An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2015 by Jane Singer and John Stewart

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4930-0810-0 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4930-1738-6 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

For James Martin Singer

For Gayle Winston

Contents

Introduction

If this were played upon a stage I could condemn it as an improbable fiction.

Twelfth Night: act three, scene four, by William Shakespeare

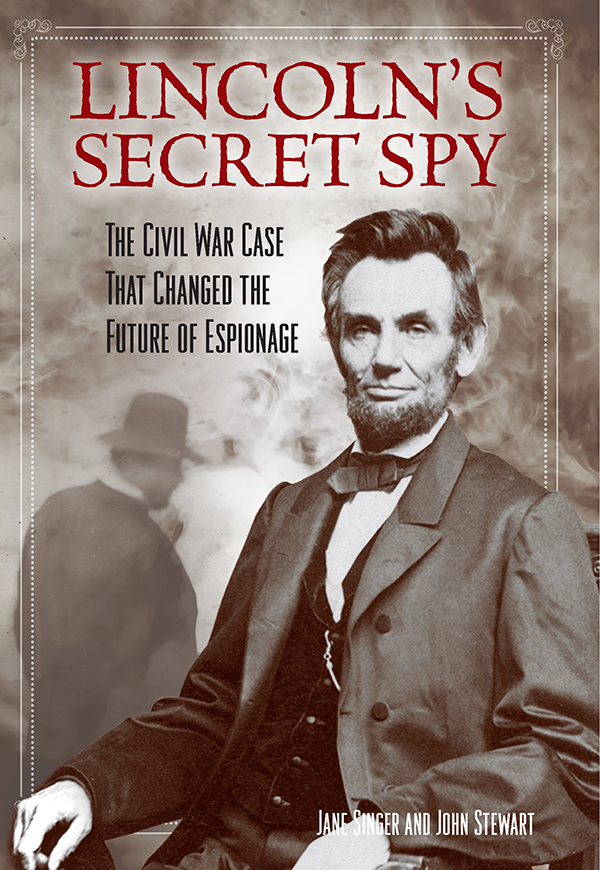

William Alvin Lloyd. Here was a man, a comet, streaking through decades with impudence and impunity. A simmering broth of lust, indefatigable energy, greed, and larceny, he was magical, priapic, musical, inventive, a survivor and a scoundrel. From a jangled, jarring Kentucky boyhood where he learned a tailors trade, he then ran from that trade, covering his dye-stained hands with white gloves, and, on occasion, his face with the burnt cork of the minstrels, his minstrels. For a time Lloyd owned the tambos, the bones, the banjos, and the men that played them. He was a publisher, a blackmailer, seeking scandal, a moth to a fire. And in the war, his time in the war was at first a salvation that brought him a little wealth then stripped him bare, disarmed and desiccated him. Then accused, nearly hanged as a Union spy by the men who ruled Dixieland, the land hed loved.

At the end of the war, no longer a comet but a mere spit of light, he crawled away from the rubble of that land to emergetwisted, numbto reconfigure, to proclaim that he was Abraham Lincolns personal secret agent throughout the Civil War. Was William Alvin Lloyd truly Lincolns own, or a cunning imposter? And his lawyer, Enoch Totten, who for years doggedly pursued Lloyds claim until it became the basis of an important Supreme Court precedentone that to this day affects the legal rights of clandestine operatives and assetswas he the architect of a great fraud?

Authors Jane Singer and John Stewart have both written books about the Civil War and are devoted students of spy craft, priding themselves on prying secrets from the jaws of a murky trade that rarely succumbs to hard research. Tracking the oft mentioned but never researched William Alvin Lloyd through private collections, genealogical sites, old newspaper article databases, the National Archives, the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, and numerous historical societies was revelatory. Finally after scouring unpublished primary source documents, witness testimonies, and court transcripts, the true story of his claim and of a life writ large emerged. But in spite of our inescapable conclusions we were, and still are, riveted by the tireless moxie of the man. And though he might howl to learn that two twenty-first-century authors have shone a hard light on his long-hidden secrets, he could not help but applaud his top billing. William Alvin Lloyd is onstage again. But this time he is truly the star of his own show.

I Was the Presidents Spy

Washington City

Through an old stereoscope viewer, caught in a photographers explosion of black powder and flashes of light, see a man. Though featureless, note that he is on his last legone is shriveledbarely allowing him to stand so he must lean on makeshift crutches, crude wooden rods that steady him. He fades, blurring as he inches painfully along. He will stumble, right himself, and at times like this, slip from view.

But there are factsnot unwarranted colorizationsaccompanying William Alvin Lloyd. Know he has endured harsh imprisonment and bears the scars of a near-fatal shooting. Know he has hobbled out of the ravaged Confederacytorn sinew and aching bonesto the depot at Danville, Virginia. There he boarded a shuddering night train that took him to Richmond, then by rail and steamer to City Point, Virginia, and finally into the nations capital.

But as sorry a sight as he is, unlike the masses of maimed and scarred Union veterans flooding the city, William Alvin Lloyd is no ordinary soldier. He is a man on a mission. He has secreted a packet of documents on his person. And he is armed.

If all goes according to plan, Lloyd will make his way to the War Department and seek an audience with Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, who is headquartered there. But he will not kill the enemy chieftain whose mighty armies defeated Lees forces. Rather he has come to wound the Yankee government and make it bleed. Money. A great deal of it. The documents he clutches, he hopes, will prove that he has been President Abraham Lincolns secret agent in the Confederacy. His timing is perfect. There could be no firm handshake from the president Lloyd said employed him. The dead dont shake hands.

While there is no record of Lloyds meeting with Grant at his War Department office, it is fact that his documents were received and examined by someone on the busy generals staff. So we must envision Lloyd entering a nearly empty building and leaving the papers with a clerk, perhaps an indifferent drudge who tosses them on a pile and rushes off to the parade, the Grand Review of Union Armies, an immense and imposing display of men and weaponry.

It is May 24, 1865, three weeks after the assassination of President Lincoln. The moist, heavy air of the preceding dayssorrowful days of endless mourning for the Presidenthas lightened, dried, and cooled. Black cloths that draped the Capitol like giant widows weeds have been removed. Flags, once at half-mast, now flutter in ruffles of summer wind. President Andrew Johnson has ordered this day and the next to be one long celebration, a welcome respite for the denizens of the city who crowd rooftops, peer excitedly from windows, and pack the streets. Hearty huzzahs echo through alleyways, over the fetid canals, and up Pennsylvania Avenue. Banners, foodstuffs, horse dung, and spent cartridges litter the cobblestones as do the drunks, whores, and beggars whove flooded the city since the first of the regiments came by train and horseback to march as one for the last time before returning to civilian life.

I saw the day the return of the heroes, Walt Whitman wrote after watching the parade from somewhere in the crowd. I saw the interminable corps, I saw the processions of armies, worn, swart, handsome, strong.... No holiday soldiersyouthful, yet veterans...

Gaze at a sea of bonnets, straw hats, and top hats, and below them, know that if William Alvin Lloyd does cheer with the masses that have gathered to watch a quarter of a million Union victors, he will do it for show. And does he see in the reviewing stand, just opposite the White Houseseated in the canopied wooden bleachers along with President Andrew Johnson and his cabinetLieutenant General Grant, smoke from his ever-present cigar clouding his face as his victorious troops parade before him?

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.