INTRODUCTION

He leads us still. Oer chasms yet unspanned

Our pathway lies; the work is but begun

Arthur Guiterman

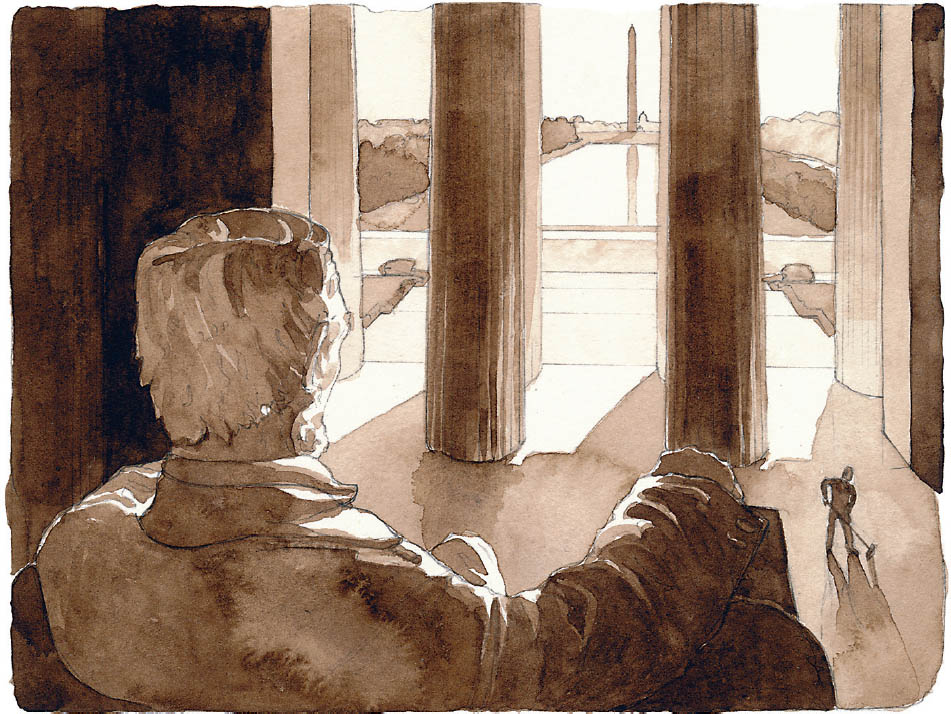

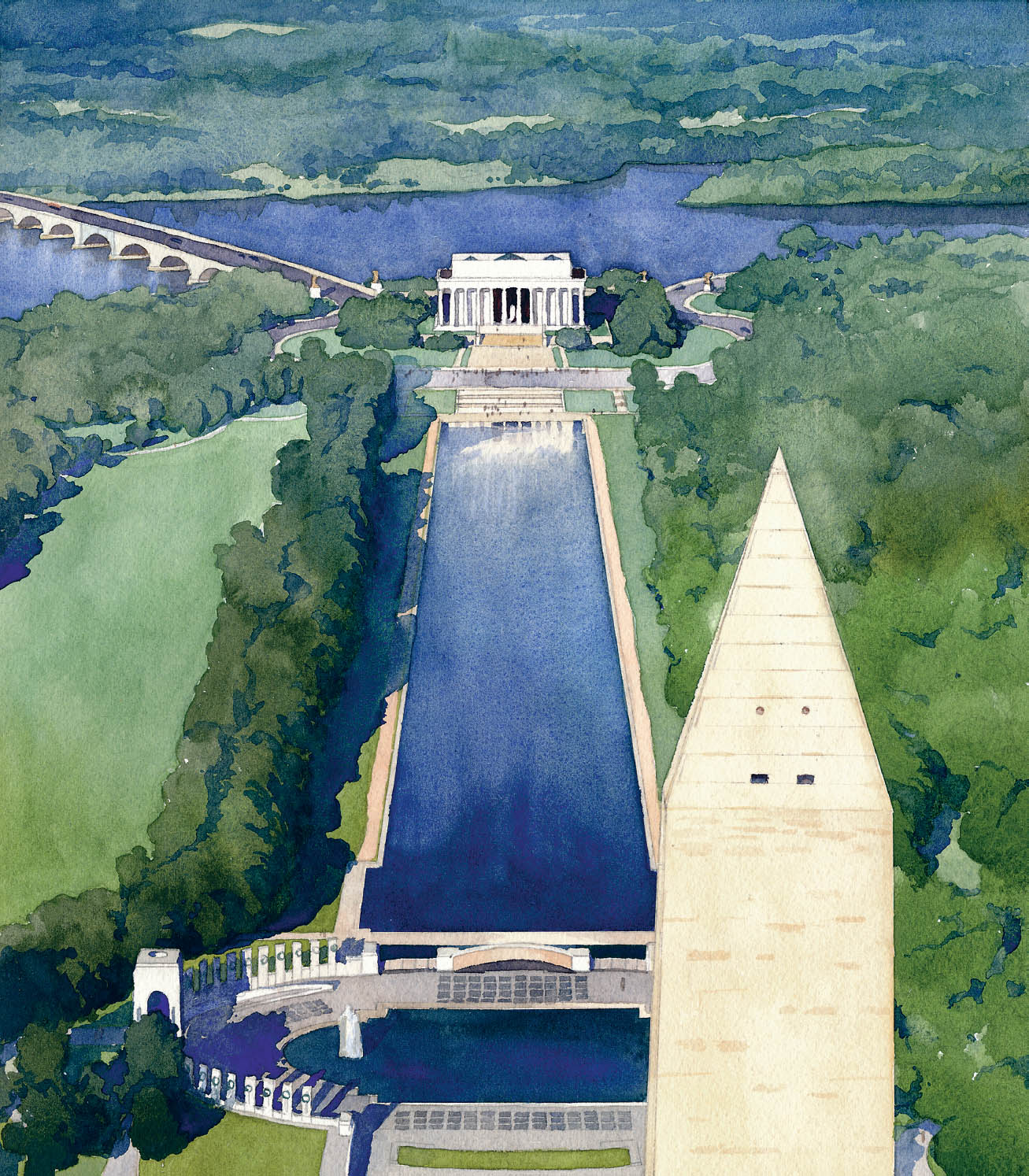

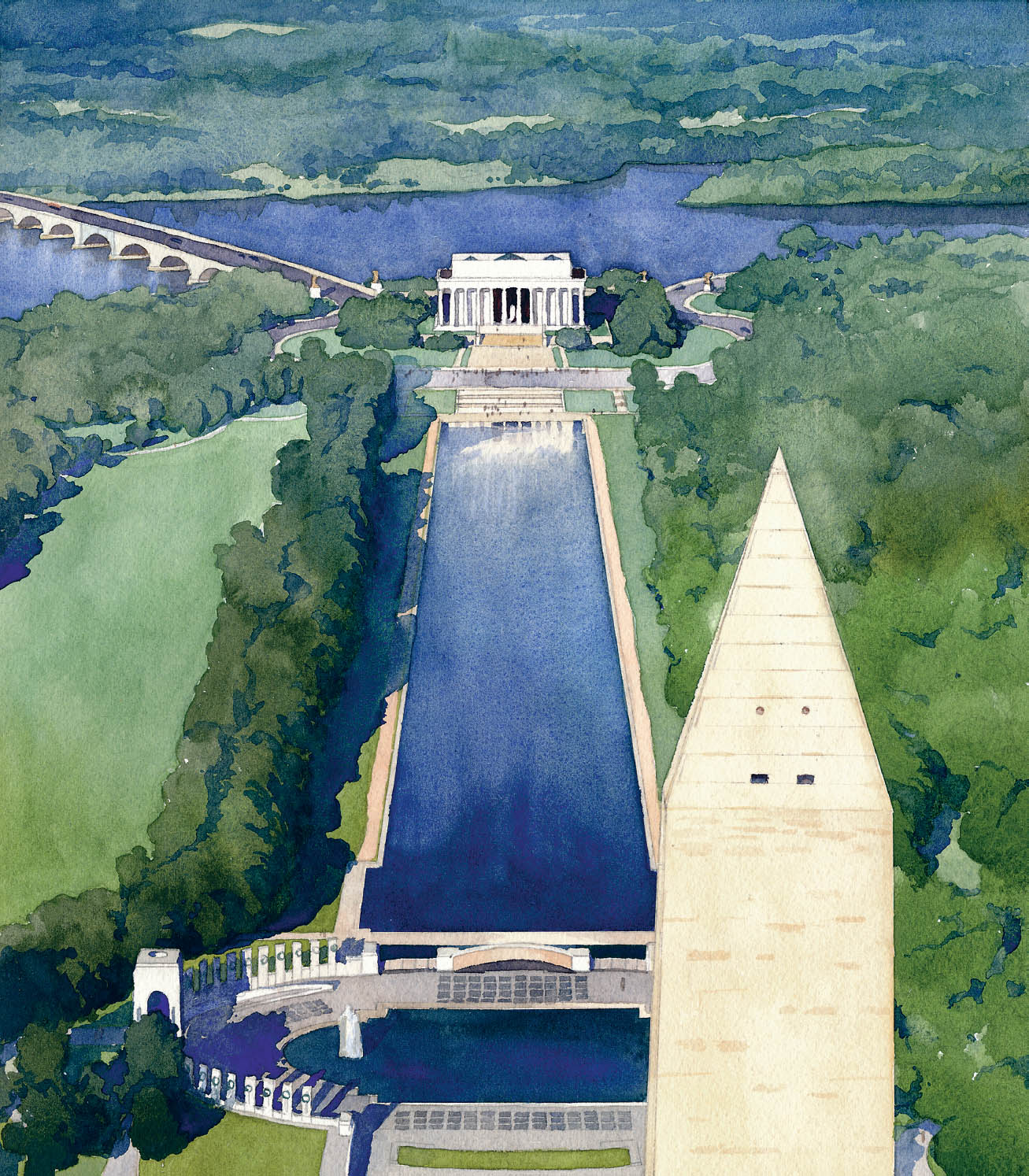

T he Lincoln Memorial sits along the banks of the Potomac River at the western edge of the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Its impressive to behold; built of gleaming Rocky Mountain Yule marble, it stands almost a hundred feet high, its massive columns echoing the stately provenance of the temples of classical antiquity. The seated statue of Lincoln, nineteen feet tall, gazes soberly out toward the Mall, past the shimmering Reflecting Pool, over the Washington Monument, and onward toward Capitol Hill. But