New Century Books

P.O. Box 7113

The Woodlands, Tx.

77387-7113

Library of Congress number:

00-192351

ISBN 0-930751-13-2 Hardcover

ISBN 0-930751-14-0 Paperback

ISBN: 978-0-9907181-7-8 Ebook

Copyright 2000 by Thomas Fensch.

All rights rserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

This book was printed in the United States of America.

Ebook formatting by Sun Editing & Book Design, suneditwrite.com

ONCE AGAIN ...

... FOR EVER AND ALWAYS ...

... FOR SHARON

In the New Century Exceptional Lives series:

A Desert Daughters Odyssey:

For All Those Whose Lives

Have Been Touched By Cancer

Personally, Professionally

Or Through a Loved One

Sharon Wanslee

The Man Who Was Dr. Seuss:

The Life and Work of Theodor Geisel

Thomas Fensch

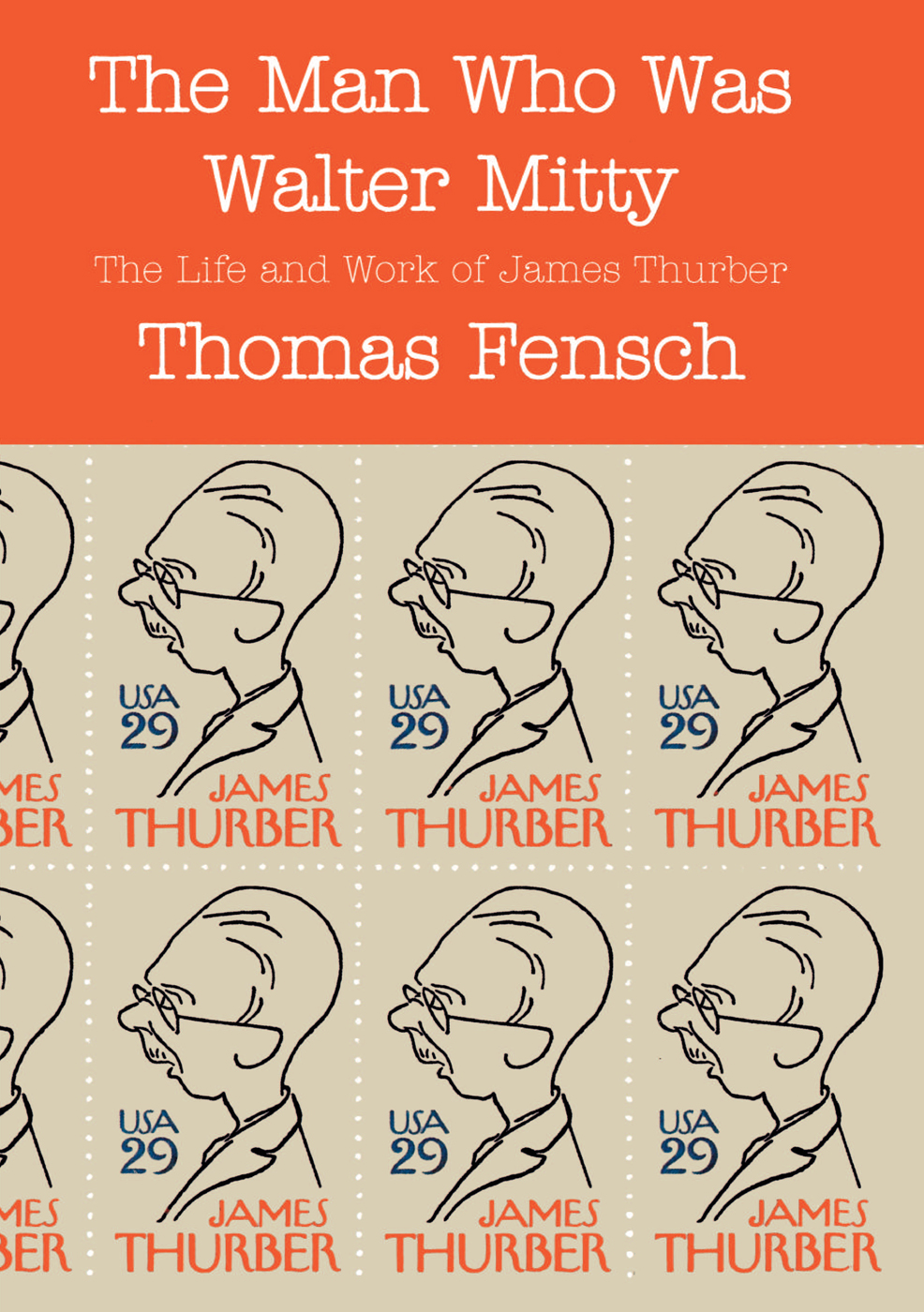

The Man Who Was Walter Mitty:

The Life and Work of James Thurber

Thomas Fensch

Acknowledgments

All the writing by James Thurber are protected by copyright and reprinted here by arrangement with Rosemary A. Thurber and the Barbara Hogenson Agency, Inc. All rights reserved.

