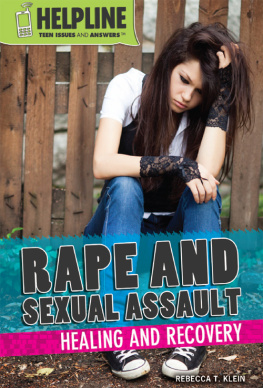

ONE HOUR IN PARIS

A True Story of Rape and Recovery

KARYN L. FREEDMAN

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

KARYN L. FREEDMAN lives in Toronto, Canada, where she is an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Guelph.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2014 by Karyn L. Freedman

All rights reserved. Published 2014.

Printed in the United States of America

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-07370-5 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-11760-7 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226117607.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Freedman, Karyn Lynne, 1968

One hour in Paris : a true story of rape and recovery / Karyn L. Freedman.

pages ; cm

ISBN 978-0-226-07370-5 (cloth : alkaline paper)ISBN 978-0-226-11760-7 (e-book)

1. Freedman, Karyn Lynne, 1968 2. Rape victimsBiography. 3. Women philosophersCanadaBiography. I. Title.

B995.F744A3 2014

362.883092dc23

[B]

2013027389

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Prologue

There are images in my head that do not belong there. No matter how hard I try to get rid of them they will not go away. It is as if they are permanently seared into my brain and written over my body. Over the years I have tried to talk them out, and when that didnt work, I talked louder. I have tried to write them out, paint them out, fight them out, and, by sheer determination, will them out. Occasionally, in darker moments, I have tried to drink them out. These efforts were not futile (except for the drinking). Each one helped in lessening the hold the images have over me, but none was entirely successful. They are mine for life, and that just might be the single most important fact that we can learn about psychological trauma. It is permanent. The psychological damage that results from uncontrollable, terrifying life events is profound. Not everyone who experiences a traumatic event becomes psychologically traumatized, but the ones who do are faced with enduring emotional, cognitive, and physiological consequences. This is true universally, even if the experience and aftermath of trauma varies historically and culturally. It has been over twenty years since I was raped, and I have finally reconciled myself to the immutability of trauma. I now understand that psychological trauma is not something from which one ever fully recovers. It is a chronic condition, and that means that the rape is forever my shadow. It tracks me everywhere. It follows me up the street to my local coffee shop in the middle of the day, and when I come home from a late night out with friends it is just over my shoulder. It is with me at work, in the classroom, and at play, in the dressing room before one of my recreational hockey games. Most especially, it stalks me in the bedroom. Twenty years later and I still have to work to put myself to sleep at nightand sleep is relatively easy, compared to sex. My body is interminably sensitive to the touch, the violence of the rape imprinted all over iton my breasts, my neck, my lower back, and everything important below that. For the most part I have not let this stop me from having sex, or enjoying it, for that matter, which I know to be a victory of sorts. But like most survivors of sexual violence I am anything but carefree with my body. I am never fully uninhibited when lying naked with another person, and I have had to set up strict boundariesno touching my head, no dark rooms, no spontaneous movesin order to protect myself from the images that will otherwise wash over me.

Having said that, the shadow of the rape is less conspicuous today than it once was. That is the result of a decade or so of hard work with an exceptional therapist, work which has shown me that a traumatic experience does not have to be a place of pain forever. With enough time and effort, survivors have a chance of moving through the memory of their experience and making it a place of transformation and emotional growth. My personal experience has taught me that to get out from under the hold of the memory of my rape I first had to live in it. Now, for the most part, I am able to remember the experience without being held hostage by it. Still, when I think about what happened to me in Paris, France, on the night of August 1, 1990, my left shoulder folds forward to protect my neck and my anus muscles shut tight. These bodily ticks are one sort of reminder of that night, and there are a host of others, too. These can make it a challenge to talk about my rape, or write about it for that matter, but nevertheless, I think it is important to do so. Some time ago I made a commitment to myself to tell my story, in part because I am persuaded by the notion that there are some phenomena, some of lifes events, that can be best accessed from the inside. I think that sexual violence is one of these. If I have learned anything from my experience as a rape survivor, then perhaps others can learn from my account of it. My hope is that through focusing intimately inward I am able to relate something that others can connect with.

I made the decision to write this book for another reason, too. It is close to fifty years since the beginning of the second wave of the womens movement in North America, which saw a number of seminal publications on the ubiquity of rape, and yet, despite impressive gains on a number of womens issues, sexual violence remains a dirty secret. Through statistics we may know of rapes pervasivenessone in three women worldwide, one every ten secondsthe social and cultural pressure on women to keep their stories private is, for many, an insurmountable hurdle. As a result, survivors of sexual violence remain anonymous, effectively closeted. This is deeply regrettable. It both reinforces the shame that we struggle against and widens the gap between who we are and how others see us. This also has the unfortunate consequence of making rape look like a personal problem, a random event that happened to me, for instance, because of where I was, what I was wearing, or who I was with, instead of what it really is: an epidemic faced by women and children worldwide which is the manifestation of age-old structural inequalities which persist between men and women. By speaking out about their experiences of sexual violence, survivors can help us to see the problem of rape as a problem of social justice. Thus, bodily tics notwithstanding, I have decided to tell the story of my rape. The story has some twists and turns, but it is a true story from start to finish, though I am likely guilty of some exaggeration and evasion, however inadvertent. For instance, as I remember it, the knife that was pressed into my neck (and other body parts) during the attack was ten inches long with a shallow serrated edge, but at least one reliable record of my experiencethe official transcript of the pretrial indictment, which contains my depositionsays nothing about whether the knifes edge was serrated. Now, it could be that the edge was serrated but that I failed to mention this fact in my testimony. Or it could be that because the knife felt sharp I drew the conclusion that it had a jagged edge. And I did not have a tape measure handy, so maybe the knife was eight inches long, or twelve. More to the point, I am certain that there are elements of my story that I do not remember, as paradoxical as that may sound. Our minds are powerfully protective of us and can block memories that we lack the emotional resources to handle.

Just over a decade ago, when I began in earnest to deal with the trauma of my rape, I discovered that my dad kept a file of every single correspondence and document related to it. I now call this my rape file, and it is over two inches thick. It includes the dozens of letters that I received over the years from various representatives of the judicial system in Paris (lawyers, prosecutors, magistrates and clerks), as well as each response that my dad sent back on my behalf from his law firm (both his handwritten drafts and the translations he had done by a bilingual colleague). It also contains medical documents, Visa receipts of airline tickets, and hotel bills from a couple of trips to Paris, a copy of the aforementioned transcript of the pretrial

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).