then, you probably know this already. Its rare to meet someone who cant instantly recall an image of the Lincoln Memorial.

That its an international icon there is no doubt, and that its an elegant and austere feat of architecture in a historic swath of public space is readily evident. What is truly remarkable, however, is that it is perpetually effective. How often does the familiar remain powerful? How often do planned public spaces maintain a relevance to the moment or the figure that they commemorate? History has a way of softening the intended meaning of a space. Even successful monuments, like many of the others on the very same stretch of the Mall as the Lincoln Memorial, can easily become nothing more than a destinationa pretty bit of marble work and a noble use of public funds, but little more than a place to buy a picture postcard.

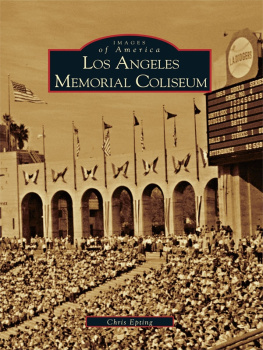

The Lincoln Memorial from the Washington Monument

How then, does the Lincoln Memorial succeed in staying relevant on both a political and an emotional level? By all rights, it shouldnt. Its image is stamped onto the back of pennies and printed on the back of the $5 bill. Its almost as familiar an icon for America as the bald eagle or Uncle Sam. The cartoon visage of Lincoln is used, along with his cherry-tree-chopping colleague, to sell cars and televisions every year on the third Monday in February. And yet, despite its utter ubiquity, the power of the Lincoln Memorial remains as real and solid as the marble it is constructed from.

