Copyright 2010 Grant Lawrence

2 3 4 5 14 13 12 11 10

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, .

Harbour Publishing Co. Ltd.

P.O. Box 219, Madeira Park, BC, v0n 2h0

www.harbourpublishing.com

Edited by Silas White.

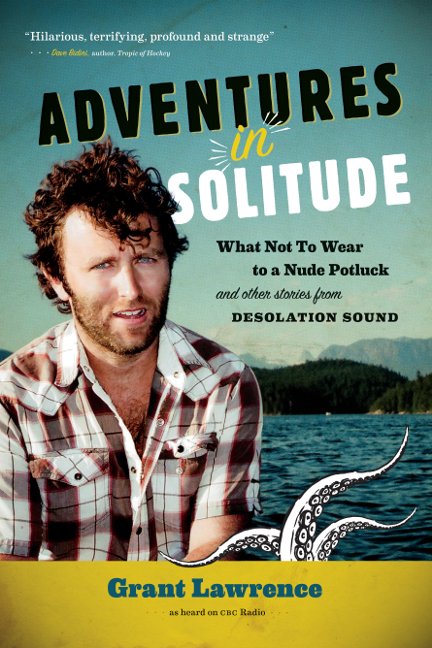

Cover design by Naomi MacDougall. Cover photograph by Julie Mendgen. Back cover photo by Megan Barnes. Inside cover: Detail from A Chart shewing part of the Coast of N.W America with the tracks of His Majestys Sloop Discovery and Armed Tender Chatham ; Commanded by George Vancouver Efq. and prepared under his immediate inspection by Lieu. Joseph Baker, courtesy David Rumsey Map Collection, www.davidrumsey.com. All interior photographs from the authors collection, with the following exceptions: table of contents, Ken Kelly; page 25 by Nadine Sander-Green; page 102 from the collection of Andrew Scott; page 196 courtesy Richard Blanchet; page 102 by Chris Kelly.

Illustrations by Christy Nyiri. Interior design by Five Seventeen.

Printed on 100% post consumer waste recycled stock using soy-based inks.

Printed and bound in Canada.

Harbour Publishing acknowledges financial support from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

library and archives canada cataloguing in publication

Lawrence, Grant, 1971

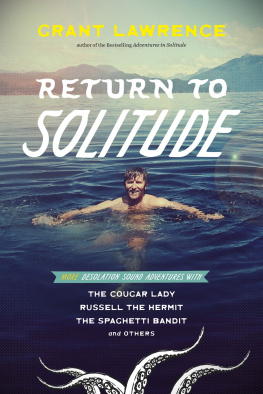

Adventures in solitude : what not to wear to a nude potluck and other stories from Desolation Sound / Grant Lawrence.

Includes bibliographical references.

isbn 978-1-55017-514-1 (paper)

isbn 978-1-55017-647-6 (ebook)

1. Lawrence, Grant, 1971.

2. Radio broadcastersCanadaBiography.

3. Desolation Sound (B.C.)BiographyAnecdotes.

I. Title.

fc3845.d47l39 2010 971.1'31 c2010-904401-0

for Dad

Prologue

I t was nearing the end of another gorgeous day in Desolation Sound. Nick and Soraya were busy cooking our annual long-weekend seafood feast: grilled lingcod, steamed clams, boiled red rock crab, barbecued oysters and skewered prawns, all caught within the last two days in the surrounding waters. I volunteered to make a last-minute check of the prawn trap, to top up our menu of the freshest food in the world. Climbing into the boat, I looked into the clear, bottle-green salt water and saw the reflection of my face: relaxed, unwashed and grizzled from weeks in the w ilderness.

There was no place I would rather be. The eighteen-year-old Mercury outboard managed to start up one more time, on the third pull. I plunked myself down on the salt-encrusted bench seat, cracked an almost-cold Black Label beer and opened up the throttle. Speeding through the inlets main current while squinting with my hand over my brow at the reflective ocean surface, I eventually spotted the Styrofoam buoy with Lawrence scrawled on the side of it. I slowed down, pulled alongside and, in one tipsy motion, killed the engine, reached over the side and grabbed the buoy rubbing against the skiffs beat-up aluminum hull. I hopped to my feet and started hauling the trap up from the bottom of t he ocean.

Prawning in coastal BC waters generally calls for a depth of about three hundred feet. Thats the height of a thirty-storey skyscraper, pointing straight down. I kept pulling, hand over hand, the workout and the warmth of the setting sun causing a trickle of sweat down the back of my neck. After a few minutes of heavy hauling, the two-pound weight marking two hundred feet clanked against the side of the boat like a mallet to a gong. In another minute or so the trap was at last visible, now just twenty feet below in translucent j ade water.

The ocean let go of the trap with a righteous splash. Much lighter without water holding it down, I hauled the trap over the side and onto the floor of the boat. On a good haul, the trap is alive with chaos, prawns snapping their Sea-Monkey-like forms in every direction, their scales a bright pink, their tiny eyes black and bulgin g .. . But on that midsummers eve, the contents of the trap moved slowly, thickly as one mass: a living lava lamp. A mound of red, pimply slime rolled over against the mesh, revealing a large, menacing yellow eye glaring back at me. I stumbled backwards, sloshing beer onto my dir ty shorts.

I was staring into the eye of the great Pacific octopus, the first I had ever seen in the wild, filling my prawn trap with its red, lumpy skin and intertwined gelatin arms. Without taking my eyes off it, I nervously cracked a fresh beer with one hand; with the other, I reached around for my fishing knife but found only the emp ty sheath.

Never that comfortable with large wild animals, I wanted the octopus out of the boat as fast as possible. I reached forward and flipped the release catch, causing the trap to spring open. The octopus slid out onto the floor of the boat like spilled Jell-O, sending me scrambling in panic up to the very edge of the bow. The eight-armed beast made for the opposite end, still glaring, gills flaring, tentacles outstretched, feeling up its foreign surroundings in every direction.

While I stared on in morbid trepidation, one of the octopuss tentacles crept out to the right to wrap itself around a wrench I occasionally used to bang-start the outboard. Its eyes were locked onto mine as another tentacle slithered out to the left, feeling around the floor of the boat like someone looking for their glasses on a bedside table. To my horror, the octopus found my fishing knife before I could, loose amid fishing tackle and empty beer cans. The octopus appeared to be arming itself and it had six a rms to go.

My eyes darted around the bow for something I could protect myself with. The octopus began to advance, slithering like Jabba the Hut in my direction. Then I saw the oar, seven feet long, lying lengthwise along the side of the boat. I snapped myself out of my frozen fear and grabbed it, pointed it at the octopus, and went over my options. I didnt want to kill it; I wanted it to return to its octopuss garden beneath the waves. Instead of positioning the oar as a club, I fashioned it more as a giant spatula. I edged forward and, with one thrust, slid the blade of the oar under the octopuss body. The octopus paused, its eyes widened, then it dropped its weaponry and wrapped all eight arms around the oar like a little girl hugging her dad dys leg.