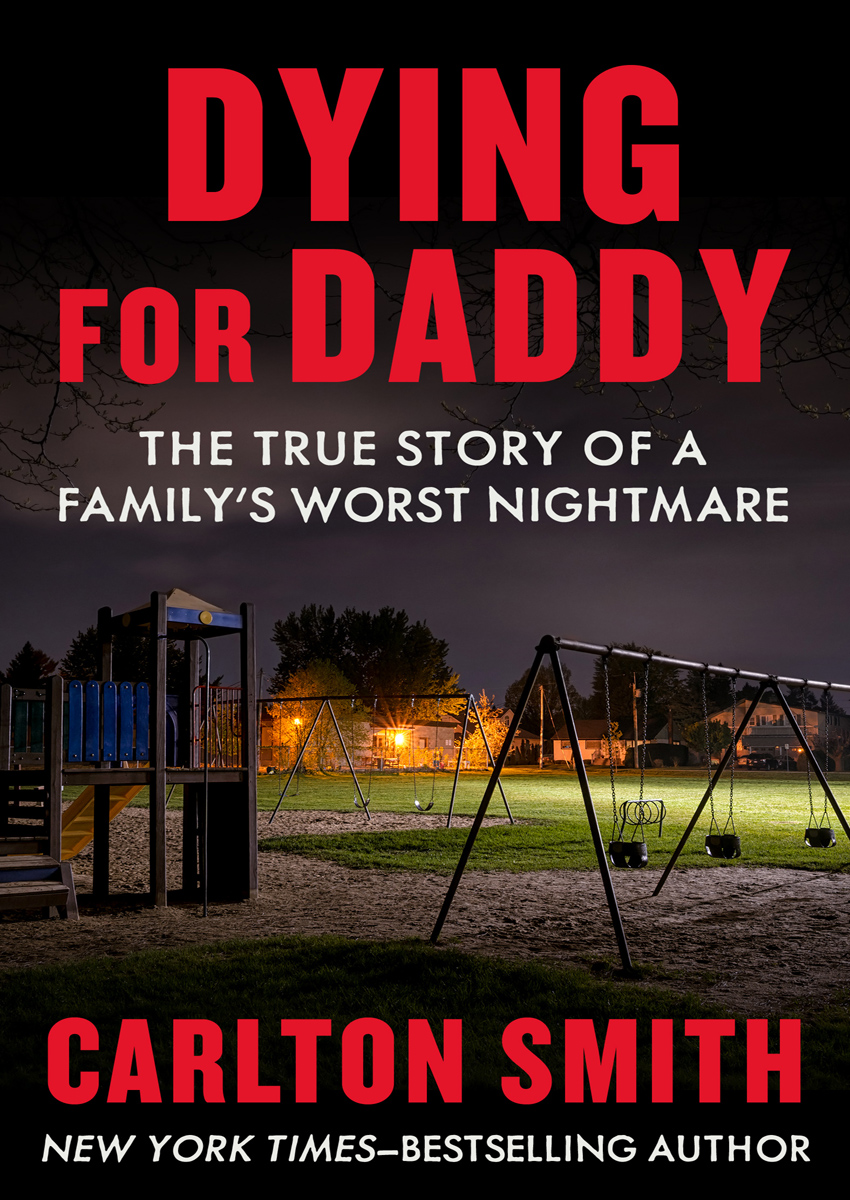

Dying for Daddy

The True Story of a Familys Worst Nightmare

Carlton Smith

I am really sorry youre unhappy right now. I have a hard time believing the only reason for this is my inability to keep the house exactly the way you like it. We usually have so much fun together. We have so much to be happy and thankful forIt really upsets me when I hear you talk about divorce Things have been so good for us for so long, you dont just wake up one day and suddenly decide something like that.

All my love,

Irene

from the Warrant for the Arrest of

Jack Kenneth Barron

BENICIA, CALIFORNIA

Monday, February 27, 1995

One

Punchout time came sooner than Jack expected, almost before he was ready. Hed risen before dawnwhat was it, 4:30 A.M. ?to drive to his new job on the trains. Even though he was sick, Jack wanted to show his new bosses they could depend on him.

For the first time in many years, Jack had all the reasons he needed to be happy. It was the new job. After years of shelving canned goods, paper products, and cereal boxes, of being a rarely noticed grunt worker in the anonymous aisles of supermarkets from Shasta to Sacramento, Jack finally had a real job, the one hed always wanted: he was a railroad man.

The thundering throb of the locomotives, loud enough to make the air vibrate and the ground shake with all the power they contained, had always thrilled Jack Barron. The sheer, frightening energy of the gigantic diesel engines, the whoosh of the air hoses, the squeal of the braking wheels on the hard steel of the tracks, coupled with the intense awareness that a single moments inattention could result in instant annihilation, all bespoke the awesome magic of the world of rails.