The riddle of the memorial is akin to the riddle of its subjects life and legacy. Abraham Lincoln was a plain-spoken, intelligent, and forceful man, born at the right time in history, who, through the strength of his will and acuity of his political gamesmanship, and through the bloody veil of years of war, forced a country to accept an idea that it was incapable of accepting on its own. Lincolns legacy remains a hinge point in American historybefore Lincoln and the Emancipation, and after. And the memorial, while intended to revel in historical significance of the great man and his moment, ushers forth as its own hinge in historyinstead of looking back, it always looks forward. It begs those who visit it to consider both the courage and the sins that it is built upon. The Lincoln Memorial is where America gathers to challenge itself.

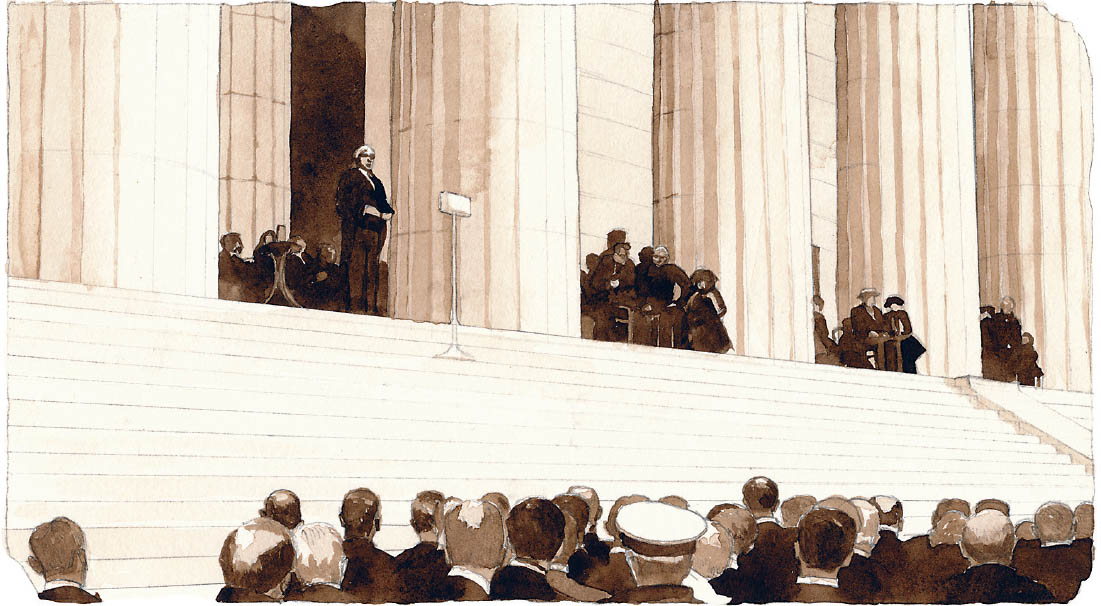

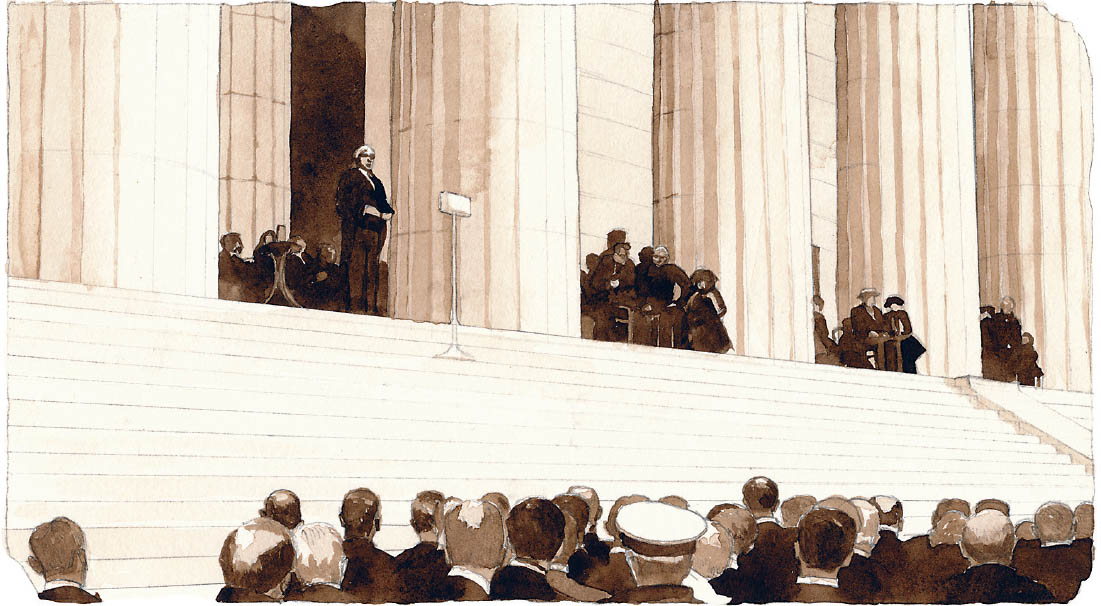

And it has always been so. Its promise is present in the contradictions it showcases. At its dedication ceremony on May 30, 1922, President Warren G. Harding gave a reverential, if somewhat restrained, speech about Lincoln and his accomplishments. Harding posited Lincolns great struggle as being first and foremost for the preservation of the union. He spoke of an embattled president and a deeply moral man who feared the dissolution of the nation above a desire to see slavery abolished. Harding noted that Lincoln, hating human slavery as he did, believed that its abolition was inevitable due to the developing conscience of the American people. It wasnt that Harding wanted to gloss over the abolishment of slavery as a major accomplishment as much as he and the trustees of the memorial hoped to gently control the symbolism of their new temple. They wanted Lincoln and the memorial placed firmly into history, a static reminder of a great man. The problem is that the very narrative of the