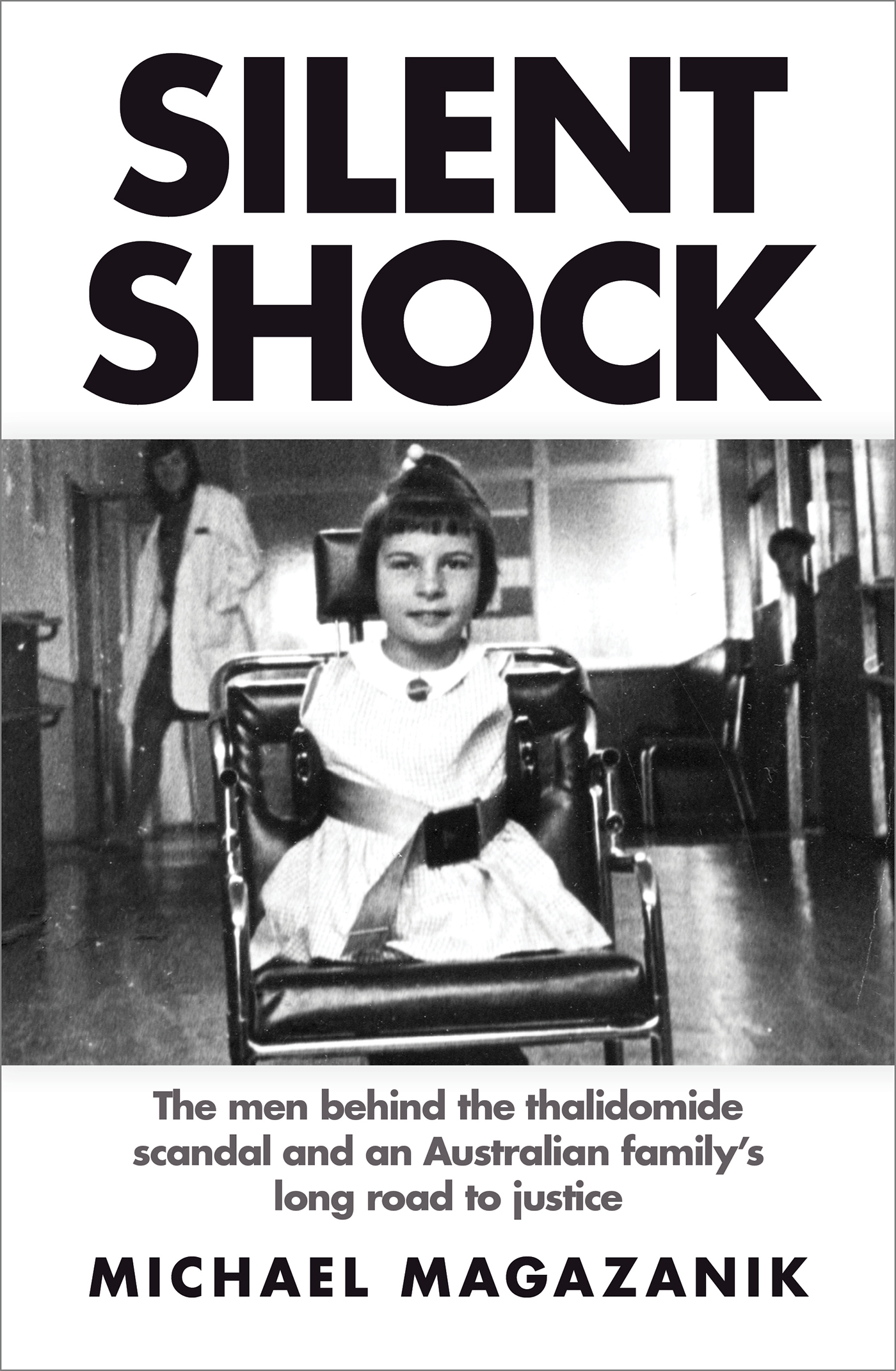

My thanks first to the Rowe family. Lyn, Wendy and Ian were not just the perfectclients, but patient and supportive when it came to the writing of this book (bywhich time they might justifiably have had their fill of lawyers, questions and intrusion).My respect and gratitude to them, and a large measure of heartfelt thanks to allthe other members of that remarkable family.

Mary Henley-Collopy, Monika Eisenberg, Monica McGhie, Barbara-Ann Hewson and theGordon family in New Zealand all took it on faith that their stories would be fairlytold. Many other survivors and and family members spoke with me over the years. Iam grateful to all of them.

Woody Woodhouse and Phil Lacaze worked for Distillers during the early 1960s andthen, fifty years later, helped us win compensation for survivors. They were willingand brave and always a complete pleasure to speak with. I am indebted to each.

There were many others who assisted in the litigation and/or in the research forthis book. A few without whom this account would be substantially lesser: Ron andAylsa Dickinson, Leslie Florence, Lance Fletcher, Phillip Knightley and the venerable,inestimable and indefatigable Ken Youdale, a great man whose life warrants its ownpublished history.

The modern Australian legal story is told in unavoidably short compass in these pages.Peter Gordon conceived of the thalidomide claim, an audacious and ambitious venture,and, by force of personality, breathed life into it. Im thankful for the invitationto join the team. The legal effort was, of course, a group effort, progress madefraction by fraction. The full team was Peter Gordon, Kerri OToole, Dael Pressnell,Sarah Roache, Patrick Gordon, Brett Spiegel, Grace Wilson, Lucy Kirwan, Julie Clayton,Paul Henderson, Andrew Baker, Caitlyn Baker, Amanda Barron, Kelly Hart, Jane Tarasewicz,Mariano Rossetto and Sasha Molinaro. Our barristers were Jack Rush, Julian Burnside,John Gordon and Andrew Higgins. Dr Sally Cockburn and Nina Sthle were also integralto the effort. Tosca Looby helped out in the crunch.

