Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

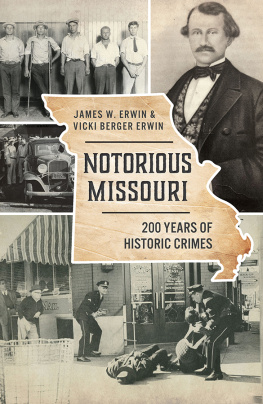

Copyright 2018 by Vicki Berger Erwin and Bryan Erwin

All rights reserved

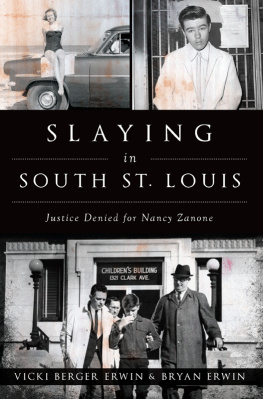

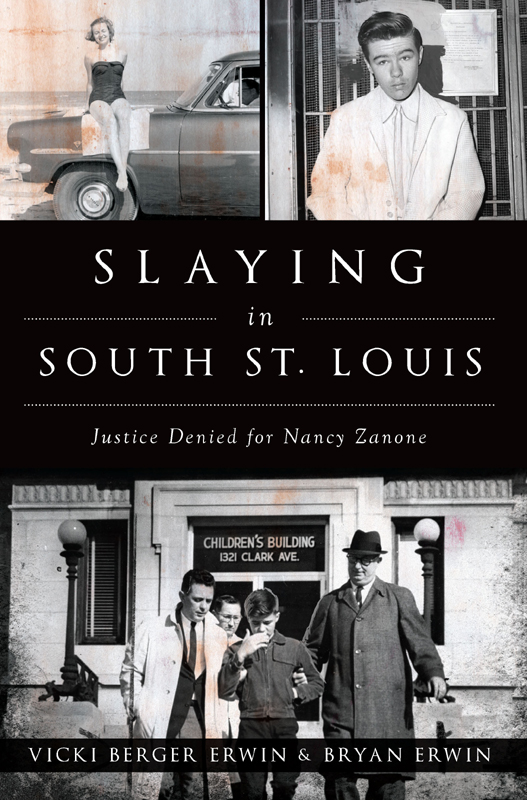

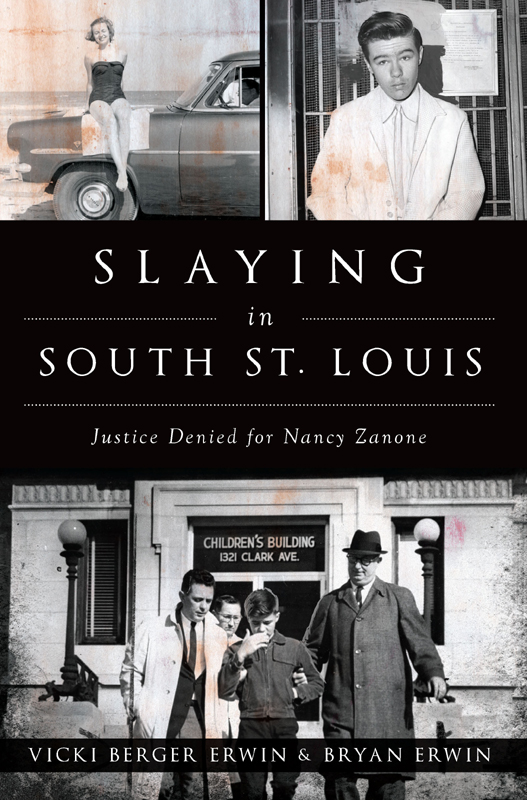

Front cover, top left: Zanone family; top right: photo by Ed Meyer, Globe-Democrat Collection, St. Louis Mercantile Library; bottom: photo by Paul Hodges, Globe-Democrat Collection, St. Louis Mercantile Library.

First published 2018

e-book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.43966.412.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017960107

print edition ISBN 978.1.62585.906.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

On December 2, 1963, Joseph Arbeiter walked into our house through the front door and murdered our mother, Nancy Zanone. Our family entered irreversibly into a selective fraternity that nobody seeks: surviving relative of a loved murder victim. It is an experience from which one never fully recovers, a scar that remains suppressed as a dull, lingering emptiness. You want revenge. You settle for justice. In our case, we got neither.

