T his book could not have been completed without the kind assistance of the following, to whom we owe a debt of gratitude:

Tony Tobella, who spent many hours with GARBO translating his experiences from Catalan and Castilian Spanish into English.

Bill Risso-Gill, who allowed us to reproduce his fathers photograph and offered invaluable information concerning his fathers wartime activities as GARBO s first British case officer.

Major General P. R. Kay of the Ministry of Defences D Notice Committee, who gave us his guidance.

Various former members of the wartime Security Service (MI5) and Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) who were directly concerned with GARBO s case. For obvious reasons none can be publicly thanked for their contribution.

L ate in May 1984 a group of retired intelligence officers gathered in the drawing room of the Special Forces Club in London to be reunited with a spy reported dead in 1959. None was certain that the man they hoped to meet would really be the double agent they had known by his wartime code name, GARBO .

GARBO s extraordinary contribution to the Allied victory is well documented. There is hardly a textbook on the subject of strategic deception that fails to mention this remarkable individual . But no author has ever succeeded in penetrating the wall of secrecy that MI5, the British Security Service, constructed around their star performer. His true identity remained as closely guarded in 1984 as it was at the end of the war, when elaborate arrangements were made to protect him for the rest of his life.

My own search for GARBO began in 1972 when I read Sir John Mastermans account of MI5s double agents, The Double Cross System in the War of 19391945 (Yale University Press, 1972), and I was impressed by his observation that GARBO had been something of a genius and had displayed a masterly skill. Indeed, GARBO was the agent singled out for particular praise: Connoisseurs of double-cross have always regarded the GARBO case as the most highly developed example of their art. Unfortunately, Masterman gave only minimal clues as to his true identity, so there was little opportunity to pursue the matter further.

Nevertheless, I was intrigued by the Spaniard known only as GARBO . Why that choice of code name? What had become of him after the war?

According to Sefton Delmer, the veteran journalist who recounted GARBO s adventures in The Counterfeit Spy (Hutchinson, 1973), he set up a prosperous public relations firm along with an import and export business in Angola. But suddenly in 1959 GARBO succumbed to another attack of malaria. And this time it killed him. Or did it? Was it really likely that such an expert in self-preservation would die, ignominiously, running a small business in a corner of Portuguese Africa? I had my doubts, and whenever I tracked down a former wartime MI5 officer I always inquired about GARBO s whereabouts. Unfortunately, GARBO s principal MI5 case officer, Toms Harris, had been killed in a car accident in Majorca in January 1964. His wife Hilda, who had also known GARBO well, had died soon afterwards. Sefton Delmer was also dead, and although his son, Felix, told me that he believed his father had discovered GARBO s real name, he had evidently confided in no one. Nor had he committed it to paper. Even those officers who had spent most of the war supervising double agent operations knew GARBO only by his code name. The need-to-know rule had worked perfectly. All had been aware of GARBO s extraordinary achievements, but none seemed to know his real identity, or what had become of him. It was not until I interviewed Anthony Blunt, in May 1981, that I was at last put on the right track.

Eighteen months earlier the distinguished art historian had been exposed publicly as a former Soviet spy and had been stripped of his knighthood. Apart from attending a short press conference, Blunt had avoided discussing his treachery with anyone. In April 1981, while putting the finishing touches to my history of the Security Service, I had written to him requesting an interview. Blunt had spent five years serving in MI5 during the war and I was anxious to hear his version of events. I knew that even before Blunts exposure he had always refused to talk about his work for the Security Service. His usual excuse had been his fear of the Official Secrets Act. But to my surprise, Blunt had agreed to meet me and invited me to his London flat. Apparently, some of his former colleagues in MI5 had urged him to see me. He imposed only one condition: that our meetings should remain secret until his death, as should certain items of information which he undertook to confide in me.

I knew that Blunt had been a close friend of Tommy Harris and had known something of his collaboration with GARBO . That much was clear from an introduction he had written in 1975 to an exhibition of Harriss art at the Courtauld Institute Galleries. Blunt, who had then recently retired as director of the Courtauld Institute, had offered a brief biography of Harris, and, in doing so, had mentioned his involvement with GARBO :

At the outbreak of war Toms joined the war office, where his intimate knowledge of Spain was of great value. His greatest achievement, however, was as one of the principal organisers of what has been described as the greatest double-cross operation of the war Operation GARBO which seriously misled the Germans about the Allied plans for the invasion of France. After the invasion of France one of the highest commanders said that the GARBO operation was worth an armoured division.