Peter Rielly, Campbell Rose and Jeff Kennett all played important roles in the charitableeffort to build a new home for the Rowe family when the result of the litigationstill hung in the balance.

At Slater & Gordon, managing director Andrew Grech backed the litigation andthen this book.

While writing I relied on family and friends for advice, encouragement and, frommany, a careful and wise reading. Thanks to Rob Lewis, Marcus Godinho, Lucy Kirwan,Jacinta Dwyer, Grace Wilson, Jeremy Blumenthal, David Blumenthal, Samantha Gee, CraigPasch, Shaan Beccarelli, Di Sarfati, Nina Sthle, the extended Joseph clan (especiallyRachel for the informal focus group) and the following Magasaniks: Simon, Lorraine,Ery and Laura. Neil Vargesson, Trent Stephens, Ravi Savarirayan and Sally Cockburnoffered insightful comments on parts of the book. Thanks to Chris Prast for litigationwisdom and to Ingrid Dewar and Tom Raabe for last-minute translations.

My appreciation to the team at Text, especially my editor Mandy Brett for grace underpressure and precise, brilliant work; and to publisher Michael Heyward for backingthe project.

To all I have overlooked in this last-minute rush, my apologies.

Which leaves two final votes of thanks and love. My parents Ariel and Daniel, forreading, editing and commenting on every word of a rough first draft of every chapter;and for their (sometimes) optimistic faith in me and for much, much else besidesover many years. And finally (and inadequately) to Nicole, partner, lawyer and non-fictionadviser: for unstinting love, encouragement and patient counsel, even as the fouryears of litigating overand writing aboutthalidomide coincided precisely with thearrival of our children: Asher, Jonah and Zara. My deepest thanks and love.

Silent Shock, inevitably, draws heavily on research and interviews conducted in supportof Lyn Rowes legal claim between 2010 and 2012. Once this book got off the drawingboard, much further research and many more interviews (including follow-up interviews)were conducted. Many people, as is clear in the text, were exceedingly generouswith their time. The documents referred to and quoted from in the text come frommany sources, and these sources are often made explicit.

The legal team was able to inspect documents held by the Sunday Times, the Nordrhein-Westfalenstate archive (then in Dsseldorf, now in Duisburg), the National Archives and NationalLibrary in Canberra, the National Archives in New Zealand, the United States Foodand Drug Administration, and various libraries in Australia, the United States andthe United Kingdom.

Lyn Rowes legal team also received (gratefully) valuable documents from thalidomiders(or their family members) in several countries. One such early document was a highly-prizedcomplete copy of the German prosecutors 1000-page indictment. Other important documentsrelated to the litigation in the United Kingdom and Australia in the 1960s and 1970s,plus a number of newspaper clippings collections kept by affected families.

After the conclusion of the litigation I was very fortunate to access one further,and especially valuable, store of documents. Elinor Kamath, an American woman, wasworking as a medical correspondent in Germany in 1961 when the thalidomide disasterbecame public. Multilingual, curious and extraordinarily bright, Kamath embarkedon a twenty-five-year study of the medical aspects of the disaster. Later, whileworking at Stanford University, she won funding to turn her investigation into abook. During the 1980s Kamath interviewed Leslie Florence, the Scottish doctor whomigrated to New Zealand and who had published on thalidomides neurotoxic effectin 1960. In 2012 Florence told me of Kamath and her work, but after inquiries Ifound Kamath had died in 1992. Then in 2014, by chance, I found on a book-sales websitesome proposed chapters Kamath had prepared for a potential publisher. Somehow thirtyyears later they had ended up for sale. I bought them, and, following clues, eventuallyfound Kamaths nephew Chris Kahn. He was first curious and then enormously helpful.In June 2014 I flew to the US to spend a week looking through the thalidomide treasuresKamath had assiduously assembled over a quarter of a century: contemporary documents,interviews with key players, trial transcripts. My only disappointment was for ElinorKamathdespite all her effort she had never seen the publication of the book shehad provisionally entitled Echo of Silence. In some key areas Silent Shock drawson Elinor Kamaths work, and tribute is paid to her here.

Some other sources of material included the FDAs oral history projectmany interviewtranscripts are accessible via the agencys website, including with some of the participantsin the thalidomide affair and its legislative aftermath. A number of the importantactors in thalidomide, principally Frances Kelsey, Widukind Lenz and Bill McBride,have left voluminous records, all of which were useful in recounting their roles.

Some other matters of note. In a very few places full names have been omitted. Thishas been done to protect the identity of thalidomide survivors who have not beenprominent publicly and who may not have wished to be identified. In several placesthat meant using an initial only for a parent: i.e. Dr K, Mrs H etc.

Malformation is one of the most-used words in this text. Fifty years ago the chosenterm was deformed or deformitywords still used today but certainly not embracedby thalidomide survivors or by the disability community more broadly. The word deformedand its variations have only been used when quoting, or because of context.

In accordance with Australian usage, the spelling foetus has been used throughoutagain,except when quoting documents in which the medical (and American) spelling fetuswas used.

Next page