SHOT FROM THE SKY

The latest edition of this book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2003 by Cathryn J. Prince

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Prince, Cathryn J., 1969

Shot from the sky : American POWs in Switzerland / Cathryn J. Prince.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-6125-1347-8

1. World War, 19391945Prisoners and prisons, Swiss. 2. World War, 19391945Aerial operations, American. 3. NeutralitySwitzerlandHistory20th century. 4. World War, 19391945Switzerland. I. Title.

D805.S78P75 2003

940.5472494dc21

2002153476

10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

First printing

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are courtesy of the Swiss Internees Association Inc.

For the airmen

CONTENTS

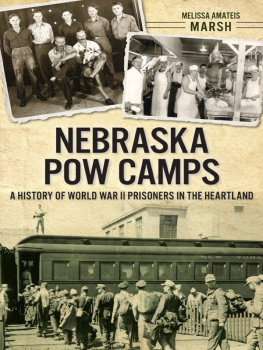

This book is about one of the great dark secrets of the Second World War. From 1943 until the end of the war, Switzerland shot down American aircraft and imprisoned the surviving airmen in internment camps. The Swiss military detained more than one thousand American fliers between 1943 and 1945. Conditions at the internment camps were adequate and humane for internees who obeyed their captors orders and did not try to escape. These internees were held in vacant hotels in small mountain villages and were allowed to interact with the villagers. The internment experience was very different, however, for the hundreds of airmen who tried to escape: those who were apprehended were held in appalling conditions in special penitentiary camps. One camp in particular, the infamous Wauwilermoos, kept Americans in conditions as bad as those in some prisoner-of-war camps in Nazi Germany. Ironically, the airmen could not demand better treatment under the Geneva Accords (precursor of the Geneva Convention) because at that time the accords did not apply to prisoners held in neutral countries.

I moved to Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1995not by choice, but because my husband, then a Swiss citizen who had come to the United States on a J1 visa, had to return to his home country for two years before he could be eligible for a green card. Six months after we married I left my job as a reporter for a Boston business newspaper, my family, and my friends to move to a place where I had previously spent all of two hours.

As our moving date approached, I contacted many U.S. newspapers and magazines to advertise my services as a stringer. Time and again I was answered with the same mantra: Nothing happens in Switzerland, but heres my number if you want to keep in touch. Then, about a month before we were to leave, I met with editors at the ChristianScience Monitor who were eager to have a correspondent in Switzerland to cover both domestic affairs and the United Nations.

I must confess that I had no inkling of the complexities of Swiss society before I arrived. Switzerland had always seemed to me a bastion of multilingual and multicultural harmony content to remain uninvolved in European affairs. Almost immediately I learned how far from reality was this view. Soon after we arrived I began immersing myself in Swiss politics, meeting with key officials from Switzerlands political parties, trade organizations, and social groups. I was accredited to the United Nations in Geneva, and soon I was filing reports nearly once a week from a country where nothing happens.

I saw European Union flags snapping in the breeze in the French-speaking part of the country. In German-speaking Switzerland, however, save for some of the larger cities, I witnessed much resistance to the notion of joining a greater Europe. The country was starting to question the value of neutrality at a time when the world was becoming increasingly interconnected. Not only did the Swiss argue about joining the European Union, but during my two years there they questioned what role to play in NATO and whether to allow NATO aircraft to overfly Swiss airspace to bomb targets in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

I had been in Switzerland for nearly a year when the first sparks of the Nazi gold crisis ignited and Senator Alfonse DAmato of New York began taking the Swiss banks to task for their ignoble practices during the Second World War. Suddenly, journalists, particularly American journalists, were not held in great favor. I had, however, been diligently reporting the domestic affairs of Switzerland for some time and had cultivated a great many contacts. These people helped me as I reported the bank situation, but they proved even more important as I embarked on what turned out to be an extraordinarily compelling story.

It is because of my father, a physician, that I am deeply interested in Switzerlands actual role in World War II. He was a captain in the U.S. Air Force, served as a flight surgeon in Vietnam, and is a history buff. I mention these facts because they influenced the course of study I pursued. I have always been fascinated by the history of war and diplomacy and the role of aircraft in war, and when he recounted a story from one of his patients, I was finally able to embark on a project that would meld my interests.

The patient, David Disbrow, told my father that the only way he would ever return to Switzerland would be in a bomber. Disbrow had been a waist gunner in World War II. His plane crash-landed in Switzerland, and he was caught trying to escape and sent to a Swiss prison camp. He tried to escape again, and at the border Swiss guards shot one of the men accompanying him. That is the extent of the story Mr. Disbrow told my father. I was intrigued by this forty-five-year-old account, having never seen any reference to American airmen being interned in Switzerland during World War II. The ramifications of such a storyneutral Switzerland shooting down U.S. aircraft and interning U.S. servicemenwould be enormous if true, I thought.

I began my investigation by contacting Jrg Stssi-Lautenberg, the director of the Swiss Military Archives and an excellent source of help and information. He had heard that American pilots had been interned in the country, but the Military Archives did not have the records I sought; they were in the Federal Archives. To help get me started, Stssi-Lautenberg introduced me to Peter von Deschwanden, the mayor of Adelboden, whose own father, a physician, cared for many interned U.S. fliers during the war. Von Deschwanden met me in Bern, and we talked about what it was like when the Americans came to Adelboden. He agreed to take me to the village and introduce me to people who had known the Americans. Through him I met and interviewed many Swiss civilians and retired military personnel who had known the interned fliers. An octogenarian owner of a ski store recalled imprisoned Americans whizzing down the slopes and breaking legs in winter and hiking in the spring to scout for escape routes. American airmen constantly attempted to flee Switzerland, risking arrest and imprisonment in camps run by Nazi sympathizers.

Next page