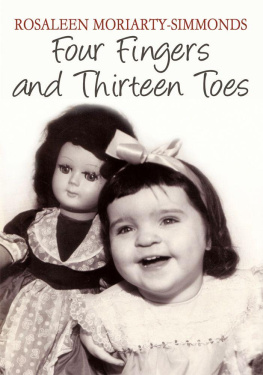

Four Fingers and

Thirteen Toes

Rosaleen Moriarty-Simmonds

AuthorHouse UK Ltd.

500 Avebury Boulevard

Central Milton Keynes, MK9 2BE

www.authorhouse.co.uk

Phone: 08001974150

2010 Rosaleen Moriarty-Simmonds. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the written permission of the author.

First published by AuthorHouse 1/30/2010

ISBN: 978-1-4490-8247-5 (e)

ISBN: 978-1-4389-4299-5 (sc)

22 Cyncoed Avenue,

Cyncoed,

CARDIFF. CF23 6SU.

United Kingdom.

Email:

Contents

In memory of my beloved mother, Ellen Philomena (Mena) Moriarty, who through her love, devotion and encouragement gave me the strength, courage and conviction to be who I am today.

The author would like to extend thanks to the following, who have helped and assisted in this publication:

Tim Richards, journalist and broadcaster, for his introduction to the book; The staff at the Thalidomide Trust for their assistance in providing statistical and historical information; Rebecca Sleeman for her help in designing the book cover; To Mark Cleghorn of Mark Cleghorn Photography, Cardiff, for portrait photography; All my Thalidomide impaired friends; The countless persons who have generously provided information and images on the Internet; To my family for all the stories and anecdotes that, I hope, make the book readable and enjoyable; And finally, to Stephen and James for being so patient with me, and without whose support I could not have completed this task. I am so proud of you both, and love you More than this much!

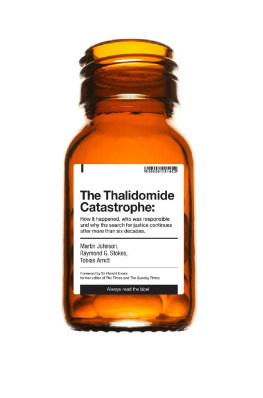

T halidomide was one of the horror words of the twentieth century. Along with Auschwitz, Aberfan and Chernobyl the very word Thalidomide still makes me shudder all these years later. It slaps me round the head with painful images of newborn babies without arms or legs. Just as mankind had been unspeakably evil in Nazi concentration camps or totally incompetent allowing a mountain of coal waste to destroy a Welsh school so for my generation of journalists working in the late twentieth century Thalidomide came to mean the cynical and callous cover-up of thousands of deformed births worldwide.

But that is simply the cruel public face of Thalidomide, a drug supposedly developed, amongst other things, to ease women through their pregnancies in the early 1960s.

Thalidomide became something much more personal for me in 1972 when I met a cute and confident little girl named Rosie Moriarty for a feature series I wanted to write for the Western Mail . From those first face-to- face interviews, and through several later meetings for BBC Radio Wales documentaries, I was able to watch a woman develop who though she had no arms or legs against all odds pushed herself through university in Cardiff and on to a professional career that has left non-disabled contemporaries trailing in her wake.

This story of Rosies isnt just about Thalidomide however cruel the physical results of that drug were. Rosies story is about guts and determination and intelligence and skill. Its one hell of an example to all of us!

Tim Richards

Journalist and Broadcaster

Four Fingers and Thirteen Toes

James - two days old having a quiet cuddle with Mum

H ello, James, my beautiful little boy, I mumbled, still drowsy from the anaesthetic. The hospital staff had brought him to me, swaddled up, with only his face showing. All I could see was a little pink face and a pair of blue eyes looking back at me. I glanced anxiously at the nurse holding him. She smiled and nodded reassuringly and I blanked out again, but with a feeling of relief.

It had not been a pleasant experience, and, had anyone bothered to ask me, I could have given them my opinion of the wonder of childbirth, an opinion that might have disillusioned many prospective mothers.

My consultant in the performance had been a strong advocate of natural childbirth, but, as he wasnt actually giving birth, I felt that he was perhaps not viewing the situation from the correct perspective. I quite fancied the idea of being knocked out and then later handed a nice, clean, pink baby; he had other ideas.

After some thirty-seven hours of the joys of labour, not much had happened, and I was becoming increasingly distressed and worried for my baby. The doctors then decided to do what should have been done in the first place. I was to have an emergency caesarean.

Until then there had been a happy air of expectancy among the staff, who were taking as keen an interest as I in the proceedings, but the arrival of the anaesthetist soon soured the mood. He refused to make eye contact with me and stood mumbling with his back to the window. He was supposed to be explaining the procedure he was about to perform, but, what with his mumbling, the lack of eye contact and the surrounding noise of the hospital, I understood nothing.

Could you come and stand at the foot of the bed where I can see you and hear you? I asked. Mumble, mumble, he continued, causing my husband Stephen to explode.

The anaesthetists attempts to give me an epidural were on par with his skills at communication and, after numerous failed attempts, the other doctors called in a senior anaesthetist, who, after a bit of prodding and poking, managed to get the drip inserted in my neck.

James was born at 8.42 p.m. on Thursday, 10 August 1995, weighing 7 pounds 2 ounces, a healthy, hearty baby eager to get on with the business of life.

The next day I was back in the regular ward, and James was in the little see-through plastic cot alongside my bed looking out at me and at the brave new world he had just entered. I looked back at him in wonderment. He was absolutely gorgeous and fascinating, and the love I felt for him was instant and intense. That warm glow of pride, love and devotion that only a mother can feel was mixed with a ferocious desire to protect, nurture and cherish. Nature and instinct are incredible things, and this normally wriggly little bundle of fun relaxed instantly whenever he was placed on me for a cuddle or when I held or carried him.

Six days later we arrived home to a house full of flowers, cards and good wishes from family, friends and acquaintances.

I doubt that there were three happier people in the whole world than Stephen, James and me. And then our joy was shared, if not quite so personally, by everyone that had known us through my pregnancy.

So whats so wonderful about all this? you say. Lots of women have babies.

But I was born with legs that ended above the knee and with no arms, just two fingers on each shoulder. Four fingers and thirteen toes in all.

It does make a difference.

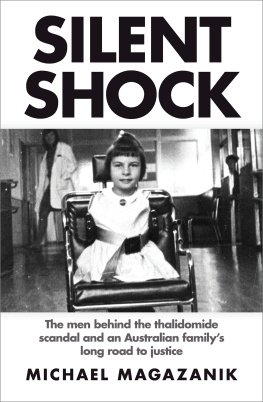

Otto Ambrose, one of Grnenthals directors in the early 1950s also a chemist and a director of IG Farben.

Dr Heinrich Mckter was the chemist in charge of the research at Chemie Grnenthal.

M ost people, when thinking of the Ruhr Valley in Germany, have a mental picture of heavy industry, steel works and smoking chimneys, an image which is not too far from the truth. And metal has been worked here since the seventeenth century, when copper was smelted and became the prime industry of the region. As with similar industry in Britain, the Ruhr had a nearby source of coal and became the heart of Germanys industrial revolution in consequence.

Next page