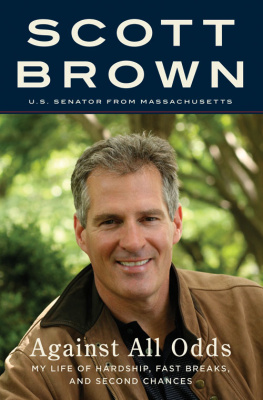

Against All Odds

My Life of Hardship, Fast Breaks, and Second Chances

Scott Brown

Dedication

To Gail, and to Ayla and Arianna,

forever and for everything

Contents

B y the time I turned eighteen, I had movedseventeen times and lived in at least twelve different homes. Most wererental apartments, second-floor walk-ups in slightly sad and dilapidatedconverted houses, where walls had been added and the rooms and floorschopped up one by one.

My bed, when I hadone, was invariably under the hard slope of the eaves. I also made do withcouches and cots, and there was a time when my mother, my sister, and I allslept in the same small room.

When I was twelve,our apartments backyard stood at the edge of a thick tree line and was sodamp and dark that the dirt ground stayed bare all year round. Of the fivehouses I knew, one was a doll-sized rental in the backyard of another homeand the other four belonged to relatives or to whatever man my motherhappened to be married to at the time. We were visitors there; they werenever our own.

At school, I wasoften a free-lunch kid, ravenous for whatever hot food came out of thecafeteria line. Constrained by her choices, good and bad, my mother workedhard, often at multiple jobs, to keep a roof over us, put clothes on ourbacks, and pay babysitters, and she bought food and a few extras withwhatever was left over. I remember days when the largest things we had inour fridge were milk and blocks of yellow government-issuecheese.

My dad was largelygone from my life before I turned one. He materialized only on rareweekends, a smooth talker with his foot on the gas and the convertible topdown. A couple of times when I ran away, he was my destination, but eventhen, I never stayed long.

Looking back, whatsaved me was basketballa game, ironically, that was homegrown, invented inthe Western Massachusetts city of Springfield in 1891 by a YMCA instructorwho was looking for a way to keep his gym class busy during a bout of rain.He started with a peach basket, a soccer ball, and borrowed rules from akids game known as duck on a rock. I doubt Dr. James Naismith could havepictured me, as a kid of twelve, thirteen, or fourteen, riding my bikeseveral miles after a snowstorm with a ball cradled under one arm and a snowshovel clutched in my hand to clear off the courts so I could shoot hoop.Not just for ten minutes, but for hours on end, until my fingers got so numbthat I could no longer feel the ball balanced between them.

What saved me toowere my friends, my teammates, my coaches, and even the cops and a judge,and later the military, although I didnt quite know it all then. I couldhave easily been the kid with the rap sheet and the long record, rather thanthe accolades and the record high scores.

I look back on mylife now, though, and I can honestly say that there isnt one thing I wouldchange: not the arrest, not the violence, not the hunger, not the beatingsand the brute struggles, not even cleaning up someone elses vomit in thestairwell of my dorm at Tufts for $10 in quick cash from the residentadviser because I had no money for extra food. I wouldnt change my decisionto pose for Cosmopolitan magazine, which helped to pay my way through lawschool, forced me to grow up even more quickly, ultimately led me to meet mywife, and also slowly led my father back toward me.

Whatever the widestboundaries are for a Wrentham selectman, a Massachusetts state senator, or aUnited States senator, I am sure that my life lies outside them. But Iwouldnt change any of it, because while it was too often hell as a boyandI myself was at times a hellionthose years and that life made me the man Iam today. I hope, too, they made me a better man.

Busted

T he Liberty Tree Mall was our last stop. It sits right off Route 128 in Danvers, Massachusetts, its big anchor stores rising up flat and square, like stackable Lego blocks. At one end was a Sears with tools and tires, appliances and overalls, and at the other, a Lechmere store, with displays of shiny new luggage, sporting goods, and jewelry, as well as an electronics section and, most important, a record department. We pulled into the lot, away from the hum of highway traffic headed south toward Canton or Braintree, or looping around toward Boston itself. One of my good friends was riding shotgun in the car; one of his buddies was driving. Both were a couple of years older than me and both were basketball players. I was sitting in the backseat. I was thirteen, a few months shy of fourteen, but I was already closing in on five foot eleven. My hair hung long, skimming over my shoulders, drooping into my eyes.

I was lucky in that moment, not lucky that I was along for the dayI had been hanging around these guys for a couple of years, shooting hoop, going to their parties, sipping their beer. That afternoon, I was lucky I wasnt the one driving.

We parked, rolled up the windows, hit the locks of the car, and then shuffled across the baking asphalt. The air was hot, that sticky, humid July heat, where the sky turns thick and white and presses back down upon you until each breath seems liquid, like sucking pool water into your lungs. The weather was why we werent on the basketball court; another reason was that when both guys woke up in the morning, they had decided that they wanted some records. I wanted some too. I had a few records, but all my friends owned dozens and dozens.

We had already been to two record stores that day in another mall, but there was one more inside the sprawling sections of Lechmere, beyond the luggage displays and jewelry counters that beleaguered husbands crowded around when it got close to the holidays. We ambled through the store in the air-conditioned cool, beneath the bright fluorescent lights, which made it impossible to tell afternoon from evening. I had on overalls, blue-and-white railroad stripes with a big front placket. I called them farmer pants, but my mom or I had most likely found these in a surplus store or a discount bin. On top, I wore my junior high basketball jacket, a bright red nylon with a heavy lining for the damp, bleak Massachusetts winters. It had our teams emblem, the Wakefield Warrior, a big Indian chief in profile with a full feather headdress, stamped across the front. If there was a moment when life became premeditated, it was when I got dressed that morning.

We walked into the store and went over to look at the music, arranged alphabetically, A for America, B for Beatles or Bee Gees, C for Creedence Clearwater Revival, D for the Doors. There were the small 45s with one song on either side, but we wanted albums. Although the radios played Elton John, Steely Dan, and the Steve Miller Band, our tastes ran to hard, searing guitar rock, like Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, and Deep Purple, or the pounding, mournful songs of Jim Morrison. Morrisons Riders on the Storm echoed in my mind. I followed, and after they had thumbed through the stacks, I noted what they had chosen, what was cool. My friends headed off to another area of the store, but I stayed behind. After checking around, I leaned in, unfastened the two side buttons on my overalls, and slipped an album behind the jacket. Then another and another, and another after that. I could comfortably carry five. The cellophane covers slid easily against each other, and the thick mass came to rest on my stomach. Trying to look nonchalant, I popped the metal buttons back through their holes, zipped the jacket, and began to amble out of the store. The other guys had already left, and they were waiting for me in the parking lot. I was almost to the doorway; perhaps I was even grinning.

Suddenly a mans hand reached out and patted my back. Instinctively, I stopped and that same man said, Hey, its awfully hot out today. I tilted my head, which was angled down, and looked out through the thick fringe. He was wearing regular street clothes, but still my heart began to pound. Yeah, it is, I managed to reply.

Next page