of a masters original artwork on high-quality paper (the sumptuous, oversized reprints of Hellboy material are even called Library Editions).

Benjamin evokes a child swept up in the swirls of words within the coveted book, but he has also written of the particular ways in which illustrated books activate their young readers: This resplendent, self-sufficient world of colors is the exclusive preserve of childrens books. There is something a little subversive about these pictures, insofar as they are more seductive or distracting than instructional.

The kind of reading that Benjamin describes is fundamentally dialogic. Ive elsewhere quoted Lynda Barry on the subject of playI believe a kid who is playing is not alone. There is something brought alive during play, and this something, when played with, seems to play backand have extended her notion of play to the act of reading. Reader and book are entwined; neither exists without the other. The unread book does not tell its stories. This is surely true of comics and their readers as well; as so many comics theorists have noted, the medium makes unique demands of its readers and thereby engages them all the more.

Benjamins achingly beautiful evocation of a child reading a coveted book speaks to me as a reader, but it speaks to me more loudly as a reader of comics. Jules Feiffer, who apprenticed with Will Eisner on The Spirit before becoming a formidable creator of both comics and childrens books, has written of the riotously colorful fantasias of the superhero comics that he cherished as a child: in a world of endlessly imposed expectations, comic books offered a relief zonewithin this shifting hodgepodge of external pressures, a child, simply to save his sanity, must go underground. Have a place to hide where he cannot be got at by grownups. With [comic books] we were able to roam free, disguised in costume, committing the greatest of featsand the worst of sins.... For a little while, at least, we were the bosses. The antisocial influence that cultures moral arbiters ascribed to these seductive and distracting comics were, for Feiffer and As a child, I was never allowed to buy as many comics as I desired. Friends and I swapped some (and furtively bought, swiped, and hid others), and thensomewhat less so nowthe wait between installments could seem excruciatingly long (a month was longer for me back then; now I barely note their thuddingly regular passage). Finally, new issues would appear on whatever Wednesday it was, and I would rush home to become wholly given up to the soft drift of my comics. The comics themselves certainly didnt constitute a soft drift, filled as they were with battles, cosmic odysseys, neurotic self-questioning, masks, capes, superpowers, secret identities, and secret weaknesses. But reading them was just as peaceful and exciting a project as Benjamin makes reading out to be, and I surely mingled with the characters to a degree that slightly alarmed my parents.

But reading habits change, as Benjamin notes, and my cathection onto these fictional heroes ebbed, replacedup to a pointwith a new fascination for the artists and writers who crafted these comic books. The fictional worlds lost some of their hold over me, and I no longer arose covered over and over by the snow of my reading.

Then I found Hellboy (figure 1). To be sure, Id known of him for some time. I had the first collected story arcs, Seed of Destruction (1994) and Wake the Devil (1996), and Id liked them well enough (figure 2). But I could never work out the publication schedule or the reading order, and every time I thumbed through a collection at the comics store, I couldnt shake the feeling that Id read it before. It always seemed to involve Nazi gorillas. Gorgeous art, but not a story that I needed to have told. I was also peripherally aware that Mignola was no longer drawing the character and only cowriting most of the stories. Pure corporate product, I figured, a cash cow for Dark Horse Comics without artistic integrity.