I had a series of lengthy conversations with Blunt during which he recalled his war work and, without prompting, he told me of the single occasion he had dined with GARBO . The two men had been introduced by Tommy Harris in 1944, at Garibaldis Restaurant in Jermyn Street. Blunt still enjoyed a tremendous memory for detail. He even remembered that GARBO had been using the name Juan or Jose Garca. This was no great help as Garca is a very common name in Spain, but nevertheless I felt some progress had been made.

My hunt for GARBO stalled temporarily, but only until March 1984 when I received a fascinating note from a retired British Secret Intelligence Service officer living abroad. He wrote to elaborate on an incident I had mentioned briefly in my history of MI5. I acknowledged his letter and, since I knew he had once served in a wartime counter-intelligence section dealing with Spanish matters, I included my customary query concerning GARBO .

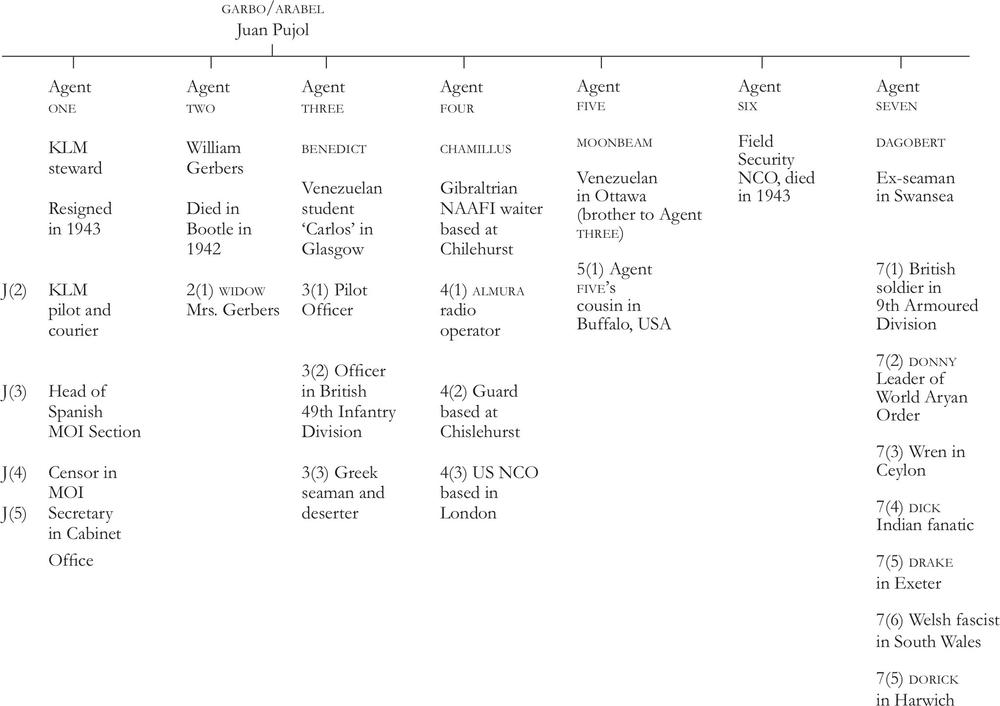

To my delight, the officer replied that he had actually met GARBO and knew his true name. He added that he had no idea whether GARBO was alive or dead, or where he might be located. Dropping everything, I flew to meet my contact and explained what Anthony Blunt had disclosed to me. My new informant told me that GARBO s full name was Juan Pujol Garca and confirmed that he had only used his mothers maiden name, Garca, while in England during the war. Unfortunately, he could shed little light on his possible whereabouts, but suggested Barcelona as a starting point, because the Pujol Garca family had originated from the Catalan capital.

The Barcelona telephone directory contains the names of literally hundreds of Pujol Garcas so, undaunted, I employed a local researcher, Jose Escoriza, to do some detective work for me. He and his family had given me invaluable assistance with my research in the past, and on this occasion he undertook to ring every number listed in the telephone book and ask two short elimination questions, concerning the age and the wartime occupation of every Juan Pujol Garca listed. Was he in his late sixties or early seventies, and had he spent some time in London during the war? A negative to either of these two queries would rule out the candidate. In case of a positive result, I had a longer list of supplementary questions. Had he known someone named Tommy Harris? Had he received a decoration from the British government? Did he recognise the code name GARBO ? Answers to these questions would surely identify the right Juan Pujol Garca. After a week of repetitive calling no result had been achieved, and we had exhausted all the Pujol Garcas with the initial J. But, before going further, my resourceful helper made a significant comment: Every time I call I ask the same question, and I usually get the same response, he explained. But there was one exception. I spoke to one person, who I could tell was too young to be our target, who kept on asking me questions. After so many abortive conversations, this one stands out in my mind as being quite different, but I cant explain how.