Table of Contents

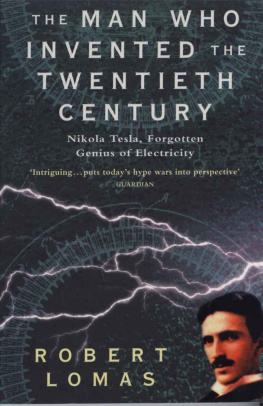

THE MAN WHO INVENTED THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Nikola Tesla, Forgotten Genius of Electricity

By

Robert Lomas

www.robertlomas.com

Dedicated to

Elaine Ann, for her patience, support and encouragement.

Robert Lomas 1999

Robert Lomas has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published 1999 by Headline Book Publishing

ISBN 0 7472 7588 2

This edition by QCS eBooks (2011)

Acknowledgments

I have not written this as a scholarly study because I wanted to write the story of Nikola Tesla in an easy-to-read form. He is a forgotten hero of electrical engineering and deserves to be remembered. I have not inserted footnotes or references to the people who have helped me with information and advice, or the books, magazine and newspapers I have used. I am however extremely grateful to them all.

In particular I would like to thank: Mr Tony Heyes and Drs Michael Hampshire and Robert Tomlinson of Salford University for teaching me about Ohm's Law and how to keep one hand in my pocket. They introduced me to Tesla's work and first kindled my interest in him; the late Dr John Crooks who shared a research lab with me for many years and lived with me through some exciting studies of magnetic resonance effects while still remaining my friend; Mr Gordon Brown, retired Chief Engineer of PIRA, who first put the idea of a biography of Tesla in my head and has been a prolific writer to me on the subject of Tesla's work; Mr Paul Hover who made me realise that Tesla's work deserves to be remembered and brought me up to date on its latest applications; Jenny Finder and her Library Staff at Bradford Management Centre who are always helpful, no matter how unreasonable or vague my request or how out of print the volume I want; my colleagues at Bradford University who have made many helpful comments about Tesla and his work over endless cups of coffee in the Senior Common Room; and finally my agent Bill Hamilton of A.M. Heath and my editor Doug Young of Headline Books, two gentlemen with the rare talent and patience to take the tangled skein of a first draft, find both ends and gently tease out the thread of the story from the knots of my thoughts.

Prologue - Promising Beginnings?

What I had left was beautiful, artistic and fascinating in every way; what I found was machined, rough and unattractive. Is this America? It is a century behind Europe in civilisation.