The world of trains had been important to Jack almost as long as he could remember. It had begun when he was small, when his father was an engineer for the Southern Pacific. Being able to control the enormous power of the locomotive, the complex switching mechanisms, the time and motion and distance of the elaborate network that tied a continent into a steel-solid wholethis was satisfaction the ordinary man might never enjoy. From the cab of a locomotive, the whistle said it all, even if the pay was only $13 an hour and change.

Not that Jack got to go very far, at least so far; he hadnt seen much of America yet. As a new hire for Amtraks Northern California operations, Jack was the low man on the signal-pole; although grandly titled Assistant Conductor, Jack spent most of his time helping two other men assemble the Amtrak trains at the Alameda, California, maintenance yardhooking up the airbrake hoses between the locomotives and the passenger cars, relaying hand signals between the conductor at the rear of the train and the engineer in front, and in general, helping to bring this newly composed train into the Oakland depot, where the operating crew would take over, after which the passengers to points north, south, and east would take their seats.

After that, for Jack and his co-workers, it was back to the maintenance yard to put another train away, and to get yet another train together for the journey into the heartland of America. Grunt work, it was.

But still, it was railroad work, just as hed yearned for, for almost 20 yearsever since the day in the early 1970s when his father, Elmore the railroad engineer, had walked out of Jacks life and had never come back, thereby leaving a 13-year-old boy to wonder what it was that he had to do to be a man.

Jack had wanted this railroad job so badly for so long that his mother Roberta, despite her bitterness toward Elmore, had prayed every night, rosary in hand, for Jack to get his wish, his chance on the Big Steel.

On this Monday, February 27, Jack spent his worktime with Frank Klatt, the conductor, and Phil Gosney, the engineer. Together the trio worked to retrieve locomotives from the roundhouse, connect them to the cleaned and serviced passenger cars, and run the assembled train into the Oakland station five minutes away.

Then, as usual, the three would wait for an incoming train, pick up that train when it arrived, and deliver it back to the yard, where the locomotive and the cars would be separated, the engine washed down, and the cars delivered for servicing. Jack spent much of the time with either Klatt at the rear of the train, with Gosney in the cab, or in between the two as Jack connected the cars or relayed hand signals from Klatt to Gosney, or from Gosney to Klatt. It was fairly intense work: a lot of running around, punctuated by intermittent periods of inactivity while the crew waited for another train to arrive or depart.

But just after 1:30 P.M. , the workday was over. Klatt and Gosney marched to the timeclock at the stationhouse and punched out promptly. So did Jack.

As he drove his van east on State Highway 24, through the Caldecott Tunnel burrowed under the Berkeley hills, through the suburb of Lafayette and down into Walnut Creek, Jack considered his relationship with his mother, Roberta. Theyd had a few troubles recentlypretty much what you might expect when a 34-year-old man moves back home to share space with his 52-year-old parent.

She still treats me like Im 13 or 14 sometimes, Jack thought. It was irritating.

But, Jack supposed, occasional flare-ups were only to be expected under the circumstances. Roberta Butler had never been known as any kind of shrinking violet when expressing her opinions. She had a tart tongue and was quick to use it. Still, he loved his mom, and he was sure she loved him. After all, shed stood by him, no matter how bad it had gotten over the past few years, even when people had said things that werent fair

While he drove, the wipers swished across the windscreen, spreading the drizzle. The wet weather wasnt making him feel any better, especially with his cold. It had been raining forever, it seemed. The storms had started just after Christmas, and the water came down unrelentingly throughout the month of January and much of February. It was, some said, the most rain the Bay Area had had in yearsand desperately needed after a long drought. Even so, with the reservoirs now filled to overflowing and some small towns inundated with flood waters, there were limits to too much of a good thing. It was all a matter of degree. Thats what everyone always said, that moderation in everything was the key. Thats what Roberta had always argued, even if she didnt always practice what she preached.

In Walnut Creek Jack merged onto Interstate 680 and headed north. In just a few minutes he passed Concord and was on his way into Martinez, where the gray waters of Suisun Bay soon came into view. As he crossed the Benicia Bridge across the east end of the Carquinez Strait, he could see the scores of empty gray ships tied up, bulkhead to bulkhead, masts and superstructures looking like some exotic, unreachable, technical city of the future, even though you knew they were just riding high and empty, useless, mothballed in the backwater. Then farther in the distance, just over the far hill, came the tops of the towers, tanks, and pipe lattices of the refineries behind Benicia, still more outsized technological artforms.

At the north end of the bridge Jack slowed down and passed through the toll booth, handing over the toll coupon and getting a receipt that was time-stamped in return. As soon as he was through the tollgate, Jack swung west onto Interstate 780, and the last mile. At the West Seventh off-ramp Jack exited once again, and drove under the freeway into the Southampton residential development. From there it was a short distance to homeactually, Robertas home, a modest green, woodsided condominium that overlooked the freeway.