Contents

WHEN CLOUDS FELL FROM THE SKY

A DISAPPEARANCE, A DAUGHTERS SEARCH

AND CAMBODIAS FIRST WAR CRIMINAL

ROBERT CARMICHAEL

FOR NEARY

who trusted me with her story

And everyone wants to know: Who? Why? Out of the sighing arises more than the need for facts or the longing to get closure on someones life. The victims ask the hardest of all the questions: how is it possible that the person I loved so much lit no spark of humanity in you?

Antjie Krog, Country of My Skull

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friends or of thine own were; any mans death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

John Donne, Meditation XVII (1624)

MAP OF PRESENT-DAY CAMBODIA

This map, using the countrys 2015 provincial boundaries, illustrates the locations of all places referred to in the book.

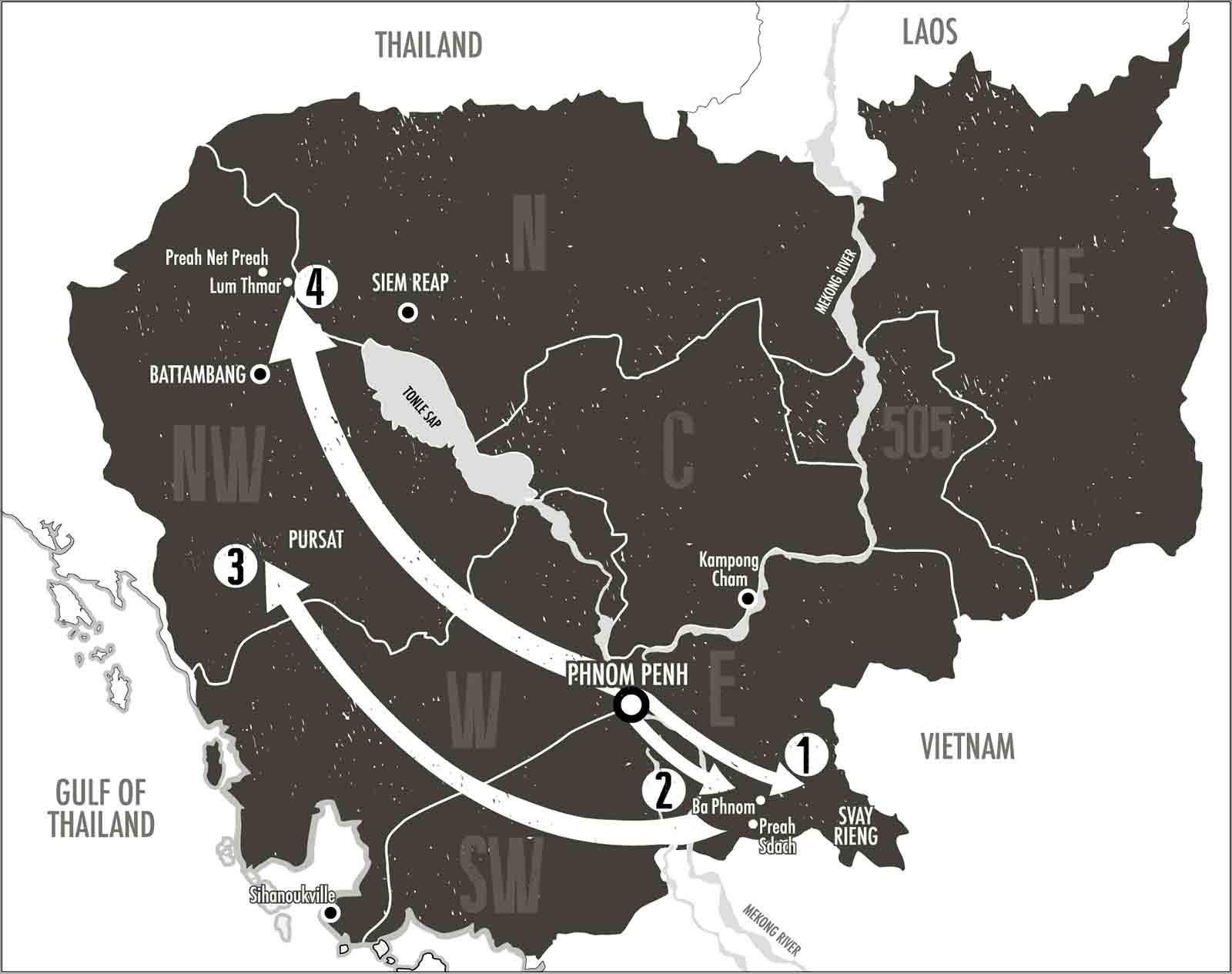

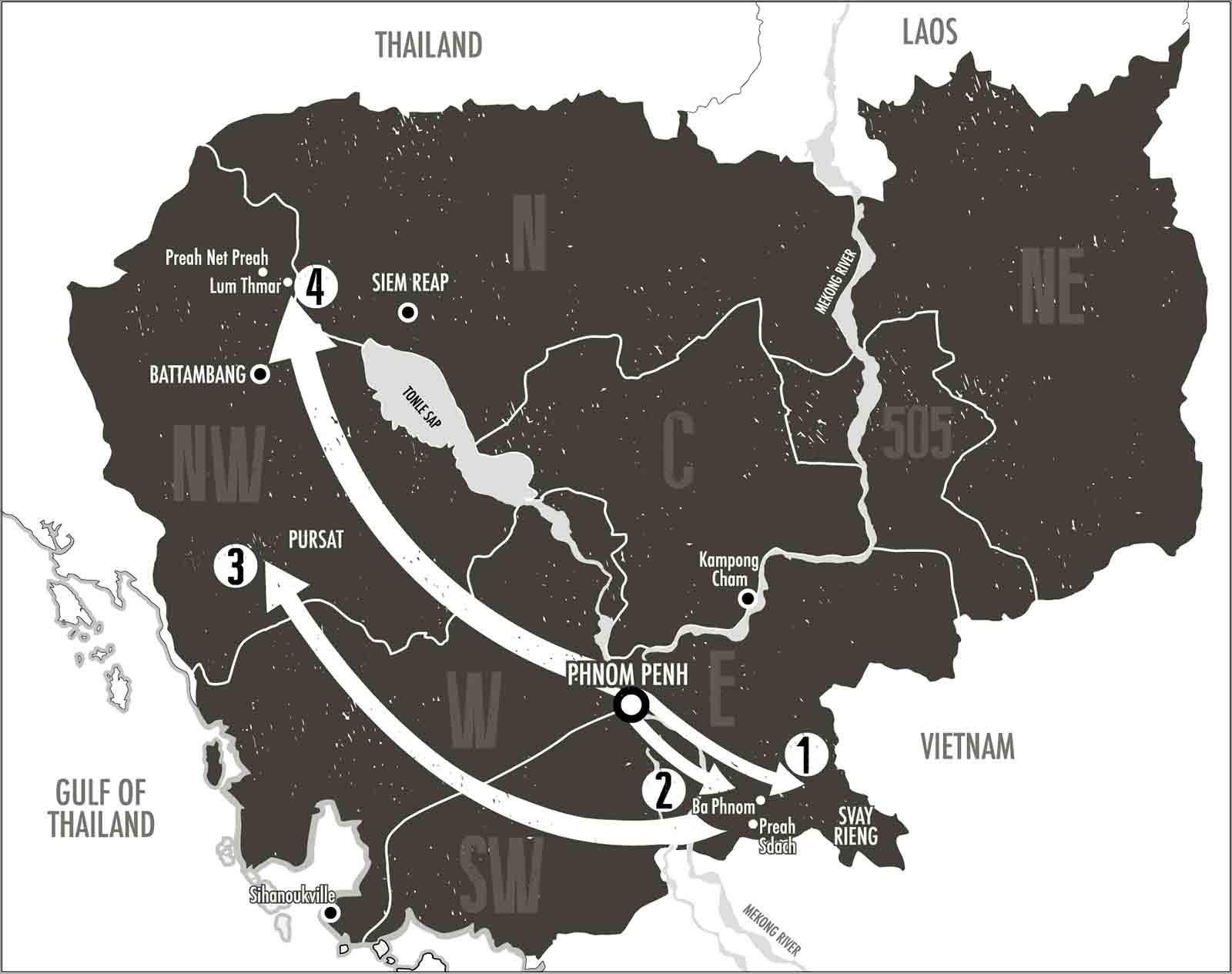

ZONE MAP OF DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA (1975-79)

Under the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia was renamed Democratic Kampuchea and divided into geographical zones. Among those was the North-west Zone, which is where most of Ouk Kets family was sent in 1975. The maps arrows show the paths taken by Ouk Kets relatives.