Nikola Tesla, 1884

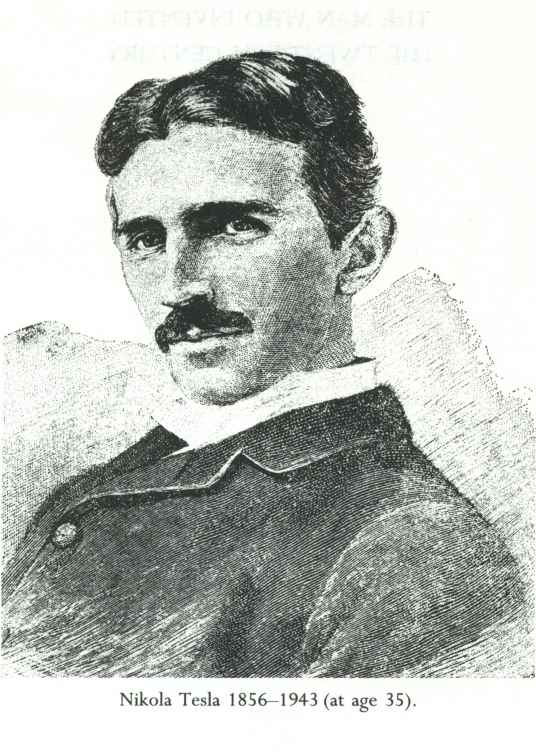

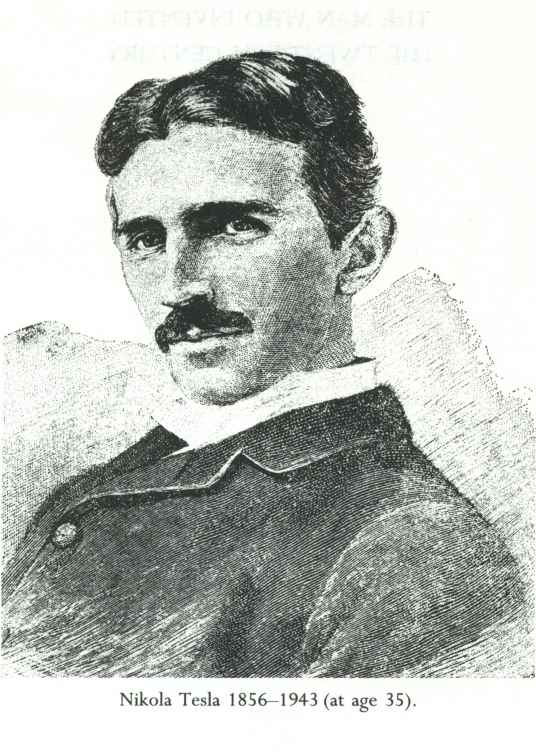

One fine summer morning in 1884, the Calais train was about to leave Paris. Beside it on the platform stood a tall thin young man, with a head of thick black hair parted in the centre. His fashionable moustache only partly hid the nervous movements of his lips as he searched through the pockets of his suit with the urgency of somebody who has lost his wallet. He had, in fact, lost more than his wallet: all his luggage, including his small remaining savings and the ticket to New York he had only just been able to afford, had been stolen. As he realized his plight, he heard a whistle blow, the doors slam shut and he smelled the smoke and steam of the boat-train as it hissed slowly forward.

What was he to do? There was nothing left for him in Paris. He'd sold all his possessions, walked out of his engineering job and abandoned his lodgings. He closed his eyes in despair and, fortunately being blessed with a perfect photographic memory, saw the number of the steamer ticket in his mind's eye. Could he, with this information intact, still get to New York? Surely, he reasoned, the shipping company would have a record of that ticket number and he could claim his berth. As he agonized, the train started to inch slowly forward. If he missed the boat, his chance of getting to the `Land of Golden Promise' would be lost with his belongings.

The decision made, he turned and ran along the platform, using all the length of his thin legs to catch up with and struggle aboard the accelerating train. On the long journey to the coast, he had plenty of time to check his memory for all the details of his missing ticket.

The man with this remarkable memory was a twenty-eight-year-old Serb by the name of Nikola Tesla. We know what happened that day because, in later life, he wrote a series of articles recalling the events of his early life, including the story of his lost luggage.

Simply knowing the number of the ticket, he discovered on reaching the port, was not enough to convince the steam ship company that he should be allowed on board. Taking stock of his situation once again, he searched through his pockets. There were a few coins, a handkerchief, some poems and articles he had written, a neatly tied package of calculations relating to solutions of an unsolvable integral, a rough plan for a novel type of flying machine, and a letter.

The letter was from an English friend with whom he had often played billiards in Paris. This friend, Charles Batchellor, who happened to know the famous American inventor Thomas Edison, had suggested to Tesla that America was the place to make his name as a scientist and had offered to write introducing him to Edison. Tesla had taken more care of this letter than he had of his wallet and luggage. Perhaps now he could use it to help him out of his present difficulty. Carefully opening the letter, he read:

To Mr Thomas Edison Esq... The bearer of this letter is Mr Nikola Tesla...

Here was proof of his identity. He showed the letter to the embarkation officials and, when no other Nikola Tesla arrived to claim the ticket, he was finally allowed up the gangplank.

The crossing was smooth, but Tesla's discomfort can be easily imagined. His meals were provided for and he had a cabin to sleep in, but he had nothing but the clothes he stood up in - not even a change of underclothes. This was a new experience for a fastidious, cultured, highly educated European gentleman. As the days at sea passed, he must have become more and more embarrassed by his unavoidable lack of personal hygiene. So aware was he of his growing personal aroma that he spent much of the voyage sitting at the stern of the boat, hoping that his body odour would be diluted by the sea air. A strong swimmer, he kept his spirits up with the hope that if a millionaire fell overboard, he could rescue him and be rewarded. It didn't happen and, for most of the way across the Atlantic, he continued to sit on deck enduring rather than enjoying the fresh air.

He was on his way to seek work with the world's most famous inventor, an all-conquering and successful entrepreneur who had taken the world by storm. Tesla had first seen the name E-D-I-S-O-N as it was spelled out, letter by glowing letter, on a motor-driven sign above the Edison pavilion at the Berlin Health Exhibition.

Hungry for recognition of his own technical skill and revolutionary ideas, Tesla wanted to tell the famous inventor, who was twenty years older than himself, that the ideas he was carrying in his mind could transform the fledgling electricity industry. His hope was that when he explained his new theory about alternating current to the great scientist, Edison would be eager to fund more research.

A well established electrician, Edison had already invented many marvellous devices that the world was clamouring to buy, including the phonograph - the first record player that played recordings made from wax cylinders - and an electric light, which he had also patented.

Edison, it seemed, was a man who was able to make money from ideas; and he'd seen a chance to get rich from electric lighting when he had realized that people didn't just want to buy a light bulb, they wanted a full electrical system, wanted to replace gas lights with the easier to use electric lights throughout their homes and businesses. At the time, when Edison set out to build an electric lighting system to replace gas, the gas lighting industry of America was worth a fortune, earning about $150 million a year.