VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

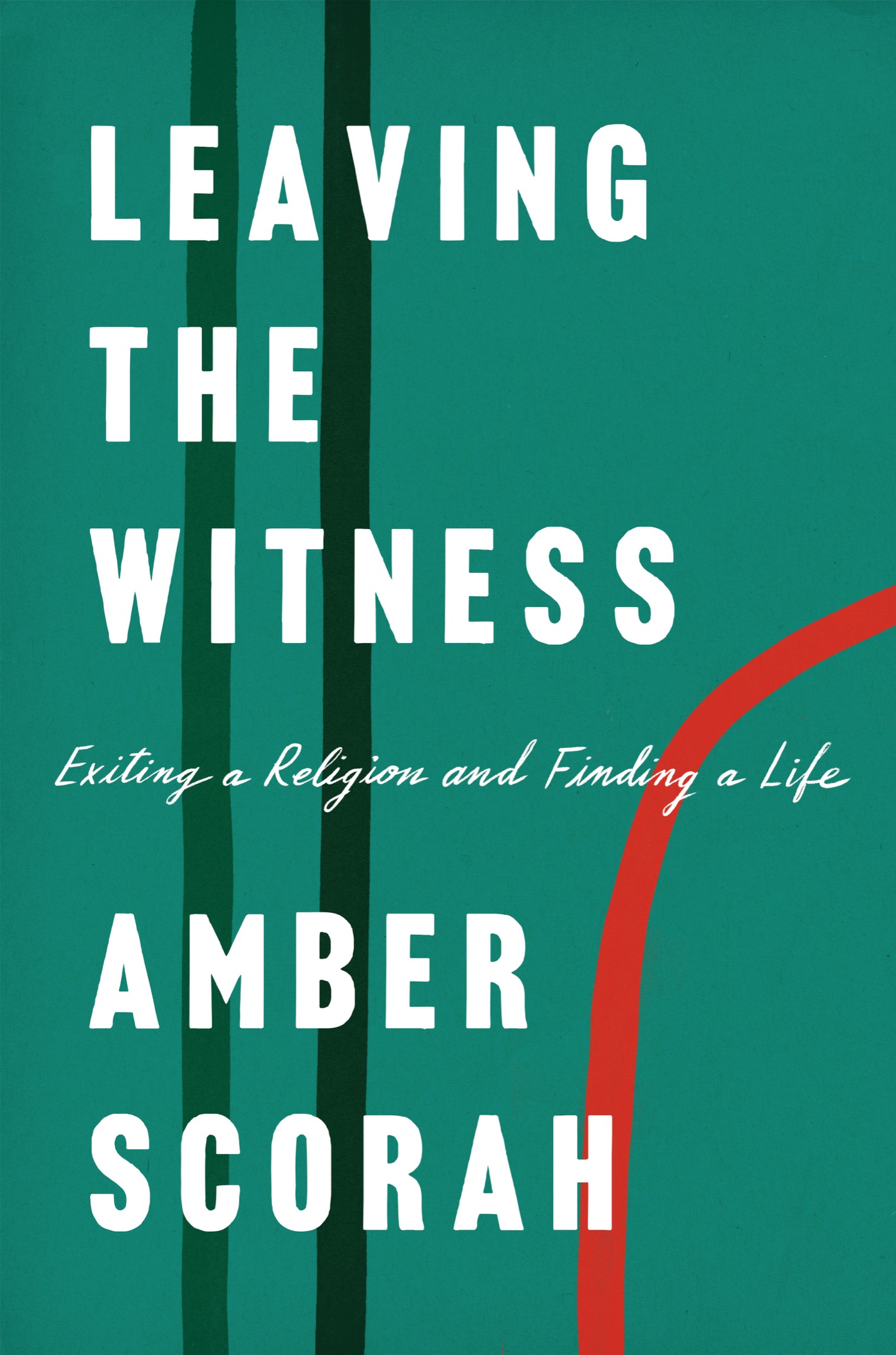

Copyright 2019 by Amber Scorah

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Excerpts from transcripts of Dear Amber podcasts used by permission of ChinesePod LLC.

Excerpts from Mind Control in Twenty Minutes by Patrick Mark Dunlop. Reprinted by permission of the author.

ISBN 9780735222564 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Scorah, Amber, author.

Title: Leaving the witness : exiting a religion and finding a life / Amber Scorah.

Description: New York : Viking, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019003678 | ISBN 9780735222540 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Scorah, Amber. | Jehovahs Witnesses--Missions--China. | Ex-church members--Jehovah's Witnesses--Biography.

