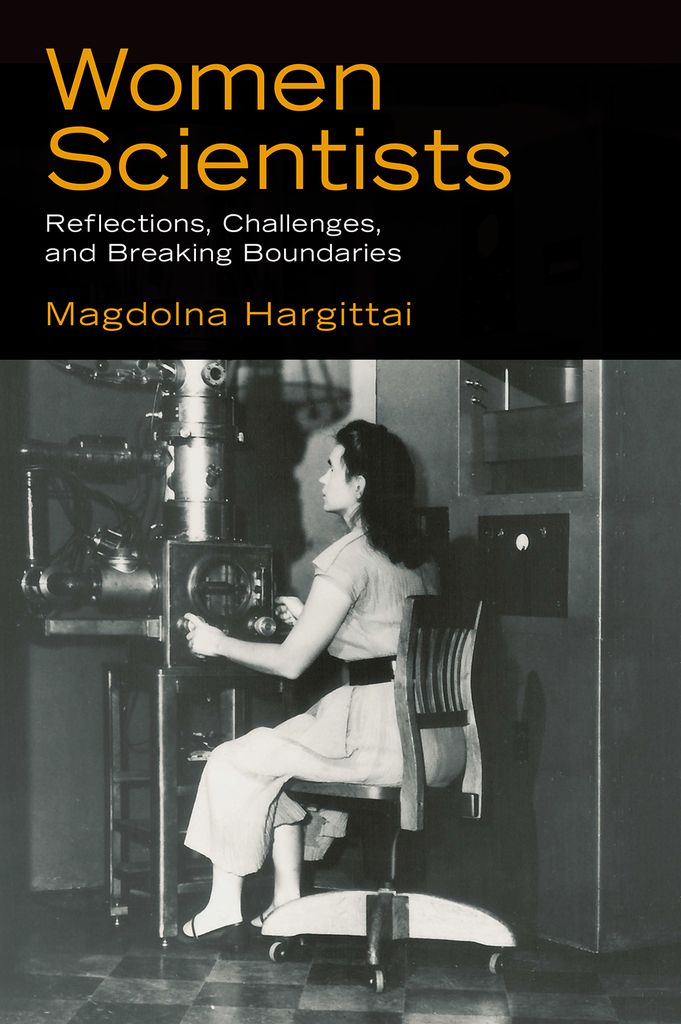

Women Scientists

Also by the Author

Great Minds: Reflections of 111 Top Scientists (Oxford University Press, 2014, with B. Hargittai and I. Hargittai)

Symmetry through the Eyes of a Chemist 3rd edition (Springer, 2009, with I. Hargittai)

Visual Symmetry (World Scientific, 2009, with I. Hargittai)

Candid Science IV, VI: Conversations with Famous Scientists (Imperial College Press, 2004, 2006, with I. Hargittai)

In Our Own Image: Personal Symmetry in Discovery (Plenum/Kluwer, 2000; Springer, 2012; with I. Hargittai)

Symmetry: A Unifying Concept (Shelter Publications, 1994, with I. Hargittai)

Cooking the Hungarian Way, 2nd edition (Lerner, 2002)

The Molecular Geometry of Coordination Compounds in the Vapor Phase (Elsevier, 1977, with I. Hargittai)

Edited Volumes

Candid Science I, II, III: Conversations with Famous Scientists (Imperial College Press, 20002003, with I. Hargittai)

Advances in Molecular Structure Research, Vols. 16 (JAI Press, 19952000, with I. Hargittai)

Stereochemical Applications of Gas-Phase Electron Diffraction, Parts A and B (VCH, 1988, with I. Hargittai)

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Oxford University Press 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hargittai, Magdolna, author.

Women scientists : reflections, challenges, and breaking boundaries / Magdolna Hargittai.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780199359981

eISBN 9780199360000

1. Women scientistsInterviews. 2. ScientistsInterviews. I. Title.

Q130.H376 2015

509.252dc23

2014028839

To the memory of my mother, Magdolna Reven Vmhidy;

circumstances prevented her from getting the higher education that she strived for.

CONTENTS

This book grew out of my encounters with famous womenphysicists, chemists, biomedical researchers, and other scientistsduring the past fifteen years. They are from eighteen countries on four continents. For a number of years, we had a family project of recording and publishing conversations with famous scientists, and we collected most of them in our six-volume Candid Science book series. Each volume contained at least thirty-six conversations, and at least half of them were with Nobel laureates. There were too few women in this collection, although we had no bias in selecting our interviewees. This led me to the realization of what others had noticed long before me: the unjustifiable underrepresentation of women at the higher levels of academia. When I was a student, majoring in chemistry, there were about the same number of women and men in our class. Then, moving up the academic ladder, the balance kept changing in favor of men. I myself could have fallen off this ladder at two important stages of my career, but luckily, I did not.

My future husband, Istvan, and I started seeing each other when he was a beginning researcher in a laboratory of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest and I was a sophomore in my university studies. We got married just before my senior year. His enthusiasm for his project was contagious, and I joined him for my diploma work (masters degree equivalent) and continued after my graduation. He was an independent researcher who had initiated his own project and needed associates. When he showed success, it generated appreciation as well as jealousy among his colleagues in the laboratory.

One daythis happened in the early 1970s in pro-Soviet Hungarythe so-called quadrangle of the laboratory, the director, the party secretary, the chief of personnel, and the trade union secretary, invited Istvan for a talk. They told him that it was not right for a husband and wife to work together. They were not belligerent and told him candidly that had he been less successful in his project, it would have not generated such interest in his circumstances. Istvan calmly responded that he understood and would start looking for a new job for himself. He later told me that his quick response surprised not only the others, but himself as well, because he knew that he could not have found another place with the level of independence and support for his ideas that his current position offered. Looking for a position outside of Hungary was unthinkable in those days; the borders were closed. Of course, the members of the quadrangle had taken it for granted that the wifethat is, Iwould be the one to go, as indeed would have been logical to expect. After this exchange, they never brought up the issue again, and since there was no official rule excluding husband and wife working together, we kept doing so for quite a few years.

This arrangement gave me a tremendous advantage when our children were born. I stayed at home for about six months each time, but was not left behind in my work, because we never separated our activities at home and the laboratory.

Before a too idealistic picture emerges from my account, I must admit that our family developed in a traditional way in that Istvans career was our focus. I found it natural that running the family was my duty, even though he helped in every way. However, the expression helped already gives the situation away; we were not equals in our duties at home. While our children were small, I put my career on the back burner; I did not want our son and daughter to suffer for having a scientist mother. I was slower in earning my higher scientific degrees than might have been the case had I not focused so much on raising our children, and my career took off around the time when our younger child entered high school. This was when I embarked on developing my independent research direction.

I had not wondered about the difficulties women scientists have to overcome until we were already well into our hobby, the Candid Science project. Eventually, though, I started wondering why there were hardly any women professors among my teachers, why I never encountered a woman dean let alone rector or president during my studies, and why there were so few female Nobel laureates. Once I made these observations, I decided to look for patterns and the roots of the problem. I sought out prominent women scientists with whom I could discuss these issues in addition to learning about their science. I started giving talks about women scientists, and the interest these talks generated encouraged me to continue these activities and led to the idea of this book.