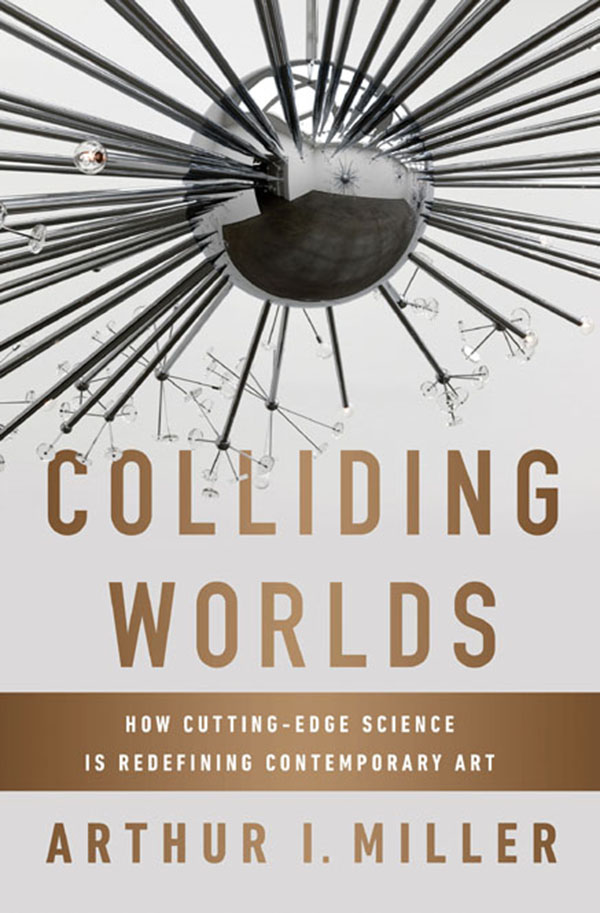

HOW CUTTING-EDGE

SCIENCE IS

Colliding

Worlds

REDEFINING

CONTEMPORARY ART

ARTHUR I. MILLER

W. W. Norton & Company New York London

W. W. Norton & Company New York London

Copyright 2014 by Arthur I. Miller

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Anna Oler

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Miller, Arthur I.

Colliding worlds : how cutting-edge science is redefining contemporary art /

Arthur I. Miller. First Edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-08336-1 (hardcover)

1. Science and the artsHistory20th century. 2. Science and the artsHistory

21st century. 3. ArtsExperimental methodsHistory20th century. 4. Arts

Experimental methodsHistory21st century. I. Title.

NX180.S3M555 2014

700.105dc23

2014005430

ISBN 978-0-393-24425-0 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

TO LESLEY

the visible; rather, it makes visible.

Paul Klee

ALSO BY ARTHUR I. MILLER

137: Jung, Pauli, and the Pursuit of a Scientific Obsession

Empire of the Stars: Obsession, Friendship,

and Betrayal in the Quest for Black Holes

Einstein, Picasso: Space, Time, and the Beauty

That Causes Havoc

Insights of Genius: Imagery and Creativity

in Science and Art

Imagery in Scientific Thought:

Creating 20th-Century Physics

This book has been a voyage of discovery for me. I was struck by how today, more than ever before, the world around us is being represented in a manner that combines art, science, and technology. I immersed myself in this new movement, which I call artsci, spending over a year conducting interviews in addition to visiting some of the essential centers devoted to it.

The many artists and scientists I feature in this book graciously took time out from their busy schedules for my interviews and replied to my queries with faster than light responses, as did directors and staff at key centers.

My deepest appreciation to all those artists who provided me with images of their work.

I thank my agent Peter Tallack of the Science Factory for his encouragement, enthusiasm, and sagacious advice.

Huge thanks to my editor at W. W. Norton, Matt Weiland, his assistant, Sam MacLaughlin, and their team, for their invaluable criticisms and assistance in the production process.

My appreciation to Allegra Huston for her splendid copyediting. Any errors that remain are my own.

I am indebted to my wife, Lesley, who has provided support and encouragement at every stage of this book. Her comments on the manuscript were invaluable, as always. This book is dedicated to her.

Arthur I. Miller

London 2013

www.arthurimiller.com

Colliding

Worlds

INSERT

O n October 13, 1966, the New York glitterati and all those who basked in their glow descended on the cavernous 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue to celebrate the opening night of 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering, the first ever large-scale collaboration between artists, engineers, and scientists. Ten artists and thirty engineers took part and the technology they used was spectacularly new at the time.

Naturally Andy Warhol, in sunglasses and leather jacket, was there, surrounded by his entourage. He was heard to declare, , but Im Susan Sontag. Marcel Duchamp, who had kick-started the entire modern movement in art, was there too, no doubt remembering the moment fifty years earlier at the 1913 Armory show when his Nude Descending a Staircase had scandalized New York. The up-and-coming artist Chuck Close sat next to Duchamp. The fashion designer Tiger Morse wore a bare midriff outfit of white vinyl with a portable lamp which bathed her in a violet glow.

Everyone involved agreed that Robert Rauschenberg was the inspiration but John Cage was undoubtedly the star. Cage, the composer famous for his 433four minutes and thirty-three seconds of intense silenceproduced a collage of sounds randomly collected at that moment by telephones around the city and the Armory. As the performance went on, one by one members of the audience stepped onstage to add to the cacophony, playing with juicers and mixers installed there.

The following night, Rauschenberg, the celebrated iconoclast and artist, showed a piece called Open Score, basically a game of tennis with the rackets wired to transmit sound. Every time a racket hit a ball, an amplified boing resounded around the building and one of the forty-eight lights went out, until the audience was in total darkness.

The performances were by turns magical and chaotic. It was an Andy Warhol moment, although very much inspired by Duchamp. The two served, so to speak, as bookends, Warhol as the logical conclusion of Duchampfrom the ready-made to the Campbells soup can. Everyone was sure what they were seeing was a brand new art movement that was going to blow a hole right through the middle of the traditional art sceneand they wanted to make sure they were in at the beginning. The opening night was a sellout, with 1,727 tickets sold; 1,500 people had to be turned away. In all, 11,000 people attended, with sellouts on three of the nine evenings. Everybody who was anybody, or had dreams of being somebody, was there to bask in the glow of the already famous. A New York Times reporter wrote of a sold-out performance, would turn off the whole New York art scene.

I n the nearly half century that has passed since that first explosion of excitement, art, science, and technology have rubbed up against one another in myriad ways. The resulting artworks have been sometimes beautiful, sometimes disturbing, sometimes subversive, sometimes downright crazy, but always interesting, new, and pushing the boundaries.

Colliding Worlds begins by taking the story back to the early days of the twentieth century, when inventions such as x-rays and photography transformed the way we see the world. Artists such as Picasso and Kandinsky took on board the latest scientific developments, while scientists found themselves driven by questions like the relevance of aesthetics to science and what makes a scientific theory beautiful. But it was not until the second half of the last century that the new movement, which has come to define the twenty-first century, really flowered, and it is this flowering that forms the bulk of my story. Its creators are artists and scientists working together to create images and objects of stunning beauty, along the way redefining the very concept of aestheticof what we mean by art and, eventually, by science.

I started to write about how art interacts with science and technology in the 1980s, when few people other than the artists and scientists themselves were taking note. Over the years I watched as more and more artists emerged, along with more and more art fairs and more and more conferences. I watched as the movement grew from something underground to something far more mainstream that impinges on our daily life, the realm of what we all take for granted.

Next page

W. W. Norton & Company New York London

W. W. Norton & Company New York London