memorials subject is a man who refused to let the machinations of history impede him from his mission. Faced with the imminent collapse of the Union, and aware of the innocent blood that would be spilled in the effort to both destroy the institution of slavery and save the United States of America, Lincoln had no choice but to give history a push.

And the power of the memorial resides in its ceaseless reminder to us that history still requires pushing. Even on the day of its dedication, as President Harding spoke to a crowd of fifty thousand people about the evil and greed inherent in the idea of human chattels, the African American onlookers were obliged to stand apart from the rest of the crowd, separated from their fellow citizens by a dirt road and a rope-lined barrier. Dr. Robert Russa Moton, one of the speakers that day, remained behind that rope barrier until he was called up to the steps of the memorial by his white colleagues.

It seems unimaginable today that a monument that has become shorthand for equality and justice, and that was built with the good will of many enlightened individuals, would still be hampered by the prejudices of its time. And yet again, it is only with slow and steady urging that the monument, and the courageous people who have rallied to it, have been able to bend the worlds ear to the march of equality. In 1939, some seventeen years after Dr. Moton was snubbed, the memorial again played host to a massive crowd of onlookers. This crowd, however, was racially integrated. They gathered on the mall to hear the African American opera contralto Marian Anderson perform a selection of arias and popular songs. Earlier that year, Anderson had been barred from performing at Washingtons Constitution Hall after the venues owners, the Daughters of the American Revolution, refused to allow a black performer on their stage.

President Harding speaking at the dedication of the memorial