Introduction

James Thurber became known

As the Twentieth Century Marks Twain,

and gave us enduring images of men, women and dogs.

When we think about James Thurber, who do we remember?

Images come floating toward us, like aging photographs from a family album:

- He was born in Columbus, Ohio (when it was much smaller, and during a rather idyllic age);

- He was blinded in one eye by a brother during a backyard game of William Tell when he was six. It was the type of childhood accident that left the Thurber family haunted with grief for years, and was an accident that changed Thurbers life forever;

- He was a town boy at Ohio State University, travelling to and from his home and the university by trolley. He matured late, under the guidance of Elliott Nugent. He had problems with Botany (because he couldnt see through a microscope) and with military drill. Since he never passed either Botany nor Military Science, he left Ohio State University without a degree (but much later took his revenge by writing about his experiences at Ohio State);

- His first marriage ended in divorce; but he later remarried happily;

- He began in newspaper journalism and labored on papers in Ohio, in Europe and in New York before finding his true career with The New Yorker;

- He was a self-taught artist with an unmistakable style, which would have been ruined with art lessons;

- His drawings were once described by Dorothy Parker as having the outer semblance of unmade cookies. His style was unmistakable, but few who have ever seen Thurber drawings realize that they were the product of a man lacking one eye and the perspective that full sight would have brought to this work;

- He was exempt from service during World War Two because of his eyesight, but Walter Mitty was used as a password in the armed services in all theaters during the war, as was ta-pocketa, pocketa-pocketa-pocketa from The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which made him enormously proud. Viewing his life in retrospect, Walter Mitty is surely based not only on his own persona, but that of his brothers and father as well;

- He had an early photographic memory of everything he ever read, saw or experienced and when he became completely blind during his middle-aged years, his memory of his past years in Ohio and France and elsewhere saved his sanity (and preserved his career).

His Thurber men (in short story, humor and cartoons) were remarkably timid day-dreaming men; forever harassed, oppressed and conquered by his Thurber women, true harridans all. Only his cartoon dogs, unique variations of bloodhounds or perhaps bassets, looked at life with aplomb and sanity. Thurber once admitted that he had owned, over his lifetime, 70 dogs, surely an exaggeration, but during his boyhood, the Thurber house was never complete without a stray mutt or two (or three or more). And surely there would be no better friend to a half-blind, dreamy, immature boy in a household we can clearly see now as dysfunctional, than a good ol dog. They were his best friends and he was their best friend. He loved dogs, wrote about dogs, drew countless dog cartoons, drawings and doodles ... and years after they were gone, he never forgot their names, smells, habits.

He made the Thurber men, the Thurber women and especially, the Thurber dogs, immortal.

James Thurber was very much like Mark Twain. Samuel Clemens moved far from Hannibal, Missouri, but never forgot his home. Thurber moved from his home in Columbus, to Europe and back to Ohio, then to New York, and eventually life in New England, but generations of his family and his home town of Columbus were never far from his thoughts. One of his most famous quotations was: I am never very far from Ohio and the clocks that strike in my dreams are always the clocks of Columbus.

His dreams, his phenomenal memory and the vague partial cloudy sight he had during his later years gave him a rich source of material, which he mined time and again, working with images, convoluted rhymes, word games and mental puzzles that came into his mind, lodged there and waited for him to retrieve them. He learned the skill of composing a complete short story in his mind, and holding it there until he could dictate it (unreeling it like a tape recording) to a secretary. He could and did memorize 2,000 words (eight pages of text or so) and could dictate them back. It was a skill, he said, that took him ten years to learn.

His heroes were various newspaper journalists he had met during his early years; E.B. White and Harold Ross of The New Yorker, novelist Henry James and Lewis Carroll. It took him years and years to write James out of his system writing like James, writing parodies of James and finally acknowledging his debt to James and moving on. Similarly, Thurber always acknowledged his debt to E.B. White of The New Yorker. White, Thurber said, taught him not just to turn on his prose like water from a tap, but to write with economy, clarity and richness. It was all the difference between hack journalism and the pure craft of writing. Thurber always wanted to write a great American Novel (or said he did). There is some irony in the fact that the prose he is best known for (other than his humorous short pieces) are his nofiction portraits of Harold Ross, White and others at The New Yorker.

Thurbers world is one of confusion, eccentricity and chaos, Thurber scholar Charles S. Holmes, once wrote. Thurbers world is very much like our own enough like our own for us to see ourselves in it but ever-so slightly canted toward impending chaos; one step removed from a pratfall, which would in turn escalate into a riot and near disaster for everyone involved. His short stories, The Night the Bed Fell and The Day the Dam Broke are perfect examples of how Thurbers world can collapse into sheer chaos at the first smallest mis-step. His world is leavened by both humor and tragedy.

This book was written for three reasons: to offer new interpretations of Thurbers work, both text and illustrations; to offer corrections of some mis-interpretations (or factual errors) or Thurber work that I perceive in others and, thirdly, to offer my thanks to Thurber.

As a native of Ohio, I grew up 60 miles north of Thurbers home of Columbus. I read Thurber as I grew up and I remember when he died.