After the shock wore off, the adults in the family handled the aftermath of unexpected death the way people did in those days. Aunts, uncles and grandparents all seemed to retreat into their own silos of quiet grief, a sort of unspoken pact of mutual silence. They rarely spoke about her, especially to the children, as if the memory of her life and the pain invoked by the memory of her tragic death were inseparable. So, the adults smiled as much as they could and pretended everything was okayexcept it wasnt. For the children in the family, especially for my sister and me, this silence was both noticeable and confusing, and although no one specifically told us not to, we were reluctant to mention our mother. In our minds, we were somehow responsible for the adults emotional well-being, especially that of our dad, and we feared that speaking of her would only upset them. My sister and cousin sometimes secretly hid behind the bed in our cousins bedroom, quietly whispering memories of her to ensure they wouldnt be overheard.

The tangible impact for me was that, as a two-and-a-half-year old, I no longer had a mother. She was there one day, gone the next, and nobody fully explained to me why. With any conscious memory of her fading, until it disappeared, my mother became to me a mythical figure. Only still photos served as evidence she had existed, but a picture has no voice. Photographs are an inadequate surrogate for the real thing.

I also had little comprehension of what actually happened that day; just an allusion here and there. I knew who Joseph Arbeiter was and what he had done and that, somehow, hed gotten away with it. Why did he kill our mother? Why was he not in prison? What does justice look like? Why didnt we get it? I was naturally curious about the facts and longed for someone to tell me more, but I was afraid to ask. Where was I? What did I see? How aware was I that something had gone horribly wrong that day? I had to have seen something, felt something, but nobody would tell me. That left only a confusing array of seemingly disconnected facts and a blurred recollection of standing next to my sister watching out a window as a black-and-white vehicle, with its sirens blaring, carried our mother away. It never brought her back.

Two childhood dreams hinted at my experience, dreams Id kept guardedly to myself. In the first dream, I was looking up a long set of stairs surrounded by dark, wood-planked walls, covered by a shadowy roof. I could see my mother sitting at the top of the stairs with the door open, exposing a bright white kitchen above. Then, a faceless figure comes up from behind her with a knife. I can see him raise, then lower, his knife-wielding hand toward my mothers back. I woke in silent panic and heavy breath before the blow struck. In the second dream, I was in the same kitchen doorway, this time looking down those same dark, dreary stairs. My mother is lying at the bottom of the landing with her head propped up against the wall. I look down, feeling only puzzled. I woke up, and she was gone forever.

Life continues a persistent, measured pace forward. We take only brief glimpses back to the path from which we came. Our family was no different as we rebuilt our lives into something for which we can be thankful. Life returned to relative normalcy as years passed and then moved further in the rearview mirror. School, careers, birthdays, weddings and holidays came and went. The anger slowly slipped below the surface, barely detectable, and weve even been able to have a few conversations to learn a little bit about our mother. Bur the aftereffects have never completely subsided. Something is missing, and I have this nagging sense I will never find it. I live with a subtle, yet haunting, unease, trapped between the reality of what is and dreams of what could have beenif only the front door had been locked.

David Zanone

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our first words of thanks go to the Zanone family: David, Laura and Don. We recognize that all the questions, the probing, the opening of old wounds was difficult for you. We hope the end result is worth it, and we thank you for all your cooperation.

To Carrie Spencer Gruenenfelder and Julie Gruenenfelder, we thank you for your memories of your mother, Joan Gruenenfelder, and her work to change the juvenile system.

To Brendan Ryan, a thank-you for the wonderful stories of the circuit attorneys office, particularly of your encounter with Joseph Arbeiter. You should write your own book.

To Gary Hummert, thank you for sharing your personal encounters with Joseph Arbeiter in the course of performing your duties with the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department.

To Amanda Irle, for so patiently and pleasantly answering all our questions and helping us, especially with the technical aspects.

To Nick Fry at the Mercantile Library at the University of MissouriSt. Louis for his research help

To Jim Erwin, for being there, for legal expertise and for just being a great husband and dad.

To Sarah Erwin, for your patience, support and for being a wonderful wife.

INTRODUCTION

I remember the first time I heard about Nancy Zanone. We were planning my sisters wedding to David, and I asked about Davids mother. She was murdered, my sister said.

I was uncommonly silent for a few minutes. Who? What? How? I asked finally.

A kid stabbed her in their apartment. Dave and Laura were there, playing outside.

Is the guy who did it in prison?

He got off.

How?

I dont really know, some kind of technicality. They dont really talk about it.

This was the closest I had ever come to someone who had been murdered. People I knew didnt get murdered. I was a writer and, at the time, wrote mysteries for kids. I immediately began plotting in my head: A young child witnesses a murder; the perpetrator isnt caught or convicted. When the girl is a teenager, the perp shows up again, and she recognizes him. When bad things start happening, she immediately suspects the man who killed her mother. All this was fiction, and I carried it around for a while.

Next page