For Smiler, JDU, Nibby, Iscariot, Inchy and friends

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

PEN AND SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Charlotte Zeepvat 2015

ISBN 978 1 78346 375 6

eISBN 9781473846791

The right of Charlotte Zeepvat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in Times by CHIC GRAPHICS

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

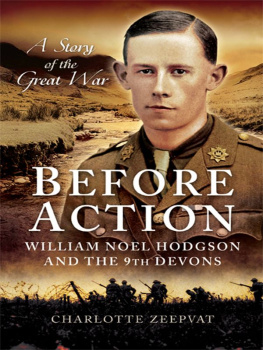

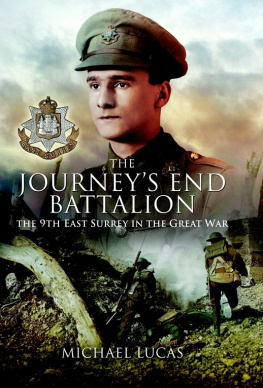

There was a time when William Noel Hodgson was one of the most celebrated poets of the Great War, named alongside Brooke, Sassoon, Graves and owen. Letters in the archive of his publisher and newspapers of the 1920s and 1930s bear witness to the number of times his poems were reprinted, broadcast especially on Armistice Day even set to music (they lent themselves to music rather well). He wrote about places that mattered to him, hills most of all; about ideas and dreams and hopes, sometimes about sadness. He had a neat touch with comedy too, though few of his funny poems ever saw print. When war came his voice was distinctive, setting the crisis of the day into the long perspective of history. He was no fan of war, but accepted that particular war with resignation as something that must be faced and fought, and this was an attitude his contemporaries understood. Most shared it. His poems touched readers, none more than the last, Before Action, a prayer for courage in the face of death which he wrote shortly before he was killed on the Somme.

It was in the 1930s that things began to change. A generation too young to have fought and tired of hearing about the war would gladly have cut war poetry altogether. In a Times Literary Supplement article in December 1943, the playwright and critic Charles Langbridge complained of war poetrys exclusion from Yeats 1936 Oxford Book of Modern Verse. He singled out three poets who should have been included: Charles Sorley, Wilfred Owen and William Noel Hodgson.

At the same time, as the sorrow and pride of the early post-war years gave way to a deepening bitterness, fuelled by the political divisions of the day, so the poets who had expressed anger and bitterness at the war began to take precedence. By the 1960s this had become a matter of definition: war poetry was supposed to be about protest. Mud, blood, tears and futility. To be worthy of consideration a poem had to be on message. Those that were not most of the poems published during the war, in fact were dismissed as being at best irrelevant, at worst, part of the mindset that had come to be blamed for the war itself. In the meeting of these two strains of thought, Noel Hodgson fell from favour.

But history stepped in to keep his name alive. Whatever the literary world might say of his poetry, his last poem made him one of the best-known casualties of the opening hours of the Battle of the Somme, a tragedy which has never ceased to haunt the British imagination. Interest in the story was revived in the 1970s thanks to a powerful and successful book, Martin Middlebrooks The First Day on the Somme. Middlebrook described how Hodgsons battalion had known that their advance that morning would be exposed to fire from a particular German machine gun, thanks to a relief model made by Captain Martin, one of their company commanders. But Martins warning was dismissed by his superiors; Middlebrook saw Hodgsons Before Action as moving proof that he and others believed Martin and knew they faced certain death. The story has been embellished down the years and much of it does not stand close scrutiny, as this book will show, but thanks to its existence Noel Hodgson became a name at once known and unknown, familiar to both camps, literature and history, but with almost no attention paid to his life. In common with so many of his generation he was remembered for dying, and for knowing that it was likely to happen.

And that is a shame, because in life Noel Hodgson was cheerful, sociable and easy-going. He enjoyed hill-walking, rugby, cricket, hockey, tennis, running anything active and was good at them too. He had an intensely private side which he kept for his writing; few of those round him were even aware of it. But he was not content to keep his writing a private hobby; he wanted to write for publication. War gave him a subject and it made his name. It also took away whatever chances he may have had.

This is his story. And because, for reasons that will become apparent, there would be no story without his family, the book is their story too. His experience opens a portal into the worlds he knew: of family life before the war; of school and university, most of all, of a 1914 volunteer battalion, in training and in France; their experiences good as well as bad brought back to life in their own words. Hodgsons life is the thread that links these lost worlds. Through them, the book becomes a story of the Great War itself.

Acknowledgements

Before Action has been over thirty years in the making and several people who helped in the early days did not live to see the end result; I hope they would have approved.

The most significant missing piece in Noel Hodgsons story is his parents papers. No one knows what became of them. His sisters papers proved invaluable. This book could not have happened without the help of Henry and Penelope Hodgsons descendants, especially Christopher and Adam Balogh, Susan Ashmore, Christopher Hodgson and Tirril Harris. All the family members I have contacted over the years have my heartfelt thanks for their willingness to help, their knowledge and their patience. Im particularly grateful to Christopher Balogh and Christopher Hodgson for permission to use photographs and documents in their possession. In the same way, it would have been impossible to describe the experiences and characters of the 9th Devons without the generous help of William Upcott his grandfather JDU really deserves a book in his own right Paul, Martin, Richard and Patrick Wollocombe; Paul, John and Russell Freeland. Paula Richardson kindly shared her grandfather Alan Hinshelwoods photograph album and gave permission for the use of his sketch; Dorothy Parr shared her memories and Geoffrey Mason allowed me the use of three letters to Robert Parr that he found in a second-hand book.

I am also grateful to the following for permission to quote from material in their collections or to which they own the copyright: the Provost and Fellows of Worcester College Oxford [Oxland]; the Special Collections Research Center, Morris Library, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale [Inchbald Brothers Collection]; the National Library of Scotland [John Murray Archive]; the Westminster School Archives [George Hodgson]; Leeds University Library, Liddle Collection, [Pocock and Wide]; The Keep Museum [W.J.P. Aggetts The Bloody Eleventh ]; Clara May Abrahams [May Wedderburn Cannans Grey Ghosts and Voices]. While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders, in some cases this proved impossible. The publisher and I would welcome information from anyone who believes their material has been used without due credit.

Next page