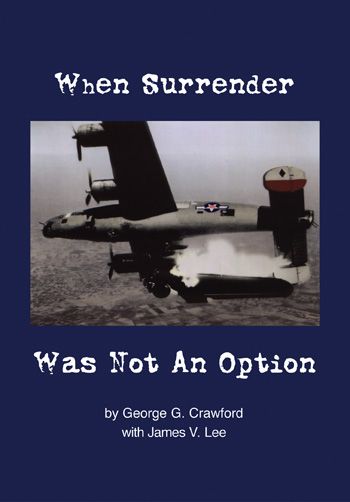

When Surrender

Was Not An Option

Copyright 2001 George C. Crawford

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without permission in writing from the publisher, except be reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper.

ISBN 0-9663870-3-1

LCCN 2001 126665

P. O. Box 852011

Richardson, Texas 75085-2011

Dedication

This story is dedicated to the memory of Captain Azorin, M.D., the senior French officer of the Slave Labor Camp, for keeping me alive during troubled times and to Colonel Spivey and to General Vanaman for leadership inspiring me to harass the enemy, yet survive.

Photo Courtesy American Airpower Heritage Museum, Inc.,

Midland, TX

Introduction

When Surrender Was Not An Option is the dramatic World War II account of 2nd Lt. George G. Crawfords experience as a prisoner of war in Nazi Germany from the time his B-24 bomber was shot down until his liberation and return to the United States. It is a saga of men on the cutting edge of courage who didnt just endure a long Nazi nightmare. Rather, in the best tradition of U. S. military duty, George and his fellow captives resisted and harassed the enemy in every way possible. By elaborate escape methods, they diverted thousands of German troops who otherwise would have been on the fighting front. Although his captors temporarily emaciated his body, they failed to extinguish his indomitable spirit, which serves as an example and inspiration to all Americans.

Jack W. Tarbutton

2nd Lieutenant, U. S. Army Air Corps

Pilot, B-26 Bomber

12th Air Force

Nazi POW from October 1944 to April 1945

Stalag Luft III

Chapter 1

The Last Mission

We had a rough mission that day bombing the Monte Abbey Cassino. Flak filled the sky, but for the first time, the 456th Heavy Bombardment Group dropped all bombs at the same time the lead bombardier dropped his bombs. Saturation bombing.

Bombing of Monte Abbey Cassino

Photo Courtesy of Fred Riley

Our Commanding Officer thought his bombardier could do no wrong. Of course, the C. O. was a little prejudiced, since his bombardier spent most of his time sucking up. Personally, I thought the lead bombardier was blind in one eye and couldnt see out of the other. The Monte Abbey Cassino mission proved me right.

We had had a good briefing for the mission with excellent pictures of the target. The Abbey sat on top of a mountain with a river on one side and a railroad on the other. A large problem was the forest of flak guns around the Abbey that the Germans were using as a command post. We had a clear sky and good visibility, except for all the exploding shells.

Still, our lead bombardier couldnt find the target! We were getting all shot up as we followed the C.O.s pet in a cloverleaf pattern around the Abbey until he could find the target. Finally, the blind man found the Abbey and we plastered the target and returned to our home base looking like a bunch of cheese graters.

After landing at our base at Foggia, Italy, we learned that the German Command and all troops, except the anti-aircraft gun crews, had taken shelter in the caves, catacombs, and basements, thus not suffering any casualties from our bombing. When our ground troops went up the hill, they not only got shot up, but were driven back a few miles.

Our planes were patched up that night, but the damage was so great that the flight crews got the next day off. After sleeping late and having breakfast in the mess tent, I went to the flight line to see how the repairs were going on our plane. We really had been lucky, as there wasnt too much damage, and only our flight engineer had earned a Purple Heart. I climbed into our plane to check out the bomb release mechanism. Some of the planes in the 456th Group had bomb releases that malfunctioned or had bomb bay doors that did not open wide enough.

Suddenly, I found myself thinking of For Whom the Bell Tolls and Hemingways description of the smell of death. The odor of our plane fit the description exactly. I looked for something dead or dying but found nothing, just that overwhelming, evil odor. I asked the ground crew if they smelled anything rotten, but I was the only complainer. I checked out the bombsight in the nose, and then I knew. I was certain that the odor was a warning that not all of us were coming back from our next mission.

The premonition grew stronger. What could I do about it? Was I going only one way next time? Was my wife going to be a widow? I didnt think that would happen, but I knew that not all of our crew would make it back the next day. I then reviewed the manual on emergency procedures and made certain that the release handle on the nose wheel door operated smoothly and didnt hang up. That might be my exit in case of trouble.

What should I do? Should I tell the rest of the crew of my concern? I decided against that, as it might cause some of the crew to get nervous and really screw up. I did write my last letters to my wife and to my dad telling them how much I loved them. I also told my wife not to be a professional widow but to get married soon because she was too good to go to waste. Then I ate an early dinner and went to sleep with my parachute as my pillow. I wanted to be certain it would be in good shape tomorrow.

After an early breakfast the next morning, we went in for our briefing. The mission looked pretty good another raid on Vienna, Austria. Our raid there last week had been a long trip, but a real milk run. No fighters and no flak. Then the weatherman told us the target might be socked in. Lots of clouds. Our secondary target would be Klagenfurt, Austria on the railroad marshalling yards that had never been hit before. That might be another milk run. Good news, but I knew better.

Then it was out to the flight line where our plane was gassed up and holding a full load of 500-pound G.P. bombs. Our four engines roared to life. All systems checked out O.K., but I still smelled death all around me. Next, we taxied around on the steel mats that kept us from sinking into the Foggia swamp on our base. Suddenly, we ran off the mats and sunk up to our wheel hubs into that awful muck.

I was delighted! We couldnt go on this damn mission! Our crew was safe from death, or worse. Other planes had run off the mats before, and it always took at least a day to dig them out. There was no way we would be able to fly this mission. Quickly, the ground crew came out with a little tractor. I grinned. That little tractor couldnt get our heavy plane out of that muck. The tractor driver hooked onto the nose wheel, revved up his engine, and popped us right up and out of the mud and onto the mat. I couldnt believe it! This couldnt have happened, but it had. Now there was nothing to do but sweat.

We took off and headed for Split, Yugoslavia. I told Lt. Morris Turitz, the navigator, to wake me up if we ran into trouble or when we approached Vienna. Then putting my head on my parachute, I went to sleep. No use worrying about the future now. Fate was, I knew, against us.