Copyright Kate Armstrong, 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purpose of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

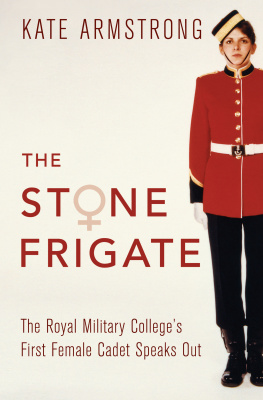

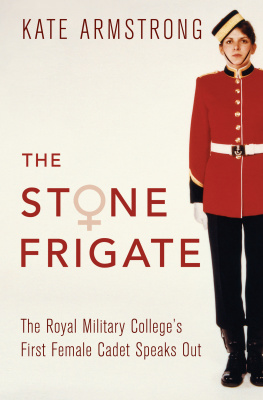

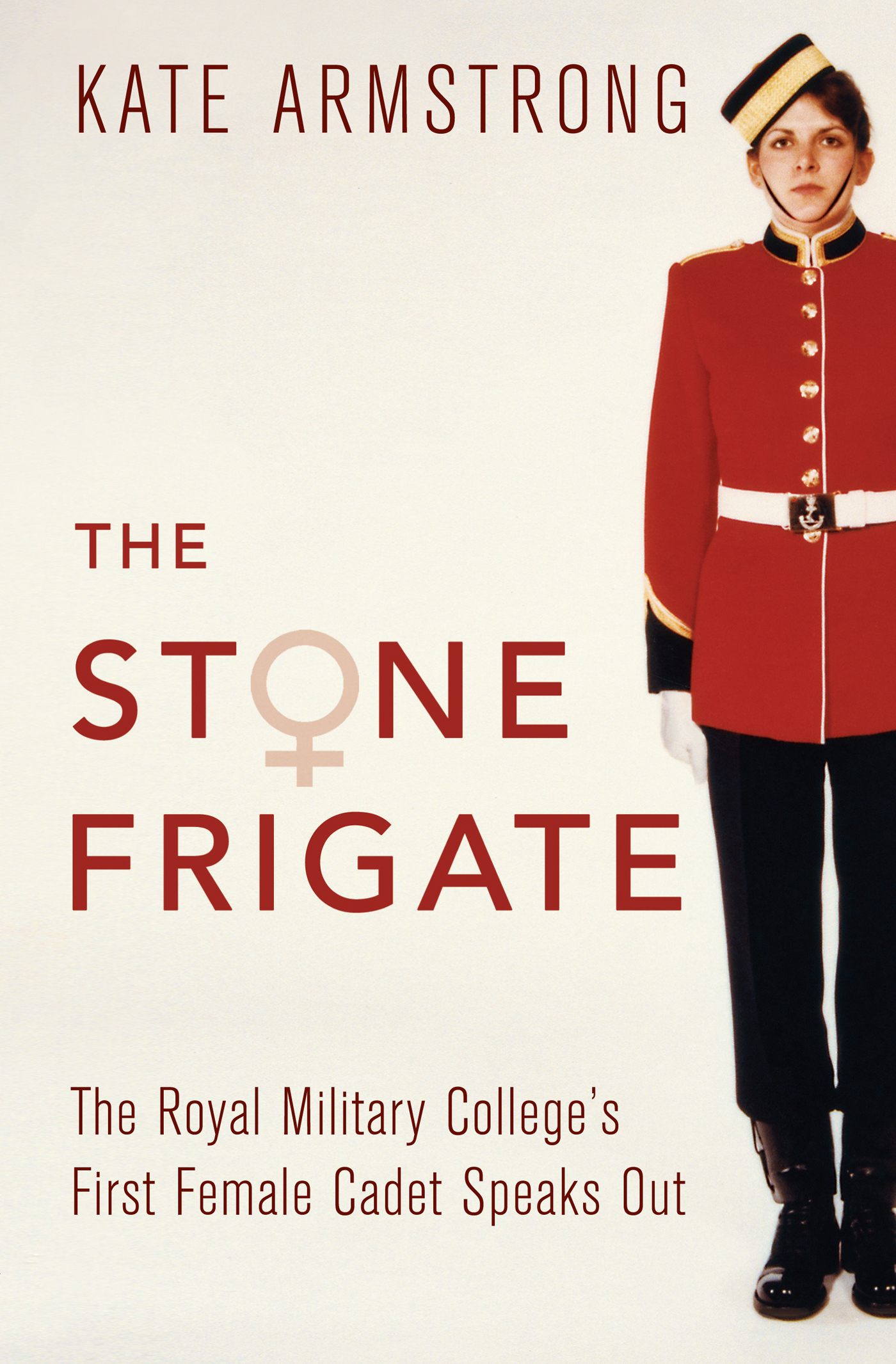

Cover image: RMC Archives

Printer: Webcom, a division of Marquis Book Printing Inc.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Armstrong, Kate, 1962-, author

The stone frigate : the Royal Military Colleges first female cadet speaks out / Kate Armstrong.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4597-4405-9 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-4597-4406-6 (PDF).--ISBN 978-1-4597-4407-3 (EPUB)

1. Armstrong, Kate, 1962-. 2. Royal Military College of Canada. 3. Women military cadets--Canada--Biography. 4. Women soldiers--Canada--Biography. 5. Women and the military--Canada. 6. Discrimination in the military--Canada. 7. Sexism in higher education--Canada. 8. Sex discrimination in higher education--Canada. I. Title.

| U444.K5R1 2019 | 355.0071171372 | C2018-906506-0 |

| C2018-906507-9 |

1 2 3 4 5 23 22 21 20 19

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country, and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Ontario, through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and Ontario Creates, and the Government of Canada.

Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien. Lan dernier, le Conseil a investi 153 millions de dollars pour mettre de lart dans la vie des Canadiennes et des Canadiens de tout le pays.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

The publisher is not responsible for websites or their content unless they are owned by the publisher.

Printed and bound in Canada.

VISIT US AT

dundurn.com

dundurn.com

@dundurnpress

@dundurnpress

dundurnpress

dundurnpress

dundurnpress

dundurnpress

Dundurn

3 Church Street, Suite 500

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5E 1M2

For the First Thirty-Two Women

CONTENTS

Great bodies of people are never responsible for what they do.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of Ones Own

PREFACE

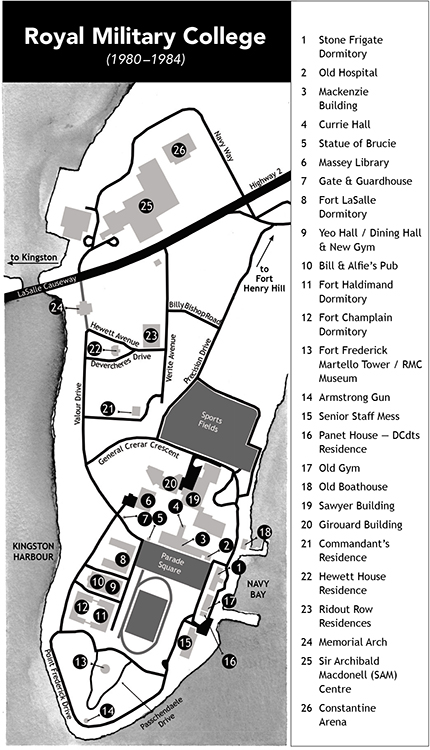

A question I have been asked frequently during my adult life is why I ever wanted to go to the Royal Military College, or RMC. My answer has been correct to a point: I wanted to be an air force pilot and to pay my own way through university. But, of course, it was more complicated than that. The real answer is that I didnt actually set out to go there at all.

At sixteen years old, in 1978, I earned my glider pilot licence through the Royal Canadian Air Cadets, and from the moment my wings were pinned onto my uniform, I knew I wanted to become a professional military pilot. I had no idea that women werent eligible to be pilots yet. In fact, I had no conception of the realities of military life whatsoever. I was not alone in this. Years later, few of us, male or female even the ones who had grown up as army brats had a clear sense of what was about to happen when we entered RMC.

I was one of thirty-two women surrounded by eight hundred male cadets. In my navet, I thought that we would be welcome, now that it was the law to include us. We were not welcome. In reality, the military solution to the quandary presented by the presence of women was to put an end to the farce before it picked up traction. If every female cadet quit or failed out, there could be no further question of our capability to meet the rigorous demands of military college life.

What happened to me happened because I was a woman, and not a quiet woman, not a compliant woman. I figured out quickly that they wanted me to quit. At the time, I didnt understand that knowing something intellectually didnt protect me from its emotional impact or that I was easy prey for doubt and for feeling less valuable than my male peers. It was as if I believed that the men knew more about me than I did and had more right to be there than I did.

And I was blind to the suffering of the other women. I didnt want to look. I heard the rumours from other squadrons: near-naked fourth years parading the recruit hallways wearing only jockstraps, piss being thrown on someone night after night for her comment made to the press, one woman being presented a dildo at a squadron party, a fourth year fondling a womans breasts during intramural water polo and being treated with admiration rather than contempt, French Canadian women being inspected by bullying peers outside of their classroom each morning, and intelligent women being mocked for asking insightful questions in class.

Still, I was desperate to belong to the inner circle of male cadets. I was constantly trying to find out what it would take to fit in. Sometimes I achieved the blissful state of being one of the guys, a garden-variety peer. I basked in those moments, in our teasing, laughter, and roughhousing, enthusiastically joining in when they made fun of me or each other and eagerly roasting myself to show it was okay, so long as I was included.

In the years that followed, it was very difficult for me to overcome my loyalty to RMC and to my squadron. It took four years of breaking down my own resistance and self-doubt as I wrote, four years of overcoming my fear that I wasnt worthy to write my story and had no business telling it. Gradually, paragraph by paragraph, I learned to say things as clearly as I could.

This is a narrative constructed from memory. I have aspired to be rigorously honest, and all the people represented in this work are real, individual people, not composites. I have, however, changed names and identifying characteristics to provide them with as much anonymity as possible. I did not keep a diary during the years depicted in this memoir. Dialogue is as accurate as memory allows, though at times I have combined various conversations for the sake of readability and an economical telling of events. Naturally, there is much I have had to leave out.

My point of view is my own and of necessity, limited. I speak for myself, only about myself and those most directly involved in my experience. The process of transforming living people into players in a narrative was humbling and unavoidably reductive, and for that Im sorry.

dundurn.com

dundurn.com @dundurnpress

@dundurnpress dundurnpress

dundurnpress dundurnpress

dundurnpress