1. Journey of Ouk Saron, Kets brother, to Svay Rieng in 1975.

2. Journey of Sam Sady, Kets cousin, and her family in 1975, first to Ba Phnom and from there to Preah Sdach.

3. Journey of Sam Sady and her family to Pursat in 1977.

4. Journey of the members of Kets family - his parents and most of his siblings - to Lum Thmar in 1975.

PREFACE

CAMBODIA HAS TAKEN UP far more of my life than I dreamed it would. When I first arrived in 2001, I expected to spend a year, perhaps two, working in Phnom Penh as a journalist. As it turned out, I did leave after two years but I returned in early 2009 to cover the trial of Comrade Duch, the former head of the Khmer Rouges brutal torture and execution centre codenamed S-21, and one of the people at the heart of this book. At the time of writing I have lived here eight years.

My fascination with the country stems in part from my keen interest in how humans survive the most punishing experiences from the First World War to the Holocaust to the siege of Stalingrad. Although I dont recall when I became aware of humankinds remarkable capacity to endure, it might well have had something to do with the fact that my grandfather survived months in the trenches of France and Belgium during the First World War.

My linked interest in the injustices that humans feel permitted to inflict on others was surely the product of growing up in South Africa: I was at school in the 1980s as apartheid was driven to collapse, and I was struck by what was taking place outside the privileged suburbs of my youth.

It goes almost without saying that there are numerous and profound differences between South Africa and Cambodia, yet one element they have in common is a post-atrocity reckoning of sorts for the suffering meted out to the majority of their peoples. South Africas effort, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), began its hearings in 1996. This was explicitly not a judicial process; its mission was to promote healing and understanding. Perpetrators who told the truth about their acts of political criminality were effectively guaranteed an amnesty. Although I was living in London during the two-year-long TRC process, I made sure to attend hearings on my rare trips back to Cape Town.

A decade later the tribunal to judge the crimes of the Khmer Rouge, the communist rulers of Cambodia between 1975-79, started its work. The model chosen was a hybrid court, part United Nations, part Cambodian, whose mixed nature is reflected in its unwieldy name: the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). It is more commonly known as the Khmer Rouge tribunal. Its mission was to judge the surviving senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge as well as those thought most responsible for the crimes of the period a huge task given that two million people, or one in four Cambodians, are believed to have died from execution, starvation, illness or overwork in less than four years.

I felt then about the TRC as I do now about the Khmer Rouge tribunal: that witnessing such events is a rare privilege. I am extraordinarily fortunate to have been able to follow Cambodias experience at such close quarters.

The topic of post-atrocity justice is both complex and fascinating, and the different paths chosen by South Africa and Cambodia are instructive. Neither is perfect, and nor could they be given that they are dealing with crimes against humanity, yet they went their different ways on the logical ground that doing something is surely better than doing nothing.

Rights advocates disagree with a TRC process that offers immunity in exchange for the truth. Critics of the court model, on the other hand, say it is slow, costly and particularly when held outside the country where the crimes took place of limited value for those whom it is meant to represent. A judicial process focuses less on truth, more on evidence and procedure, and is little concerned with reconciliation. Who is to say which of these truth, justice or reconciliation is the most important?

And yet, while the ECCCs hybrid model had the benefit of conducting its hearings inside Cambodia and in Khmer, the local language, its major flaw was that locating it in-country left it open to political interference. Such meddling is, perhaps, no surprise; after all, these are formal mechanisms to deal with crimes that are inherently political. What counts is who takes the decision on how to proceed.

In South Africa, the African National Congress won the democratic vote in 1994, ousting the apartheid-era National Party. In Rwanda, where 800,000 people were murdered in three months that year, Paul Kagames Rwandan Patriotic Front expelled its genocidal predecessor. In both cases the incumbents lost power; the winners, untainted by the crimes of the previous regime, chose the path (though the TRC was not without its compromises).

Cambodia was different: its current government was installed by Hanoi in 1979, and many of those in power today, including the three men still (as of 2015) at the top of the ruling Cambodian Peoples Party (CPP), were Khmer Rouge officials who defected prior to the January 1979 overthrow of Pol Pots Democratic Kampuchea. That meant this new government was no out with the old but something much more subtle, and the choice of a tribunal rather than a TRC was a direct consequence; the opaque balance of political power meant Prime Minister Hun Sen had little to gain from a TRC process. On the other hand a multi-million dollar hybrid court where Cambodian judges were in the majority, despite the checks and balances designed by the United Nations to stop political interference, was more appealing.

The scale of Cambodias experience also precluded a fair solution. With the best will in the world, no country could tackle the criminal neglect and cruel actions that led to the deaths of so many men, women and children, a near four-year period of catastrophe that many Cambodians refer to as