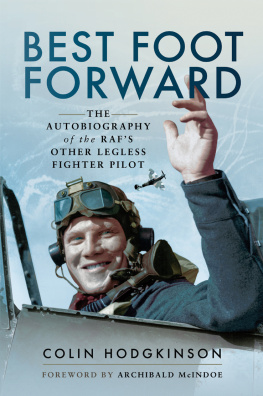

BEST FOOT FORWARD

BEST FOOT FORWARD

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY of the RAFS OTHER LEGLESS FIGHTER PILOT

COLIN HODGKINSON

FOREWORD BY ARCHIBALD MCINDOE

Frontline Books

BEST FOOT FORWARD

The Autobiography of the RAFs Other Legless Fighter Pilot

This edition published in 2017 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

First published by Odhams Press Limited, London, 1957.

Copyright Colin Hodgkinson, 1957

The right of Colin Hodgkinson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-47389-762-5

eISBN: 978-1-47389-764-9

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-47389-763-2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please visit

www.frontline-books.com

email

or write to us at the above address.

Contents

Foreword

By Sir Archibald McIndoe

In 1939 Colin Hodgkinson was 6 feet 1 inch tall and weighed 13 stone of solid and well-trained bone and muscle. He had so far enjoyed a magnificently physical life of games, shooting, hunting and boxing, interspersed with some education. In that year, too, he was under training as a pilot in the Fleet Air Arm. In 1940, following a near fatal air crash, he was 5 feet 10 inches tall, and, minus two legs, weighed 12 stone. He was on the beach, having been invalided from the Navy with a pension of 3 per week. During his short service life he had often speculated far into the night with his fellow pilots on the possibilities of sudden death or survival in the war which was certain to come. Whatever they thought of war as a means of settling international difficulties, they were agreed that they had to take their chances. It was death or glory. None of them ever considered the likelihood of permanent disablement, for young men believe that such things always happen to someone else.

I met Colin first at Dutton Homestall during the fateful days of September, 1940. He was a red-headed thick-set figure precariously balanced on two artificial legs, which were planted firmly apart and braced backwards to support his swaying body. His face was badly scarred. His eyes reflected a bitter desperation mixed with wariness which betrayed a constant anxiety to maintain his balance. He kept within reach of a wall or a convenient chair. He was watching me carefully and obviously had something to ask me. We moved into a corner and talked. He wanted to know whether I could get him back into the Air Arm as a pilot.

Hodgkinson was one of the wars earliest victims of the ninety-day rule. By this, from time immemorial, an injured service man was given three months to return to duty. If, at the end of that time, he was still unfit, he was invalided as useless and passed to one or other of the various Civil or Pensions hospitals for further treatment. After this he was pensioned for as small amount as could be determined from the schedule of payments authorized for his particular disabilities. If the convalescence was a long one this system absolutely guaranteed that the man would arrive back in civilian life without hope, broken in spirit, bitter and disillusioned. He could also be in debt for, with invaliding, his service pay ceased and the eventual pension would not be settled for a long time. During this period he lived on charity.

Colins problem interested me because I had, at that time, under my care a large number of men who could possibly suffer the same fate. This one was sufficiently arguable to blaze a trail for the rest. The first thing to be done was to make him one of mine by operating on him. This created a certain bond between my patients and myself. Thereafter we moved together.

There are times in life when an approach through the usual channels is sufficient to drive a way through rules and regulations. Here it was impossible, for no Civil Servant would dare to break Kings Regulations. These would have to be altered before this problem could really be solved. Creating a precedent with a cast-iron case at a very high level seemed to me the best approach.

Three months later Colin was back in the F.A.A. He was probably the first man ever to return to service drawing a pension for the very injury which had caused his invaliding.

His mood of bitterness did not last long. He knew that the road was now clear and he had opened it for others to bring about an alteration in Kings Regulations. One by one he satisfied his ambitions, first to fly, then to fly his beloved Spitfires, then to have what he still calls a bash. This bash was necessarily directed against Germany. But it did not mean entirely that. It meant proving that he was capable of achieving without legs exactly what his contemporaries could achieve with them. By the conquest of his own disability, he turned defeat into victory. How magnificently he has succeeded is described in a deadly honest and absorbing account of his life appropriately called Best Foot Forward . He pulls no punches and spares neither himself nor his enemies. He asks no quarter nor does he give it. He whacks his way to the front row with gusto and there he stands today. He no longer balances himself carefully and warily on his tin legs but stands sturdily upright, sure of himself.

Whenever I see him stumping towards me with that stiff outward throw of the legs from the hips and the slight forward lean of the body, his eyes looking eagerly ahead and a grin on his face, my heart gives a quick warm jump. This man has made his world and it belongs to him. How he did it will prove an inspiration to those who read his story. It is a great story.

Introduction

If you talk to surviving aircrew from the Second World War, many will not accept that they were brave men, invariably remarking that they were only doing their job. However, theirs was no ordinary job; their workplace was the sky, their tools were guns and bombs, their competitors a skilful and determined enemy.

Even learning their trade could prove fatal, as the numbers who died during training starkly reveal dangers that Colin Hodgkinson would experience first-hand. In Bomber Command alone, for example, between 1939 and 1945 there were 8,305 aircrew killed in training flights or on non-operational flying duties.

Just getting to grips with flying, in the unnatural environment of the sky in a cramped and sometimes unreliable machine, required an unusual degree of courage. Having mastered the skills, and overcome the fears of flying, the men would then be despatched to face flak, fighters and the ever-present risk of mechanical failure. Theirs, indeed, was no ordinary job.

For a fully-fit, strong and intelligent young man, flying and fighting in the air in the Second World War was an immense physical and mental challenge. But a few remarkable individuals battled not just the environment and the enemy, but also disability.

Next page