Classification: LCC BV4950 .S36 2019 | DDC 289.9/2092 [B] --dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019003678

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Cover design by Na Kim

Author photograph: Lee Towndrow

Version_1

For Karl

The great enemy of the truth is very often not the liedeliberate, contrived, and dishonestbut the mythpersistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.... We enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.

J OHN F . K ENNEDY , Commencement Address at Yale University, delivered June 11, 1962

Its great to be here. Its great to be anywhere.

K EITH R ICHARDS

The first thing I saw when I arrived in Shanghai was a fight on the street. People had extracted themselves from the masses on all sides to watch, standing like awkward party guests. Cyclists held up their black bicycles by the handlebars, pedestrians dallied, their hands full of thin plastic bags from the market. As the momentum of the city pushed against those who were stationary, people spilled over onto the street, like water around rocks. Our taxi driver slowed the car to look.

In the center of the crowd, a man and a woman were arguing. The people who had paused to take in this (as I would come to learn) common spectacle were silent as the parties involved shouted, laying out their dispute. No fist was raisedthough fights on the street were common in Shanghai, at least in those days when tension felt so high, they rarely came to blowsand no intervention was undertaken by the crowd. But the two piqued bodies were electric, their muscles tensed with adrenaline and the faces above them contorted in pent-up anger.

This restraint was more arresting than a punch or shove would have been. A slap of flesh to cheekbone would have provided a moment of relief; a blow would have forced a climax, a gasp, some kind of release, after which the paused city could transform itself back into its loud moving swarm. Bodies would move on, shopping bags would sag to rest on kitchen counters. But this simmering, unrequited tension, it was in the bones of the place. It boiled in arguments on streets, in the alleys of the hutongs sitting stubbornly in the shadows of the developers who waited to bulldoze them, and in the posture of the old men who spat at the ground as a Ferrari passed. It was a pressure that surrounded you and lodged in your head and became your own tension. If ever a place set the stage for a confrontation of any kind, Shanghai did: a theater in which you were occasionally the spectator in the crowd, or, by turns, the person in the middle, fighting.

Things hadnt blown up for me yet, of course. My husband and I had just come in over the Lupu Bridge from the airport, and on the smooth white polyester backseat of a taxi we had been whisked through six lanes of light green taxis and loaded trailer trucks, over shining new bridges full of a thousand years of promise looking down at the slow-moving, ancient brown rivers. Our car was in the old concessions of Shanghai when we came across this scene, creeping among a patchwork of crumbling European architecture bordered by bland high-rise complexes, all skirted by the life and labor that kept twenty million people eating, moving, and surviving in a metropolis that seemed to have no end, and no discernible way out.

For me, there was no excitement like that which could be generated by a move around the world. This was the third time I had done it. Swapping a life in one place for a new life in another created an energy capable of invigorating even people like us, who were tired of living with each other. I had begged my husband to move to China for years. I was not allowed to leave him, so perhaps if I left enough places with him, it would suffice.

And I had longed for China. I had dreamed of being here so audibly and adamantly that the dream drove me into Chinese class and came out of my mouth contorted in the form of sounds like zh, xi, and yunarticulations that made my cheek muscles ache with the effort. My husband wasnt one for dreaming on his own, and he was content where he was, but I yearned for China like a death drive.

In the eyes of all the people I cared about, I ended up just that: dead.

But my goal was not death, it was lifeother peoples lives. I had been trying to save lives seventy hours a month for years as a missionary of sorts (what we called pioneering) in my hometown of Vancouver, Canada, knocking at doors to warn people, people who didnt care, doors that opened (if they opened at all) to disdain, to anger, to apathy, and in the best cases, to a sort of bemused tolerance. I had dedicated my life to save from a fiery Armageddon the inhabitants of my self-satisfied West Coast city, a population of people who cared very little about the impending death they faced.

This unwelcomed work was made easier because I had friends who did it with me, and we went door-to-door, in all weather, drinking Starbucks coffees and noting down who was not at home on our Watchtower-issue lined paper sheets, returning the next week to more closed doors, indulging in an occasional smugness, knowing that they would regret their apathy one day. It was work without pay but done alongside eight million people around the world who were trained week in and week out, and all believed exactly the same things I had been taught as a little girl.

As futile as this work might sound, we had given up any thought of building a life in the world we had been born into, because this world was ending. Soon we would live in paradise, on Earth, and God would bring destruction on those who were not of our faith. It was our duty to save them, or if not save, at least warn them. We were very invested in the trade-off we had made. We gave up any hope of a career, or education, financial security, and certain relationships, all for the sake of saving these people, and goddammitno pun intendedwe were very concerned about their impending destruction. You wanted to save just one of these uppity, self-satisfied people for your trouble. I can use the we and speak with such certitude of a collective of over eight million people because we all believed without a shadow of a doubt that this paradise would soon be ours.